Content

Published in Great Britain in 2016 by Shire

Publications Ltd (part of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc),

PO Box 883, Oxford, OX1 9PL, UK.

PO Box 3985, New York, NY 10185-3985, USA.

E-mail: shire@shirebooks.co.uk

www.shirebooks.co.uk

This electronic edition published in 2016 by Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

Bloomsbury is a registered trademark of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc

2016 John Harrison.

All rights reserved.

You may not copy, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or by any means (including without limitation electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, printing, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

Every attempt has been made by the Publishers to secure the appropriate permissions for materials reproduced in this book. If there has been any oversight we will be happy to rectify the situation and a written submission should be made to the Publishers.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Shire Library no. 802. ISBN-13: 978-0-74781-433-7

PDF e-book ISBN: 978-1-78442-090-1

ePub ISBN: 978-1-78442-089-5

John Harrison has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this book.

Shire Publications supports the Woodland Trust, the UKs leading woodland conservation charity. Between 2014 and 2018 our donations are being spent on their Centenary Woods project in the UK.

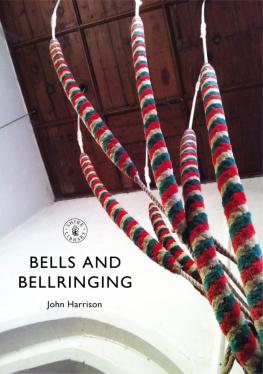

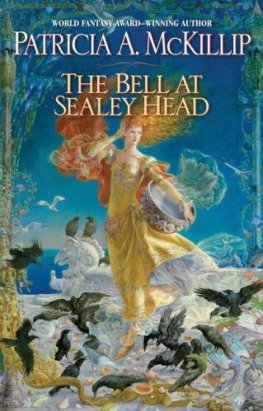

COVER IMAGE

Cover design by Peter Ashley. Front cover: Bell sallies at St Michaels, Steventon, Oxfordshire (photograph by Nick Wright).

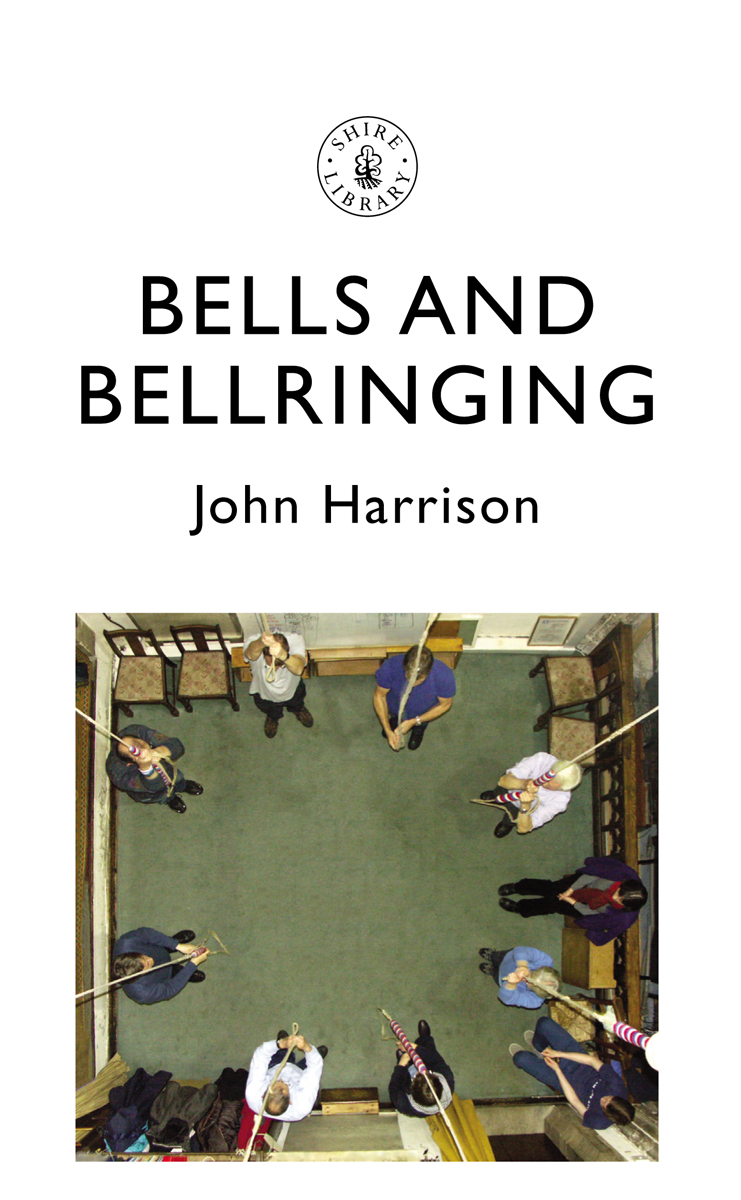

TITLE PAGE IMAGE

Overhead view of a weekly ringing practice at All Saints, Wokingham.

