And they remained so thereafter. As he feared, the war he took on so reluctantly undermined his dreams for continuing reform at home. And the way he went to war in July 1965using a low-key approach he hoped would preserve his Great Society goalsall but assured a bloody stalemate in Vietnam.

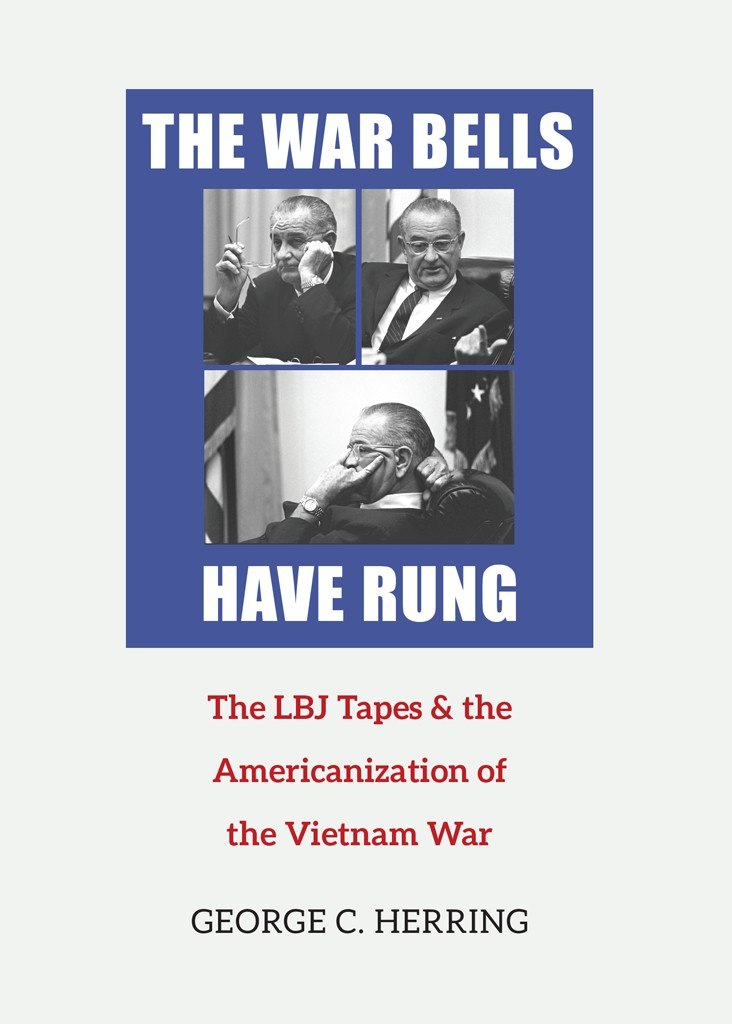

The story of the troop decision has been told often and well. Yet most of this work was done before a remarkableand indispensablesource became available. In the sizable hands of Lyndon Baines Johnson, the telephone became a formidable instrument of presidential power. It was used to extract information from advisers, legislators, and journalists, sell them on programs and policies, cajole and wheedle, and squelch potential opposition. Johnson relied heavily on it. Many of his conversations were taped, and these recordings offer invaluable insights into his moods, thoughts, policy predilections, and modus operandi. This short work draws on records of phone conversations, supplemented by other documents, to explore the crucial events of June and July 1965 leading up to his fateful decision to increase the American troop presence in Vietnam. The phone conversations do not yield any major surprises or challenge conventional wisdom. They do provide an intimate, richly textured portrait of the presidents mental disposition and train of thought during these momentous weeks. They show a chief executive tormented by anxiety, certain of what he must do but profoundly skeptical of success; a seasoned and skillful political operator struggling to build support for policies he himself was uneasy about; and a prickly and thin-skinned leader, obsessed by the press and his rival, New York senator Robert Kennedy, angry with rising criticism but unsure exactly how to counter it. Above all, they reveal a beleaguered chief executive determined to do what he viewed as necessary to protect Americas international prestige by upholding the nations imperiled position in Vietnam, but in a way that would minimize threats to his cherished Great Society programs.

