Barakaldo Books 2020, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

CONFEDERATE CENTENNIAL STUDIES

NUMBER TWENTY

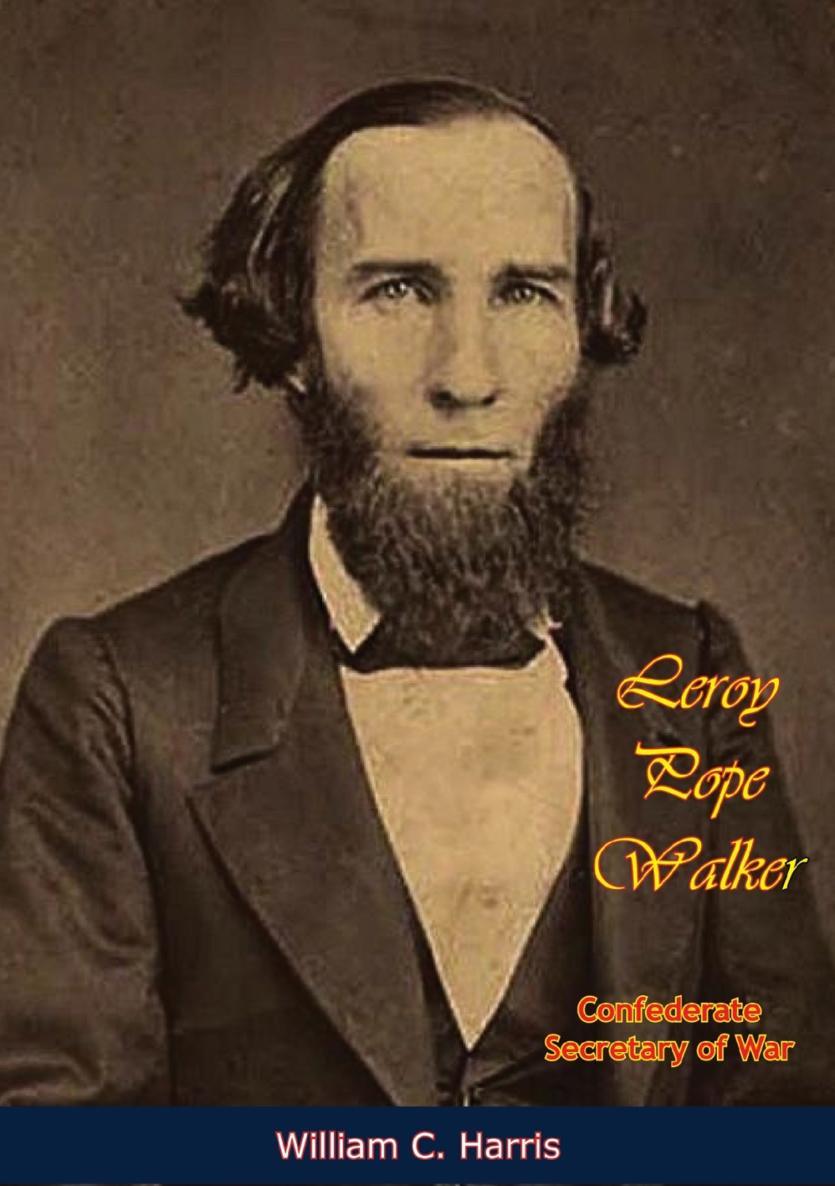

LEROY POPE WALKER

CONFEDERATE SECRETARY OF WAR

BY

WILLIAM C. HARRIS

Foreword

LEROY POPE WALKER, the first Secretary of War of the Confederate States, is probably the least known of the five men who occupied that office. His brief administration of the War Department has long been considered undistinguished. Nevertheless, his accomplishments of organizing the department and placing an army of 200,000 men in the field by September, 1861 reveal that he played a vital role in shaping the military effort of the Confederacy during its formative months. Nor was Walker altogether a man of straw in Jefferson Davis Cabinet, as has been sometimes depicted. Few Confederate leaders were as dedicated and energetic in the performance of their public duties as he was. And I hope that this monograph, although at times unfavorably critical, will bring long-due credit to him as an outstanding figure of the period.

Among the many persons who helped me write this book, I am especially grateful to Dr. Thomas B. Alexander, who read the manuscript with considerable thoroughness and made countless corrections and suggestions. I am also indebted to Mr. David Young, Mr. Henry Marks, and Mr. Wilkins Winn, for their helpful criticisms.

