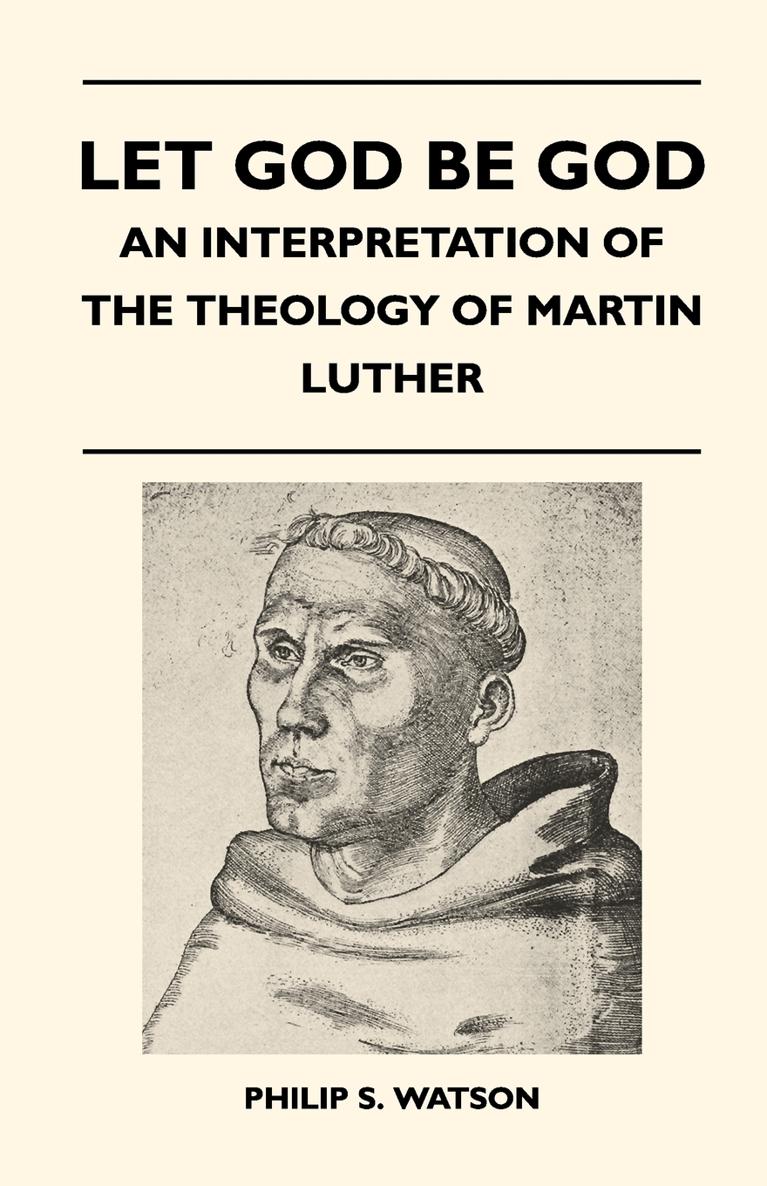

LET GOD BE GOD!

An Interpretation of the Theology of Martin Luther

By

PHILIP S. WATSON, M.A.

Tutor in Systematic Theology and

Philosophy of Religion,

Handsworth College, Birmingham

TO

J. M. W.

WHO GREATLY HELPED

AND

P. J. W.

WHO ONLY SOMETIMES HINDERED

ME IN THE WRITING OF THESE PAGES

PREFACE

IT is now over a quarter of a century since the publication in Germany of Karl Holls epoch-making studies of Luther. They have been followed both on the Continent and more notably in Scandinavia by a veritable Luther renascence. Modern research has led to a new understanding and appreciation of Luther and shown the need for a thorough revision, not only of non-Lutheran, but also of traditional Lutheran conceptions of his reforming work.

The change of outlook has scarcely been noticed in this country, in spite of a marked quickening of interest in the Reformation in recent times. English discussions of Luther still largely reflect the interpretations of Adolf Harnack and Ernst Troeltsch, while English acquaintance with Luther himself all too rarely extends beyond the Wace and Buchheim edition of his Primary Works. This does much to explain the ease with which some eminent Churchmen were lately beguiled by the efforts of a modern Cochlaeus to persuade us that Martin Luther was Hitlers spiritual ancestor. It is particularly unfortunate that Troeltschs Soziallehren, which displays a singular lack of insight in its treatment of Luther, should have found a translator (twenty years after its original publication), whereas we still have no English version of Holls Gesammelte Aufstze, which contains some penetrating criticisms of Troeltsch and is based on far greater knowledge of the sources.

Holl did not say the last word on the subject, of course, nor has it yet been said. If it is ever spoken, it will be due not least to the work of a number of Swedish theologians, to whom the leadership of Lutheran scholarship has passed in recent years. Something of their contribution to this Fernley-Hartley Lecture will be apparent from the Notes at the end of each chapter, but it is fitting here to record a wider indebtedness to them both for personal friendships and for books on subjects other than the Reformation.

