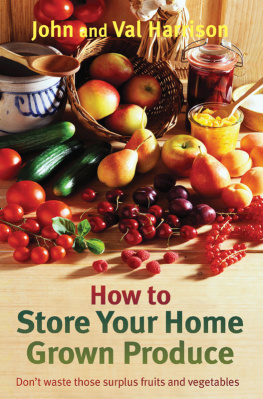

How to

Store Your

Home-Grown

Produce

About the Authors

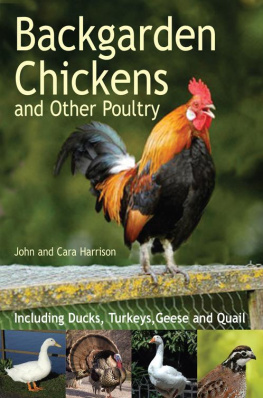

John Harrison, who has been described as Britains greatest allotment authority (Independent on Sunday), lives in the north-west of England with his wife Val.

They aim to be as self-sufficient as they can. John grows fruit and vegetables on two allotments, which provide much of the food they eat.

Val tends to run the kitchen, making her own jams and preserves from the home-grown produce.

This is their second collaboration, following on from Easy Jams, Chutneys and Preserves.

John has written three books on growing your own, including the bestselling Vegetable Growing Month by Month and a book on self-sufficiency Low Cost Living.

Together they run the much-visited website www.allotment.org.uk

Pictures credits: p. 2: the authors / pp. 18, 84, 100, 116, 146, 148: Stephen Liddle / p.98: photo courtesy of A & J Stckli AG ( www.stockliproducts.com ) / Other pictures under Creative Commons License: p.12: scrapygraphics; p.24: Bruno Girin; p.27: ripplestone garden; p.30: pizzodisevo; p.36: Mrs. Gemstone; p.39: Mark F. Levisay; p.42: amiefedora; p.53: Lars Plougmann; p.57: Robert Couse-Baker; p.59: hans s; p.60: ljcybergal; p.64: storebukkebruse; p.66: The Ewan; p.69: Maggie Hoffman; p.70: DRB62; p.71: David Boyle; p.72: Annie Mole; p.78: Tom T; p.81: Zabowski; p.82: Diderot's toe; p85: Simon Blackley; p.88: amandabhslater; p.93: ZioDave; p.94: Sam Catchesides; p.105: fontplaydotcom; p.106: babbagecabbage; p. 109: diongillard; p.119: epSos.de; p.125: chatirygirl; p.128: eek the cat; p.133: Julie Danielle; p. 138: bangli 1; p.139: luvjnx; p.141: sunshinecity; p.152: maesejose; p.157: Stewart; p.159: busbeytheelder; p.165: Michael Gwyther-Jones; p.169: gruntzooki; p.172: Henrique Vicente.

Constable & Robinson Ltd

5556 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published in the UK by Right Way, an imprint of Constable & Robinson, 2010

Copyright John and Val Harrison 2010

The rights of John and Val Harrison to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs & Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A copy of the British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available from the British Library

ISBN: 978-0-7160-2246-6

eISBN: 978-0-7160-2323-4

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Printed and bound in China

Contents

Introduction

O ver the last one hundred years weve seen a revolution in the way our food is produced, how it is stored and distributed and, above all, in our attitudes and relationship with our food.

In many ways this revolution has brought improvements. We are able to go to a shop at any hour of the day or night and buy almost any fresh produce regardless of the season. Ready prepared meals that can be taken from fridge or freezer arrive on the table via the microwave within minutes.

Yet despite this best of all possible worlds more and more people are growing their own food. The reason is, we believe, that people want to be in control of exactly what goes into their food, and not rely on a manufacturer who may add preservatives, colorants and anti-oxidants.

Those fresh strawberries and tomatoes at Christmas no longer amaze us but we realize that however good they may look, they lack the basic quality of flavour. Thats before we even begin to consider food air-miles and the carbon cost of growing out of season.

Whatever the actual reason, the fact is that were growing our own, cutting out all the middle men and carbon costs, and ensuring the quality, safety and flavour of the food we eat.

Growing our own food has created a problem for us though: how do we store the fruits of our labour? When the potatoes are dug up, how should they be kept to last until the day, many months later, when the new potatoes arrive? What should we do with those green beans awaiting harvest when the family cries, Enough for now!

Thats the purpose of this book: to show you the best way to store your produce so you can enjoy your green beans in the depths of winter and keep those potatoes until the new crops arrive.

These are skills that our grandparents and great-grandparents took for granted but have been lost for many of us as our parents felt they no longer needed them and didnt pass them on.

Thats not to say this is a nostalgic, how the Victorians or pioneers did it book. Far from that, its a practical manual firmly based in the twenty-first, not the nineteenth, century. The means to store our food practically and safely are more available and affordable now than ever before.

Perhaps most importantly is the availability of a freezer at an affordable price. We take refrigeration for granted nowadays. Do you know anyone living in a house without a fridge? Yet in living memory home fridges were not all that common and were very expensive to buy.

Of course, there are green issues with freezing. The process uses water and electricity which is the argument against. On the other side of the coin, home-grown produce doesnt attract food miles and that has to more than balance out the equation.

Some of the old methods such as drying foods are now much easier to undertake thanks to modern developments. An electrically powered food dryer can be picked up very cheaply or you can even build a drying cabinet yourself with a little ingenuity and skill.

In a nutshell, we can keep the virtues of growing and storing our own foods with far less effort and a far higher standard of hygiene than that available to our grandparents and their ancestors. This book shows you how to do it.

Measurements and Transatlantic Translation

In writing this, were very aware that it will be published on both sides of the Atlantic. Now George Bernard Shaw famously said that, England and America are two countries separated by a common language. How true!

Weve tried to use both names for the same thing where appropriate, such as rutabaga in the USA but swede in Britain, or eggplant and aubergine. Theres also confusion over the terms bottling and canning. In the UK the term canning would be exclusively applied to sealing the product in metal cans whereas in the USA it is used to describe the process of sealing the food in bottles as well. Basically, if you are American, where you see bottling referred to in the book, please think canning. Another term used in the UK is a Kilner jar. In the US this would be known as a Mason jar or possibly Ball jar. Whatever the name, were talking of the same thing glass canning or bottling jars.

Unfortunately, with measurements its a little more tricky. We tend to use imperial measurements at home pints and gallons, ounces and pounds but our younger readers are happier with litres and grams or kilograms.

To further confuse the issue, a US pint is equivalent to 1.2 pints in the UK, a significant difference. Cups are always a US measurement, by the way, 8 fluid ounces.

Sometimes the difference is negligible, a US fluid ounce is very slightly less than an imperial fluid ounce but a US pint is 16 fluid ounces whilst an imperial pint is 20 fluid ounces or 1.2 US pints.

Next page