2023 Christopher J. Preston

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

The MIT Press would like to thank the anonymous peer reviewers who provided comments on drafts of this book. The generous work of academic experts is essential for establishing the authority and quality of our publications. We acknowledge with gratitude the contributions of these otherwise uncredited readers.

This book was set in Capitolium2 and URW DIN Condensed by the MIT Press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Preston, Christopher J. (Christopher James), 1968-author.

Title: Tenacious beasts : wildlife recoveries that change how we think about animals / Christopher J. Preston.

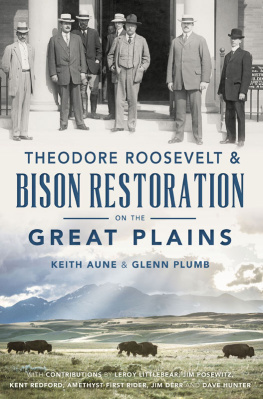

Description: Cambridge, Massachusetts : The MIT Press, [2023] | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Summary: Conventional wisdom is that wild animals are being wiped out. But conventional wisdom skips some important details. Wildlife is rebounding. Not everywhere. Not every species. But a handful of wildlife populations have reached numbers unimaginable in a century. Red deer in Europe, bison in North America, humpback whales in the Atlantic. They have all seen their populations explode. They are back from the brink, numbering in the tens, or even hundreds, of thousands. Their return thrills those who have rooted for their recovery. It terrifies those who grew comfortable without them. This book tracksand tries to understandthese dramatic rebounds. It shines a light on species returning to forests and farms, prairies and oceans, rivers and cities. It asks how these transformations can be happening and what they have to teachProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022011919 (print) | LCCN 2022011920 (ebook) | ISBN 9780262047562 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780262372541 (epub) | ISBN 9780262372558 (pdf)

Subjects: LCSH: Wildlife reintroduction. | Animal populationsEffect of climatic changes on.

Classification: LCC QL 83.4 .P74 2023 (print) | LCC QL 83.4 (ebook) | DDC 639.97dc23/eng/20220524

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022011919

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022011920

10987654321

d_r0

For my father, Robin Preston,

who taught me to love animals

CONTENTS

RESURGENCE

Standing on the dock in the dead of arctic winter, Svein Anders closed his eyes to the northern lights above. All the professor wanted to do right now was listen. As the mountains and green aurora faded from his retina, the sound of a gently rippling ocean washed over his body. Seconds after his mind quieted, he heard the splash of a large object followed by a fierce exhalation of air. Then he heard another. Then another. A fishy scent wafted shoreward. Casting his head back to the sky, Svein Anders's mouth cracked open as he drank in the frigid, nighttime air. He was perched on the doorstep of whales. Dozens and dozens of whales. Humpback and killer whales drawn to Norway's Kaldfjord in the winter months to feast on herring.

The professor lived on the fjord for its cold beauty. Mountains rose in a wall before his kitchen window. Birch trees formed a stubble around his house. Lingonberry flowers speckled the hills in June. The professor built his home with reused materials, spending hours straightening old nails in order not to buy new. He kept chickens and grew potatoes, raised and slaughtered his own sheep. For income, he taught environmental classes at a nearby university and published opinion pieces in the local paper on wind farms, reindeer herding, and the politics of nearby fisheries. His life ebbed and flowed with the seasons.

But the experience on the fjord that night was new. Whales were back in their hundreds, and hisand his neighborsworld was being transformed. The professor felt only elation. But the professor was not the only person having a new experience with wildlife that year.

It was well past midnight when Sue Davies woke to the sound of a sharp hiss beside her bed in an English seaside town. She bolted upright and fumbled for the light switch. An animal ran quickly out the bedroom door. Squinting in the brightness, Davies saw the bedcovers pulled to one side and felt a pain in her leg. She looked down and saw a small patch of skin starting to swell. She put on bedroom slippers and hobbled downstairs. Her shoes were spread across the kitchen floor and the cat flap lay shattered in the mudroom. Davies had been bitten by a fox.

The first thing Davies thought about was rabies. Bats, feral cats, and foxes all carry the deadly disease. She drove hurriedly to Eastbourne General District Hospital to get the bite mark examined, worrying the emergency room staff would think she was mad. A fox in an upstairs bedroom at 2 a.m. sounds absurd. The doctor inspected her leg and carefully cleaned the wound before sending her home with a tetanus shot. As far as rabies was concerned, Davies needn't have worried. The English Channel keeps infected animals out of the United Kingdom.

Davies went home healthy but alarmed. A wild animal wandering through a modern, centrally heated house is a form of heresy. It challenges the barrier between the safe space of home and the wild world beyond. In the uk , where the landscape is gentle and most of the large animals you see are domesticated, a threat to this barrier is almost a full-scale cultural assault.

Davies's experience turns out to be far from unique. A fox bit twin girls Lola and Isabella Koupparis in their upstairs bedroom in Hackney, Central London. Another entered a home in southeast London and grabbed a four-week-old baby off his bed, nearly severing his finger. A third pushed through a kitchen door in Plymouth and bit a seven-month-old sitting in her bouncer in the kitchen.

Nobody knows for sure why foxes are entering so many homes. But one thing nobody disagrees about is this: in the last couple of decades, people are encountering many more foxes in their daily lives. Their pointed faces are everywhere, poking their noses into rubbish bins, darting through hedgerows, and walking jauntily along the tops of garden walls.

Emboldened foxes and fjords full of whales tell us something. Amid a crushing wave of bad news, a handful of wildlife species have bounced back. The recoveries create glimmers of hope and bring complicated challenges. What they show about animals and their tenacity is inspiring. What they demand from minds unaccustomed to their presence is where some of the deepest puzzles lie. We need, in short, a new way to think about animals.

* * *

The news about animals is bleak. Wildlife populations have declined 20 percent over the last century. More than nine hundred species have been wiped off the face of the earth since industrialization. At least a million are threatened with extinction, many of which now number less than a thousand. Vertebrates are particularly hard hit, with populations plummeting over 60 percent since 1970. Birds in North America are down 29 percent. More than 40 percent of amphibians and a third of ocean corals are in danger.

The collapse is almost certain to get worse. Nearly three-quarters of ice-free land and two-thirds of the oceans have been transformed by human activities. Seventy percent of the world's fresh water is devoted to crop and livestock production. Soil is eroding one hundred times faster than it is being built. The signs of human dominance are everywhere. Ninety-six percent of the weight of the world's mammalian life is either human or domestic animals. Let that sink in. People and their livestock weigh twenty-four times all the elephants, whales, and tigers combined.