I

PREFACE

1. ON THE PURPOSE OF THIS VOLUME

2. THREE DISAPPOINTED METHODS OF REFORM

II

3. ON VARIOUS KINDS OF THINKING

4. RATIONALIZING

5. HOW CREATIVE THOUGHT TRANSFORMS THE WORLD

III

6. OUR ANIMAL HERITAGE. THE NATURE OF CIVILIZATION

7. OUR SAVAGE MIND

IV

8. BEGINNING OF CRITICAL THINKING

9. INFLUENCE OF PLATO AND ARISTOTLE

V

10. ORIGIN OF MEDIAEVAL CIVILIZATION

11. OUR MEDIAEVAL INTELLECTUAL INHERITANCE

VI

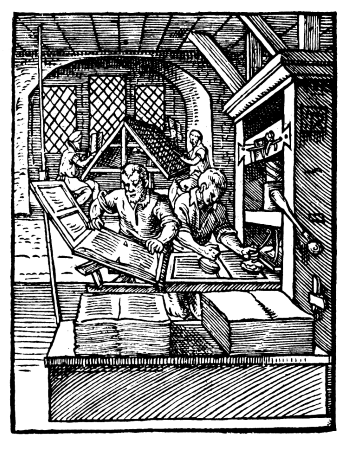

12. THE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

13. HOW SCIENTIFIC KNOWLEDGE HAS THE CONDITIONS OF LIFE

VII

14. "THE SICKNESS OF AN ACQUISITIVE SOCIETY"

15. THE PHILOSOPHY OF SAFETY AND SANITY

VIII

16. SOME REFLECTIONS ON THE PHILOSOPHY OF REPRESSION

17. WHAT OF IT?

APPENDIX

* * * * *

I.

PREFACE

This is an essaynot a treatiseon the most important of all mattersof human concern. Although it has cost its author a great deal morethought and labor than will be apparent, it falls, in his estimation,far below the demands of its implacably urgent theme. Each page couldreadily be expanded into a volume. It suggests but the beginning ofthe beginning now being made to raise men's thinking onto a plainwhich may perhaps enable them to fend off or reduce some of thedangers which lurk on every hand.

J. H. R.

NEW SCHOOL FOR SOCIAL RESEARCH, NEW YORK CITY, August, 1921.

1. ON THE PURPOSE OF THIS VOLUME

Table of Contents

If some magical transformation could be produced in men's ways oflooking at themselves and their fellows, no inconsiderable part of theevils which now afflict society would vanish away or remedy themselvesautomatically. If the majority of influential persons held the opinionsand occupied the point of view that a few rather uninfluential peoplenow do, there would, for instance, be no likelihood of another greatwar; the whole problem of "labor and capital" would be transformed andattenuated; national arrogance, race animosity, political corruption,and inefficiency would all be reduced below the danger point. As an oldStoic proverb has it, men are tormented by the opinions they have ofthings, rather than by the things themselves. This is eminently true ofmany of our worst problems to-day. We have available knowledge andingenuity and material resources to make a far fairer world than thatin which we find ourselves, but various obstacles prevent ourintelligently availing ourselves of them. The object of this book is tosubstantiate this proposition, to exhibit with entire frankness thetremendous difficulties that stand in the way of such a beneficent changeof mind, and to point out as clearly as may be some of the measures to betaken in order to overcome them.

When we contemplate the shocking derangement of human affairs whichnow prevails in most civilized countries, including our own, even thebest minds are puzzled and uncertain in their attempts to grasp thesituation. The world seems to demand a moral and economic regenerationwhich it is dangerous to postpone, but as yet impossible to imagine,let alone direct. The preliminary intellectual regeneration whichwould put our leaders in a position to determine and control thecourse of affairs has not taken place. We have unprecedented conditionsto deal with and novel adjustments to makethere can be no doubt of that.We also have a great stock of scientific knowledge unknown to ourgrandfathers with which to operate. So novel are the conditions, socopious the knowledge, that we must undertake the arduous task ofreconsidering a great part of the opinions about man and his relationsto his fellow-men which have been handed down to us by previousgenerations who lived in far other conditions and possessed far lessinformation about the world and themselves. We have, however, first tocreate an unprecedented attitude of mind to cope with unprecedentedconditions, and to utilize unprecedented knowledge This is thepreliminary, and most difficult, step to be takenfar more difficultthan one would suspect who fails to realize that in order to take it wemust overcome inveterate natural tendencies and artificial habits of longstanding. How are we to put ourselves in a position to come to think ofthings that we not only never thought of before, but are most reluctantto question? In short, how are we to rid ourselves of our fond prejudicesand open our minds?

As a historical student who for a good many years has been especiallyengaged in inquiring how man happens to have the ideas and convictionsabout himself and human relations which now prevail, the writer hasreached the conclusion that history can at least shed a great deal oflight on our present predicaments and confusion. I do not mean byhistory that conventional chronicle of remote and irrelevant eventswhich embittered the youthful years of many of us, but rather a studyof how man has come to be as he is and to believe as he does.

No historian has so far been able to make the whole story very plainor popular, but a number of considerations are obvious enough, and itought not to be impossible some day to popularize them. I venture tothink that if certain seemingly indisputable historical facts weregenerally known and accepted and permitted to play a daily part in ourthought, the world would forthwith become a very different place fromwhat it now is. We could then neither delude ourselves in thesimple-minded way we now do, nor could we take advantage of theprimitive ignorance of others. All our discussions of social,industrial, and political reform would be raised to a higher plane ofinsight and fruitfulness.

In one of those brilliant divagations with which Mr. H. G. Wells iswont to enrich his novels he says:

When the intellectual history of this time comes to be written, nothing, I think, will stand out more strikingly than the empty gulf in quality between the superb and richly fruitful scientific investigations that are going on, and the general thought of other educated sections of the community. I do not mean that scientific men are, as a whole, a class of supermen, dealing with and thinking about everything in a way altogether better than the common run of humanity, but in their field they think and work with an intensity, an integrity, a breadth, boldness, patience, thoroughness, and faithfulnessexcepting only a few artistswhich puts their work out of all comparison with any other human activity. In these particular directions the human mind has achieved a new and higher quality of attitude and gesture, a veracity, a self-detachment, and self-abnegating vigor of criticism that tend to spread out and must ultimately spread out to every other human affair.

No one who is even most superficially acquainted with the achievementsof students of nature during the past few centuries can fail to seethat their thought has been astoundingly effective in constantly addingto our knowledge of the universe, from the hugest nebula to the tiniestatom; moreover, this knowledge has been so applied as to well-nighrevolutionize human affairs, and both the knowledge and its applicationsappear to be no more than hopeful beginnings, with indefinite revelationsahead, if only the same kind of thought be continued in the same patientand scrupulous manner.