CONTENTS PAGE IMAGE

The masthead of The Ringing World, the ringing communitys weekly newspaper, which has been providing news, views and information about bells, ringers and ringing since 1911, and is the journal of record for performances.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe a debt to the many ringing historians on whose work I have drawn for this book. I would particularly like to thank Chris Pickford whose help and guidance has proved invaluable. Thank you too to the many fellow ringers and others who have so generously allowed me to use their pictures. Finally, thanks to my wife Anne for proofreading the book and to Helen Craig for reading it from the perspective of non-ringing readers for whom it is mainly written. Any remaining defects are of course mine.

Images are acknowledged as follows:

I would like to thank the following for permission for me to use their pictures:

David Beacham, (left). All other pictures are from the authors collection or are in the public domain.

CONTENTS

BELLS AND BELL-HANGING

Bells are the loudest of musical instruments. They are capable of arousing strong emotions and their sound is deeply rooted in many cultures around the world. In England and some other parts of the English-speaking world the unique sound of English-style ringing, especially change ringing, is embedded in the public consciousness. The bells do not play tunes, nor do they strike randomly as they do in many places. They sound in ordered sequences, which continually change to create a captivating soundscape. This unique style of ringing is made possible by the special way the bells are hung, so let us start by looking at how ringing works.

FULL-CIRCLE RINGING

Bells can be fixed mouth down and struck by a hammer or clapper as they are in clocks and carillons (where the clappers are operated from a clavier), or they can be chimed (swung through a small arc with the clapper swinging inside the bell), but English-style ringing is much more dynamic with the bells swinging full circle mouth up to mouth up. The clapper strikes the bell hard at the end of each swing, alternately on each side. Ringing in this way means that the timing can be controlled very accurately. When the bell is swinging nearly full circle, making it swing a little higher makes it swing more slowly and letting it swing less high makes it swing more quickly. This is what makes it easy to ring bells in orderly sequences, and to vary the order continually the essence of change ringing.

The bells of St Magnus the Martyr, London, viewed from above.