Finally, I tender my thanks to my wife, Betty, for typing the manuscript and for her patience with an abstracted husband.

W.C.H.

Tuscaloosa, Alabama

December, 1961

Prologue: Early Career

WHEN THE Democratic National Convention, meeting in Charleston, April 30, 1860, adopted a platform on slavery in the territories contrary to that supported by William Lowndes Yanceys militant Alabama Platform, Leroy Pope Walker, chairman of the Alabama delegation, dramatically led his twenty-five colleagues off the convention floor. They were followed by the delegations from Mississippi, Louisiana, South Carolina, Florida, and Texas. As one eyewitness declared, ...it was evident that an unprecedented crisis had arrived. The late tumultuous convention was hushed to silence and the stillness of death, while solemnity was depicted upon every countenance.

Although Yancey had long dominated the Southern-rights wing of the Democratic party in Alabama, Leroy Pope Walker was none the less ardent in his support of the Alabama Platform. Indeed, he was described as Yanceys best aide at the Charleston convention, a peerless advocate of state rights, an eloquent spokesman, and a man of strong convictions. In his own words, in Charleston he had been willing to accord anything for the sake of harmony except the surrender of a principle (i.e., the Alabama Platform).

Setting themselves up in a nearby hall, the protesting delegates, who were soon joined by those from Virginia, Florida, Georgia, Arkansas, Missouri, and Delaware, organized themselves into a Constitutional Democratic convention and, with but little delay, adjourned to reassemble in Richmond on June 11. The original convention, unable to nominate a candidate, adjourned to meet in Baltimore on June 18.

At Richmond the Southern Democrats, including Alabama, again led by Walker, endorsed John C. Breckinridge of Kentucky for President and Joseph Lane of Oregon for Vice President. At Baltimore the Northern Democrats chose Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois and Herschel V. Johnson of Georgia as their candidates. The Democratic party was now hopelessly divided.

Leroy Pope Walker and his fellow delegates returned home amid great praisethey had firmly walked out of the Charleston convention in the path of duty and honor...bearing with them the respect and admiration of a nation. {1}

Prior to the crisis of 1860 Leroy Pope Walker had gained considerable renown in his native state of Alabama as an outstanding legislator, a brilliant lawyer, and a staunch advocate of Southern rights. Son of the influential Senator John Williams Walker, of Huntsville, Leroy was reared in a society where the virtues of noblesse oblige were paramount in all aspects of life. He received his formal education at the universities of Alabama and Virginia in preparation for a career in law, and in 1837 was admitted to the bar, before he was twenty-one years old. His initial venture in public office occurred in 1843, when he won a seat from Lawrence County in the Alabama House of Representatives. He first attracted state-wide attention in 1847 at a meeting held to protest the Wilmot Proviso. The resolutions emanating from this conference, which Walker had a major role in formulating, became the basis for the extreme pro-slavery Alabama Platform. {2}

When the state legislature met in December, 1847, the rising young Alabamian was chosen as speaker of the House, a distinction accorded to him again in the 1849-1850 session. In this capacity Walker quickly gained a reputation as one of the ablest legislators to preside over that body. The Democratic newspapers of North Alabama proclaimed his virtues, declaring that he was one of the most promising of the younger men of the Democratic Party. In 1849, and again in 1853, he was a leading candidate for a seat in the United States Senate; however, on both occasions the popular Clement C. Clay, Jr., his home town political rival, was selected by the state Democratic caucus. {3}

While serving in the legislature, Walker tended to represent the interests of his class, the slaveholders, on matters pertaining to the peculiar institution. He labored for the tightening of the state code that would protect the planter whose slaves were subject to sale under the execution of property procedure. He also opposed efforts of the small property owners to increase slave and other property taxes. When the property interests of his class were not clearly involved, however, his policy deviated somewhat from his aristocratic political orientation. He aligned himself decidedly with those in the legislature who supported a greater degree of democracy in the selection of circuit and county (probate) judges. He advocated a reorganization of the judicial department of the state that would create a system of courts whose judges would be elected by the voters. His plan was submitted to the electorate in the form of proposed constitutional amendments, and the provisions passed with little opposition. Walker, furthermore, proposed that the electorate should elect all public officers, and then the responsibility will be where it ought to be. {4}