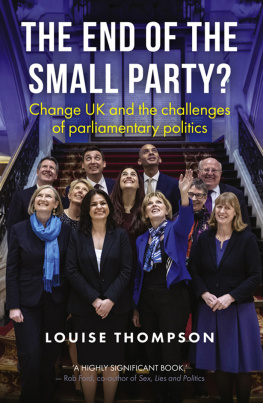

The end of the small party?

The end of the small party?

Change UK and the challenges of parliamentary politics

Louise Thompson

Manchester University Press

Copyright Louise Thompson 2020

The right of Louise Thompson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him/her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN9781526145581hardback

First published 2020

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

COVER IMAGE: Chris J. Ratcliffe, Conservative MPs Resign to Join The Independent Group (Getty Images)

Typeset

by New Best-set Typesetters Ltd

For Percy, Alba and Claudia

I was sitting on a train heading to Cardiff Bay to speak to Plaid Cymru and UKIP Assembly Members on 18 February 2019 when seven Labour MPs held a press conference to announce their departure from the Labour Party and the formation of The Independent Group. Twitter was alive with speculation about what was to happen, and it was good to see that people were, for once, actually talking about small parties in British politics. I was partway through a large research project examining the work of these parties at Westminster and in the devolved legislatures, something I had been fascinated with ever since the election of 56 Scottish National Party (SNP) MPs to the House of Commons in May 2015. As someone who researches and teaches about the UK Parliament it had begun to frustrate me that there was so little information about what goes on beyond the Conservative and Labour benches in the Commons chamber. For too long we seem to have made the mistake of assuming that the smaller political parties who take their seats in the Commons are somehow less worthy of study.

This book draws on over 50 interviews with small party MPs in the House of Commons as well as elected members of the Northern Ireland Assembly, the National Assembly for Wales and the Scottish Parliament. Incorporating The Independent Group/Change UK/The Independent Group for Change has proved to be a challenge. Writing the manuscript in spring and summer of 2019 saw me focusing on a constantly moving target and the 2019 General Election required several chapters to be redrafted. The experiences of these Change UK politicians have, however, on the whole, mirrored those of other new party groups in the Commons and as such the rise and fall of the party acts as a useful case study showing the challenging electoral, political and parliamentary environment in which small parties operate. Some of those whom I have interviewed have expressed concern that I may portray the life of a small party MP as simply too difficult; that by exploring the challenges they face I am implying that they cannot perform the core tasks of being an MP as well as those who sit within larger parties. This is absolutely not the case. The MPs I have interviewed have all demonstrated a deep understanding of House of Commons rules and procedures (perhaps even more so than colleagues from other parties) and have the same strong commitment to representing their constituents as every other MP in the chamber. I'm enormously grateful to all of them and I hope that I have represented their experiences accurately here.

I would like to record here my thanks to Mitya Pearson, who at the time of writing is a PhD student at King's College London, for assisting with some of the interviews and research in relation to the Green Party. Thank you also to my fantastic academic friends and colleagues Cristina Leston-Bandeira, Alexandra Meakin, Alia Middleton and Ben Yong, as well as my husband John for kindly reading drafts of the chapters and for convincing me to write this book in the first place. Emma Crewe was an amazingly thorough reviewer of the manuscript and made the redrafting process which occurred following the events of autumn 2019 a much easier process than it would otherwise have been. Jonathan de Peyer at Manchester University Press provided much encouragement and has kept me on track with his regular emails and conversations about the state of British politics and Jessica Cuthbert-Smith made my manuscript much more fluent during the copy-editing process. Finally, I must thank Alanna Ivin at Rapid Transcriptions, who has never been fazed by my requests for transcriptions of interviews recorded in the hustle and bustle of Portcullis House, train stations and cafs, or from a mobile with intermittent signal. She is an absolute star.

Chapter 1

Three days in February

This marked the end of a turbulent journey for the party's former MPs, who had battled to create and maintain a small political party in a majoritarian political system. The party's impact on the political landscape may have been minor, but its story provides an excellent case study of the electoral and parliamentary difficulties facing small political parties in contemporary British politics.

To understand the story of Change UK and the challenge for small parties more widely we must go back to the morning of Monday 18 February 2019. It was the start of a normal week in contemporary British politics. Edging ever closer to a no-deal Brexit, Prime Minister Theresa May was fighting a continuing struggle with the House of Commons on the one hand, and the European Union on the other, as she sought to pass her Brexit deal through parliament. For several months, parliament and government had been engaged in something of a battle of brinkmanship as MPs tried desperately to regain control of a Brexit which many felt was too harsh, while the Prime Minister tried almost as vigorously to resist attempts to undermine her position and a negotiated deal of which she was overtly proud. All of this was being played out predominantly in the House of Commons chamber, through debates which stretched out into the late evening and seemingly endless rounds of voting on amendments, motions and amendments to motions. MPs were growing increasingly weary of traipsing through the division lobbies and of sitting through debates in which no new avenues were being explored, but things showed no sign of being resolved any time soon.

Though Chuka Umunna was widely seen as the leader of this splinter group, it was Liverpool Wavertree MP Luciana Berger who first took to the podium. She announced the resignation of all seven MPs from the Labour Party in what was a painful but necessary decision.

The question had not been if he should leave the party, but when. It was clear that each MP had their own individual reasons for coming to this decision, but what bound them all together was the shared belief that the Labour Party had changed beyond recognition and was no longer the party which they had previously supported, joined, campaigned for and ultimately been elected under. Their reasons for leaving went even further than this, though. Umunna's broad contention that politics is broken set the tone for the press conference and in many ways summed up the general political and parliamentary mood. In interviews and statements released over the next few days, the MPs went on to express a feeling of frustration not just with the Labour Party and its leadership, but also with traditional party politics, as they did so pressing for some kind of alternative. Just what that alternative was, however, was not yet clear.