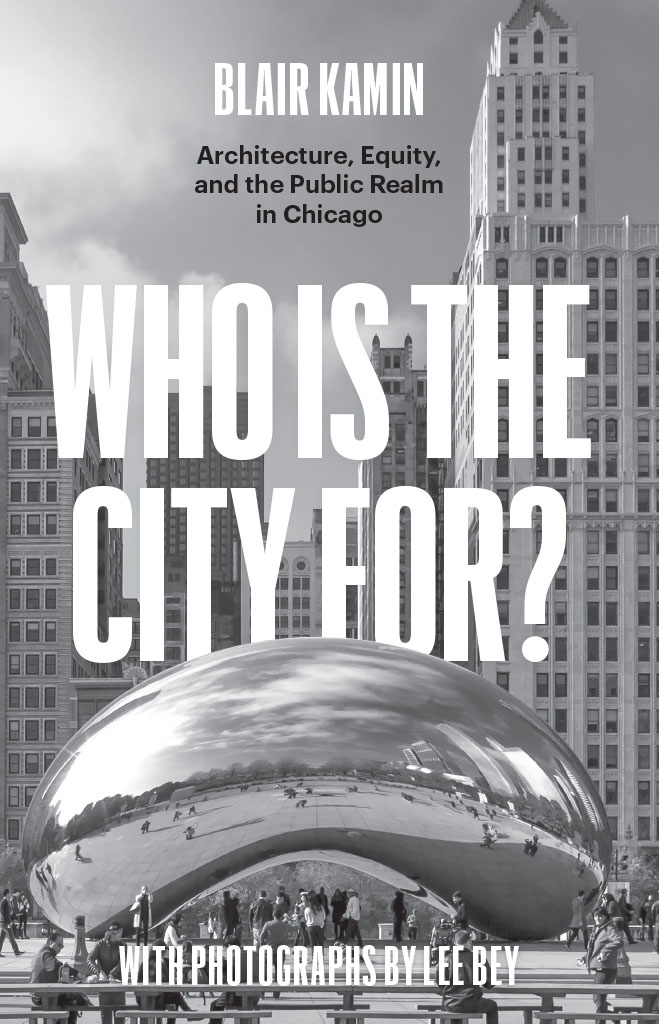

Who Is the City For?

Who Is the City For?

Architecture, Equity, and the Public Realm in Chicago

Blair Kamin

WITH PHOTOGRAPHS BY

Lee Bey

The University of Chicago Press

Chicago and London

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2022 by The University of Chicago

Photographs 2022 by Lee Bey unless otherwise specified

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. For more information, contact the University of Chicago Press, 1427 E. 60th St., Chicago, IL 60637.

Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

31 30 29 28 27 26 25 24 23 22 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-82273-0 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-82287-7 (e-book)

DOI: https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226822877.001.0001

This publication is made possible through support from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation and the Graham Foundation for Advanced Studies in the Fine Arts.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kamin, Blair, author. | Bey, Lee, 1965 photographer.

Title: Who is the city for? : architecture, equity, and the public realm in Chicago / Blair Kamin ; with photographs by Lee Bey.

Description: Chicago : University of Chicago Press, 2022. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022014543 | ISBN 9780226822730 (cloth) | ISBN 9780226822877 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: ArchitectureIllinoisChicago. | City planningIllinoisChicago. | City planningSocial aspectsIllinoisChicago. | Chicago (Ill.)Buildings, structures, etc.