It was in Sweden a dozen years ago that I found a Luther in many ways other and greater than I had heard of in either England or Germany; and in this lecture I have tried to show where his greatness essentially lies. An exhaustive account of his theology could not, of course, be given here, but all the main issues have at least been touched upon. I hope to discuss in a further volume several questions that call for fuller treatmentparticularly those of reason, good works and free will.

In this lecture, Luther has been allowed as much as possible to speak for himself. If any error should prove to have crept into the references to his works, it will be remembered that these are not easily available in this country. I have had to rely a good deal on notes taken from them as opportunity has offered, and it has not been possible to make a final verification before going to press. For the translation of passages from the Weimar and Erlangen editions I must bear responsibility; and in quotations from translated sources I have occasionally taken the liberty of modifying spelling, capitalization, and punctuation to conform more nearly to modern English usage.

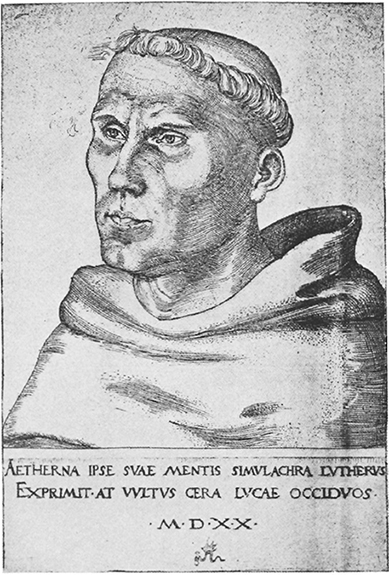

The quotation on page ii comes from The Papacy at Rome (W.M.L., I, 393)Luthers reply in 1520 to the scurrilities of the Franciscan monk Alveld. The frontispiece reproduces an engraving by Lukas Cranach in the same year.

The following pages owe much to the kindness of friends and colleagues. My special thanks are due to Principal Wilbert F. Howard, M.A., D.D., for his unfailing interest and many hours generously given to discussion of the work; to the Reverend Harold S. Darby, M.A., for valuable criticism of the first draft of the manuscript, and the Reverend E. Gordon Rupp, M.A., B.D., for his approval of the second draft; and to the Reverend George W. Anderson, M.A., and the Reverend Michael J. Skinner, M.A., for assistance with the reading of proofs and the compilation of indexes.

PHILIP S. WATSON

HANDSWORTH COLLEGE

Whitsuntide 1947

CONTENTS

ABBREVIATIONS

W.A., Luther, Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe. Vols. Iff. (Weimar, 1883ff.)

E.A., Luther, Smmtliche Werke. 67 vols. (Erlangen, 1826-57.)

Rmerbr., Luthers Vorlesung ber den Rmerbrief, 1515-16. Ed. J. Ficker. 4th edn. (Leipzig, 1930.)

Tischr., Martin Luther, Tischreden. Ed. H. Borcherdt and W. Rehm. (Mnchen, n.d.)

W.M.L., Works of Martin Luther with introductions and notes. 6 vols. (A. J. Holman Company, Philadelphia, 1915-32.)

S.W., Select Works of Martin Luther. Tr. by H. Cole. 4 vols. (London, 1826.)

W.B., Luthers Primary Works. Ed. Wace and Buchheim. (London, 1896.)

Gal. E.T., A Commentary on St. Pauls Epistle to the Galatians, by Martin Luther. Ed. Erasmus Middleton. (London, 1807.)

(Figures in brackets following references to this work indicate chapter and verse on which Luther is commenting.)

B.o.W., The Bondage of the Will, by Martin Luther. Tr. by H. Cole. (Ed. H. Atherton, London, 1931.)

Sermons, Sermons on the most interesting doctrines of the Gospel, by Martin Luther. (London, 1830.)

Letters, The Letters of Martin Luther. Selected and translated by M. A. Currie. (London, 1908.)

M.H.B., The Methodist Hymn-book. (London, 1933.)

S.T., The Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas. Tr. by the Fathers of the English Dominican Province. 2nd and revised edn. (London, 1922.)

(Particulars of other works cited are to be found by reference to the authors names in the list on .)

Part One

The General Character of Luthers Theology

CHAPTER ONE

LUTHER AS A THEOLOGIAN

1. THE TASK OF THE INTERPRETER

A DISTINGUISHED Lutheran Church historian has written of Methodism that it can be described as the Anglican translation of the Evangelical-Lutheran doctrine of salvation. If that is so, the People called Methodists may well be expected to show sympathy and understanding for the genius of Martin Luther, and it is not inappropriate that a Methodist lecture should be devoted to an interpretation of his theology.

The Founders of Methodism were profoundly, if in the main indirectly, influenced by Luthers doctrine. It was with his accents that Spangenberg spoke in Georgia and Peter Bhler in Oxford; and it was his Commentary on the Epistle to the Galatians and his Preface to the Epistle to the Romans that proved decisive in the historic month of May 1738. There is, moreover, a permanent Lutheran contribution to Methodist piety in John Wesleys translations of German hymns, and to Methodist theology in his standard Notes on the New Testament, of which he derived the major portion from the