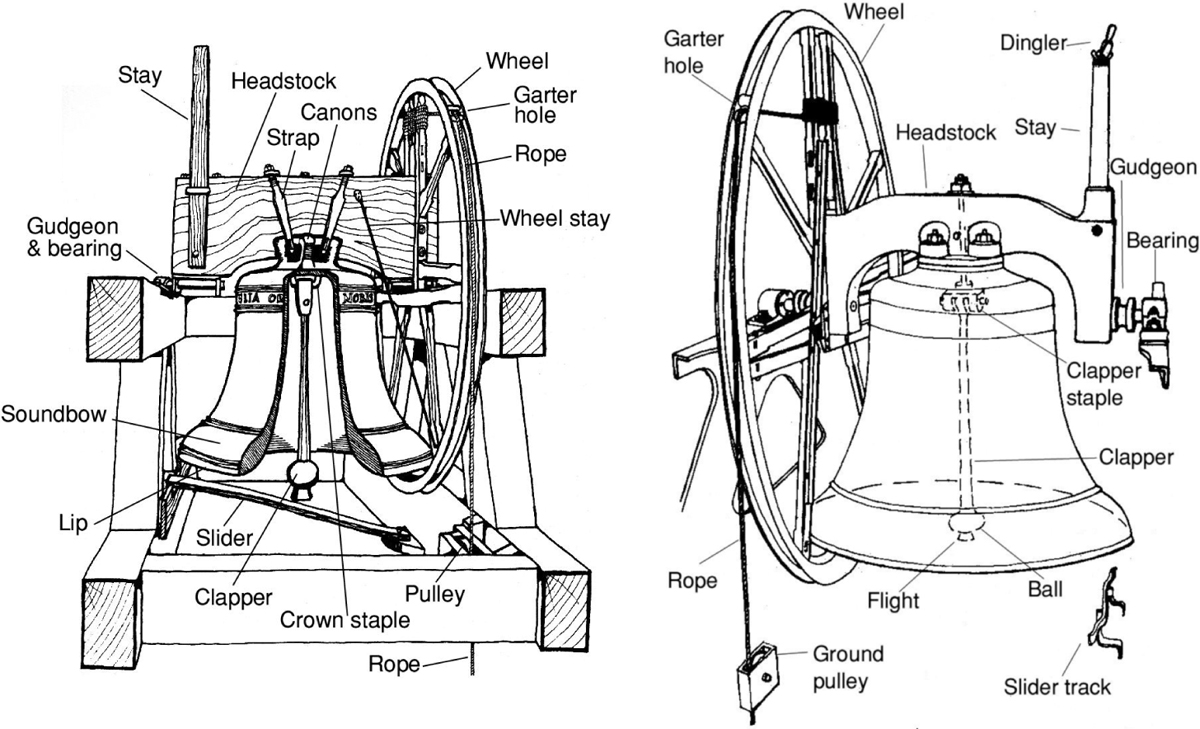

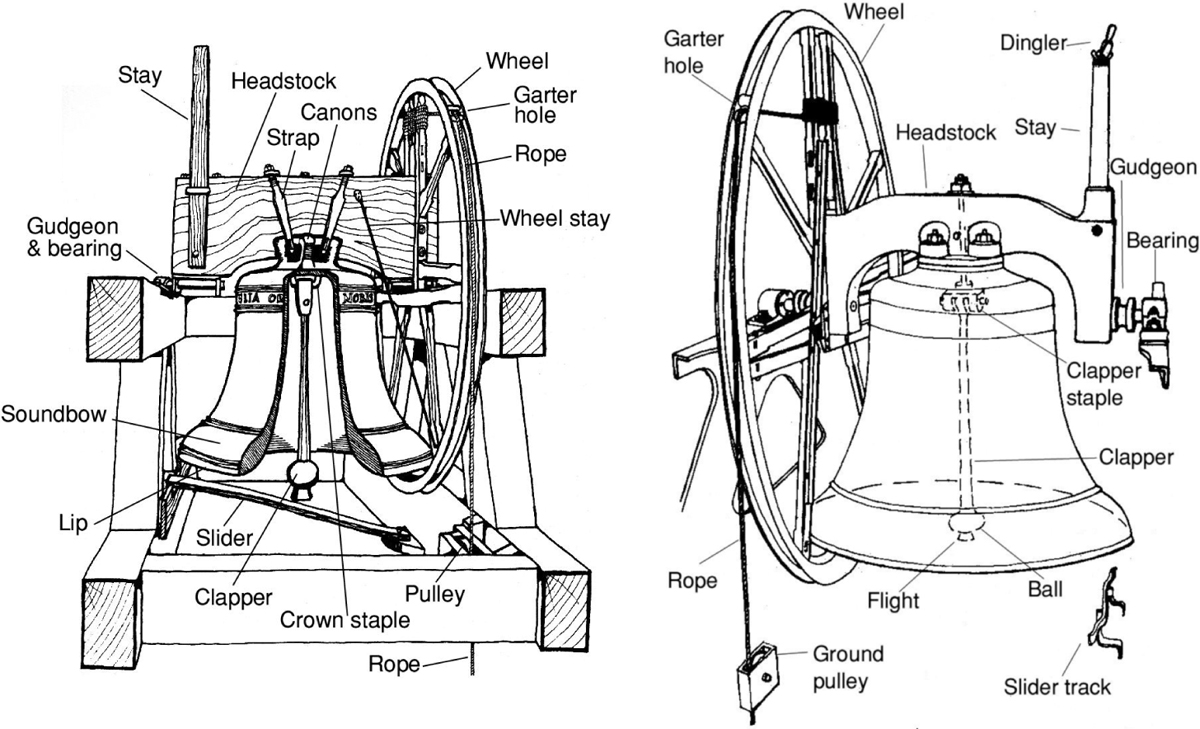

Fig. 1: Bells hung for full-circle ringing with typical fittings: traditional timber headstock (left); modern metal headstock (right).

Each bell is mounted on a headstock with bearings so that it can turn freely. A wheel is attached to the headstock and around it passes the rope that runs down to the ringing room below. Also on the headstock is a stay that allows the bell to rest mouth up just beyond the balance point when it is not being rung.