Classification: LCC NA735.C4 K357 2022 | DDC 720.9773/11dc23/eng/20220509

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022014543

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

To Barbara, Will, and Teddy, and in memory of my parents

Contents

Looking back on nearly thirty years of architecture criticism at the Chicago Tribune, I realize that I have borne witness to a dramatic transformation of Chicago, from a declining industrial colossus to a dynamic yet deeply troubled postindustrial powerhouse, whose favored emblem is a jellybean-shaped sculpture of highly polished steel. The mirrorlike surface of that sculpture, officially titled Cloud Gate but widely known as the Bean, reflects the striking skyline of the citys ever-growing downtown, now home to $10 million condominiums, Michelin-starred restaurants, and an elegant promenade that rims the once badly polluted Chicago River. But the Bean does not reflect the reality of a very different Chicago. That Chicago, though not without distinguished buildings and untapped economic potential, is also a place of weed-strewn vacant lots, empty storefronts, and unceasing gun violence. Indeed, Cloud Gate may be the ultimate shiny, distracting object. While the 2020 census revealed that Chicagos population grew by nearly 2 percent during the previous decade, to 2.7 million, the dramatic disconnect between the two Chicagos prompts the question: Is this a good city, a just city? Absolutely not. Which prompts a second query: Can those responsible for building the city advance the fortunes of neighborhoods devastated by decades of discrimination, disinvestment, and deindustrialization? On that crucial matter, the jury is still out.

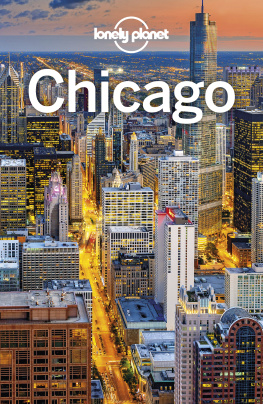

Cloud Gate sculpture in Millennium Park: Is the new icon of Chicago also the ultimate shiny, distracting object? Photo by Lee Bey.

This book, my third collection of Tribune columns published by the University of Chicago Press, is loosely framed around a central issue of our time: equity. What can architecture, traditionally the province of the rich and powerful, do to make cities like Chicago more equitable, serving poor, working-, and middle-class people, not just the 1 percent? A related question can be asked of the fields of transportation and urban planning, which in the wrong hands have led to such notorious projects as freeways that divide Black neighborhoods from white ones or sever one part of an impoverished neighborhood from another. The question applies, too, to the field of historic preservation. Whose history gets remembered and whose history is erased, either by bulldozers or by willful ignorance?

In short, who is the city for?

Let me start by clarifying that I take equity to mean fairness or justice in the way people are treated rather than the terms economic meaningsa share of stock or the value of a piece of property after debts are subtracted. This emphasis on fairness has significant implications for architecture and the built environment. One side of town shouldnt have bigger, more amenity-packed parks than the other just because its inhabited by the wealthy. If anything, the poor parts of a city should have the prime parks, because their residents live in far worse conditions than the rich.

That was among the essential points of my 1998 series of articles examining the problems and promise of Chicagos greatest public space, its nearly thirty miles of beaches, harbors, and parkland along Lake Michigan. The series, Reinventing the Lakefront, documented a shameful disparity in acreage, access, and amenities between shoreline parks bordered by mostly white, affluent neighborhoods on the citys North Side and those lined by largely Black, poor neighborhoods on the South Side. Since then, city agencies and the Chicago Park District have spent hundreds of millions of dollars on the south lakefront, including architecturally ambitious pedestrian bridges and a harbor and marina that welcome parkgoers as well as boats. But any discussion of equity, I argue, should not be limited to apportioning resources fairly or controlling soaring rents.

A wiser alternative, in my view, is to expand and enrich the social meaning of equity by borrowing from its economic counterpart, so that, when we use the word, were talking about the physical environment that we share. Shared spaces encompass all aspects of the public realm, from sidewalks and streets to transit stations, to public libraries and public housing. Private buildings, be they skyscrapers, flagship stores, or museums, do just as much as, if not more than, public ones to shape the public realm. At best, the public realm can serve as an equalizing force, a democratizing force. It can spread lifes pleasures and confer dignity, irrespective of a persons race, income, creed, or gender. Shared space suggests shared destiny. Or, to put matters in terms of hard-nosed self-interest rather than empathetic generosity, the recognition that cities are shared venturesand that the fate of one section of the city is inseparable from anotherrepresents a far more viable long-term strategy than its opposite: containment of the poor, whether in ghettos, public-housing projects, or dysfunctional neighborhoods.

The shootings and thefts that have spread from Chicagos South and West Sides to the downtown and affluent North Side neighborhoods like Lincoln Park make clear the costs of failing to address the root causes of long-festering problems associated with high concentrations of poverty. No neighborhood is an island, as the shattered glass of North Michigan Avenue storefronts hit by smash-and-grab thieves and the fatal May 2022 shooting of a teenager in Millennium Park near the Bean reveal.

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI / NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).