BRANDED a warmonger and baby killer by antiwar extremists and an all too timid and yet much too intrusive commander in chief by Vietnam war hawks, LBJ has enjoyed surprisingly gentle treatment at the hands of scholars. Even writers who deplore the war have given him some benefit of the doubt for taking the nation into it. He inherited a long-standing commitment to and an intractable problem in Vietnam, it is argued. Like his predecessors, he was beholden to the unthinking and virulent anticommunism that gripped U.S. policymakers during the heyday of the Cold War and was trammeled by bloated estimates of the nations global interests and the fears that the loss of South Vietnam, as with the fall of China to the Communists in 1949, would have disastrous political consequences at home. In this context, many writers have insisted that LBJ had little choice but to escalate the war in 196465.the secretive, deceitful way he handled the decision than of what he actually did.

In recent years, scholars have modified and directly challenged this view. Friendly observers insist that LBJs decisions for war were motivated not simply by Cold War exigencies but also by his determination to promote American democratic ideals in places like South Vietnam.

Few would question that by June 1965, Johnson faced an imposing challenge in Vietnam. The Second Indochina War (to become known in the United States as the Vietnam War) had begun in the late 1950s when those Viet Minh who had remained in the South following the 1954 Geneva Conference launched an insurgency in response to South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diems refusal to participate in the elections called for by Geneva and his efforts to forcibly extinguish all opposition to his rule. At first with misgivings, North Vietnam backed the Vietcong rebels by sending men and supplies. JFK responded to the surging revolt in 1961 by significantly expanding U.S. military aid to South Vietnam, increasing the number of military advisers, and secretly authorizing Americans to take part in combat. The overthrow and assassination of Diem in November 1963

Both sides escalated the war in 196465. The overthrow of Diem brought political chaos rather than stability to South Vietnam, coup following coup in what one LBJ adviser called government by turnstile. Buddhists and Catholics fought in the streets of Saigon. Even as North Vietnam prepared regular units to enter the conflict, the South Vietnamese army (ARVN) proved incapable of handling the insurgents. Campaigning for election in his own right in 1964, LBJ responded cautiously. In August, in retaliation for alleged attacks by North Vietnamese gunboats on U.S. Navy ships in the Gulf of Tonkin, he ordered air strikes against North Vietnamese naval installations and secured congressional approval of a blank check authorization to take all necessary measures to repel attacks on U.S. forces and prevent further aggression. Following a one-sided electoral victory, his administration reaffirmed its commitment to preserving an independent, non-Communist South Vietnam and crafted the outlines of a strategy calling for the bombing of North Vietnam and the deployment of additional U.S. forces. Responding to Vietcong attacks on a U.S. base at Pleiku in February 1965, the administration launched air strikes that soon evolved into the sustained, systematic bombing of North Vietnam. This campaign, dubbed Rolling Thunder, aimed to reassure a wobbly Saigon government, limit North Vietnamese infiltration, and demonstrate to Hanoi Americas determination to defend South Vietnam. In early March, the president ordered the landing of 3,500 U.S. Marines at Da Nang to defend U.S. air bases against enemy attack. A month later, he approved the deployment of two additional Marine battalions to Vietnam and agreed to a change of mission from base security to active combat. To avoid interference with the flood of Great Society legislation then moving through Congress, the president kept the mission change secret from all but a handful of top advisers. In response to critics at home and abroad, Johnson in April and May mounted a major peace initiative accompanied by an extended bombing pause.

Despite U.S. escalation, South Vietnam by the summer of 1965 appeared on the verge of collapse. Hanoi flatly rejected U.S. peace proposals and set forth terms unacceptable to Washington. Following a bewildering series of coups and countercoups, a military junta headed by Vice Air Marshal Nguyen Cao Ky and ARVN general Nguyen Van Thieu took power in Saigon. Customarily arrayed in a flight suit with a bright purple scarf and a pearl-handled revolver dangling from his hip, the colorful, mustachioed Ky looked like a character out of a comic opera. His favorable comments about Adolph Hitler provoked consternation in Washington. The Ky-Thieu directorate seemed to all of us the bottom of the barrel, absolutely the bottom of the barrel, a top State Department official later recalled.

In making one of the most important decisions of his presidency, Johnson relied heavily on Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara. On taking office, LBJ had inherited Kennedys advisers and advisory process. Preferring small, intimate gatherings of top officials, he increasingly leaned on McNamara, Secretary of State Dean Rusk, and National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy, collectively labeled by journalists the awesome foursome. Bundy played a key role in the post-Pleiku escalation, but in May the former Harvard dean had committed an