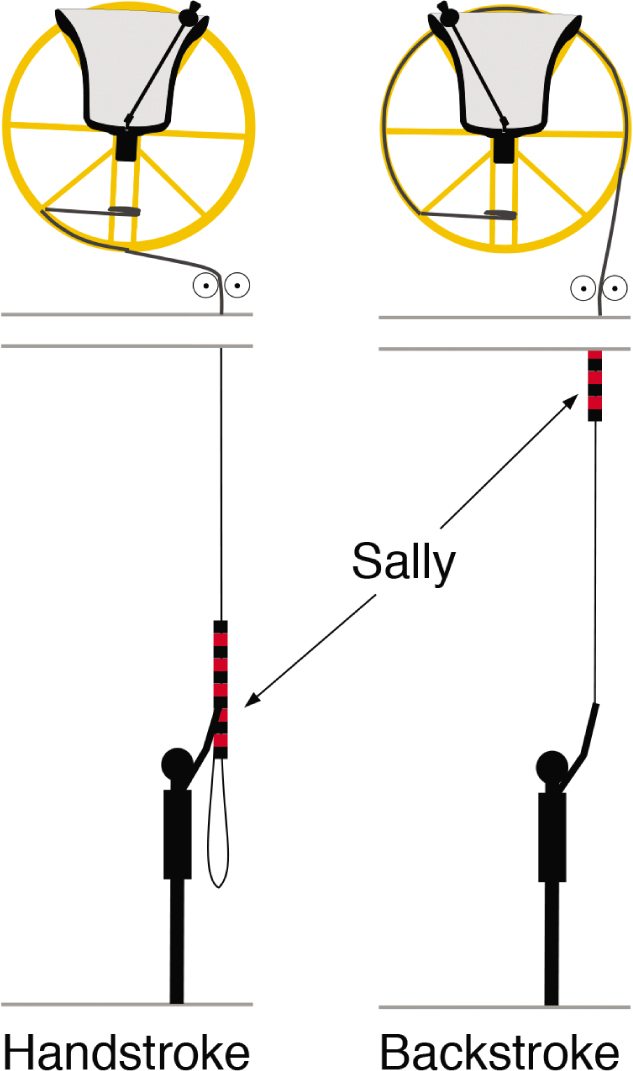

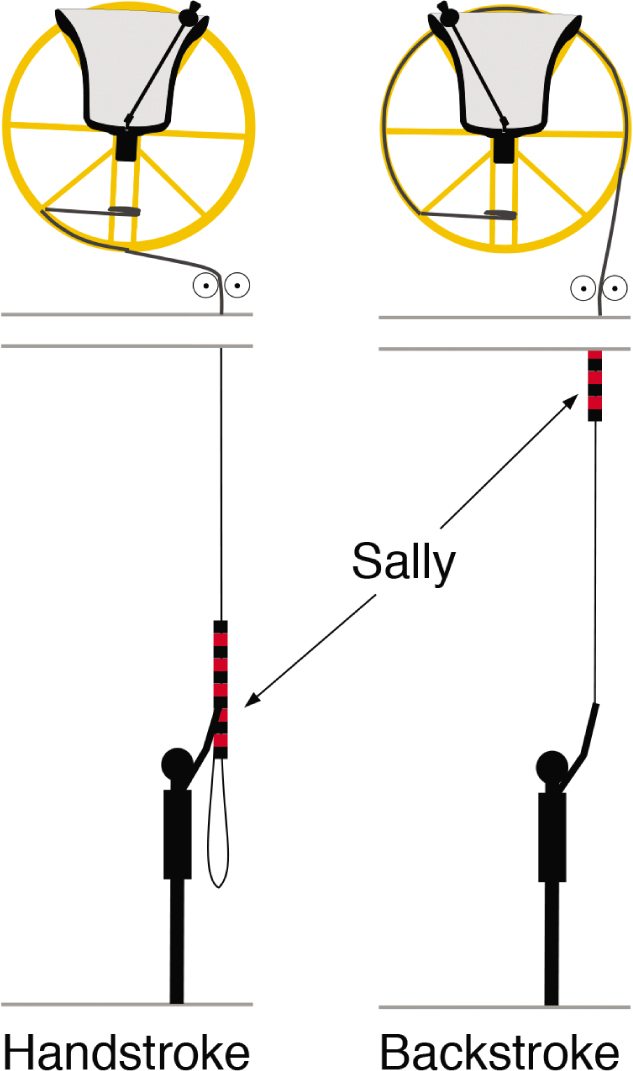

In English-style ringing the rope is the ringers only contact with the bell apart from hearing it. The ringer feels what the bell is doing and judges how far to let the rope rise, and when and how much force to apply to make the bell strike at the right time. The rope winds in opposite ways around the wheel at each end of the swing (backstroke and handstroke). The rope includes a tufted woollen portion, the sally, for the ringer to grip when not holding the tail end (see ).

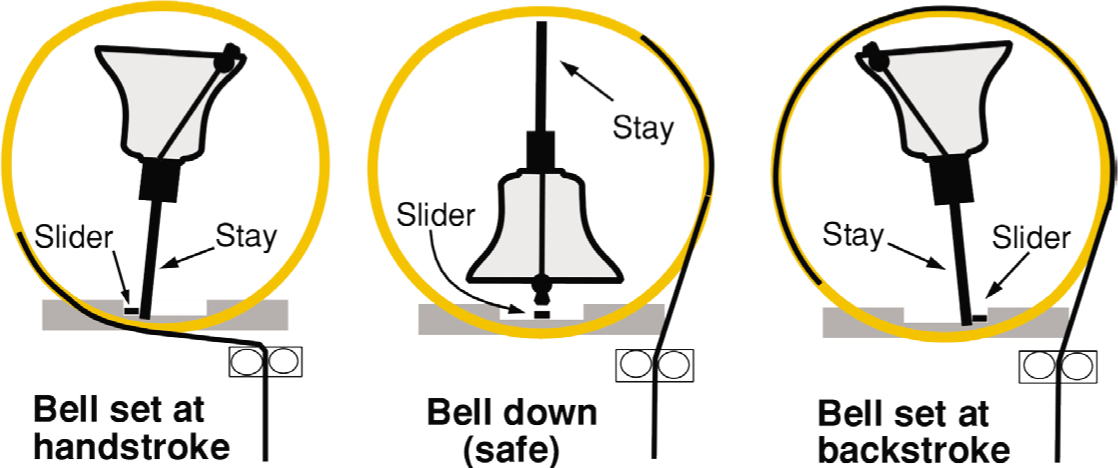

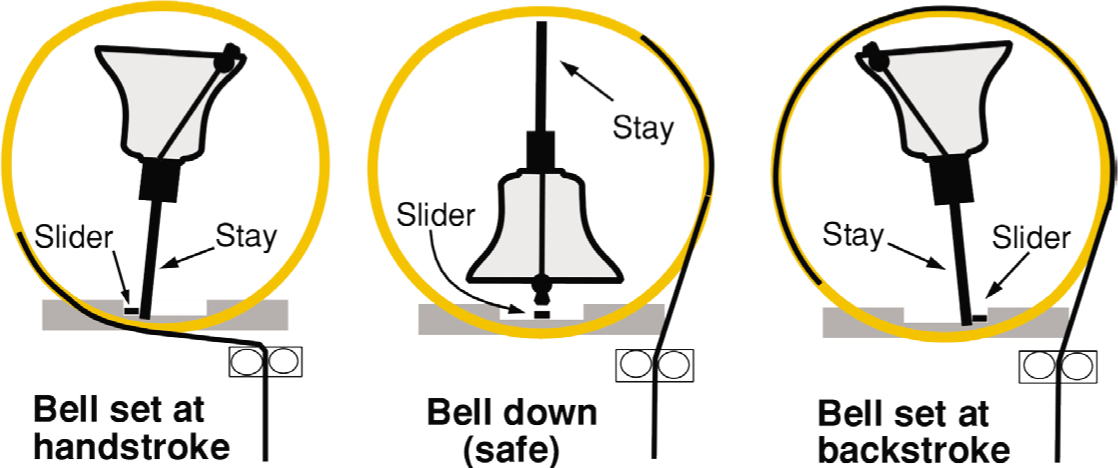

Fig. 2: The position of bell, clapper, stay, slider and rope when the bell is up set at handstroke (left) and set at backstroke (right) compared with when the bell is down (centre).

Fig. 3: The rope wraps a long way over the wheel at backstroke and a short way under the wheel at handstroke, so the ringer holds the rope end at backstroke but at handstroke holds the sally with the spare rope hanging below the hands.

Once a bell is swinging full circle it takes relatively little effort to sustain it. Typical bells weigh between a quarter and three-quarters of a ton some lighter, some much heavier. The number of bells in a ring can vary. Each has a different note in a diatonic scale, with the bells generally getting heavier down the scale and with the ropes falling more or less in a circle, in order. Over five hundred towers have a ringing bell heavier than a ton, with the heaviest (over four tons) at Liverpool Anglican Cathedral. Ringing on heavier rings of bells is generally slower because they naturally turn more slowly.

Raising a bell from the safe mouth-down position to the up position ready for ringing takes significant effort to swing it progressively higher until it is swinging full circle and ready to be set (rested against the stay). Heavy bells take longer and may need more than one person to do this. Such bells are often left up rather than being lowered between sessions.