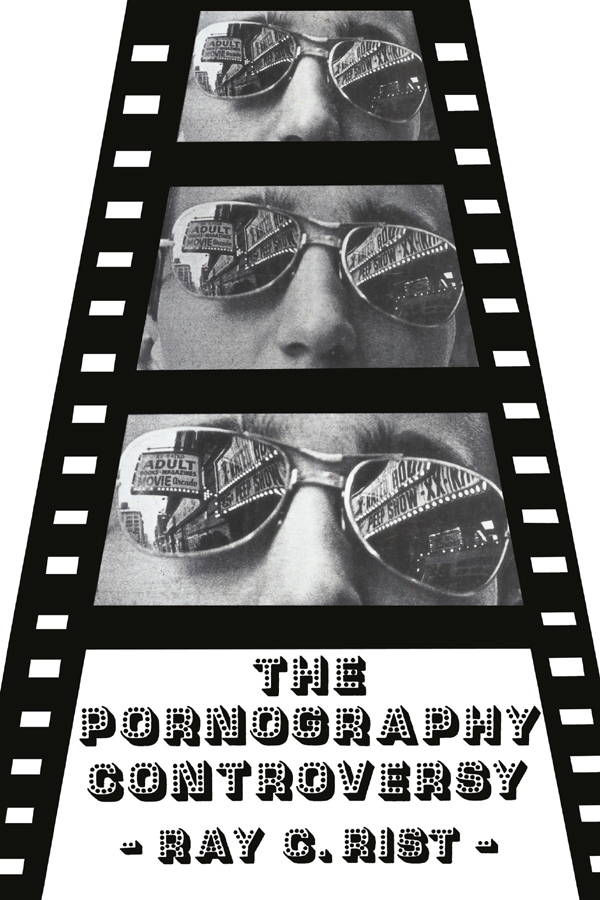

First published 1975 by Transaction Books

Published 2019 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1975 by Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Catalog Number: 73-92813

ISBN 13: 978-0-87855-587-1 (pbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-53766-8 (hbk)

The United States is a complex and highly heterogeneous society. It is faced with such paramount issues as racism, poverty, environmental pollution, the nuclear arms race, corruption of government, and the decline of democratic institutions. Is it not then paradoxical that so much attention and energy is spent discussing and debating what to do about pornography? Considering the other problems that confront us, a discussion of action related to sexually explicit material may seem a frivolous luxury that American society can ill afford at this time. Those addressing themselves to saving the eco-system (and the human species) or those working for a new and more humane political system can rightly ask why even the most extreme sexual material should compete as an imminent social problem for the attention of citizens.

Objectively, of course, sexual material does not in any way compare with these conditions. Pornography is no more than a pseudo problem when any attempt is made, for example, to evaluate it in light of the possibility of nuclear warfare. Yet for many, the presence of pornography in American society is viewed as a threat to the moral standards of the country or as an omen of the decay and decline in the moral fabric of the society. The concern is sometimes expressed as follows: If the moral climate of the country is polluted with pornography, it wont make any difference what the air is like. A polarity of views emerge when debating whether pornography constitutes a legitimate social problem. Those who express concern about such material hold the view that issues of public morality take precedence over issues related to objective social conditions. Others argue that the material conditions of the society are more important than any attempt to formulate public moral standards. Such opposing views often give evidence of differing perspectives on the appropriate role of the state and the means by which this civil society should be governed.

Were pornography amenable to empirical analysiscould it be analyzed, evaluated or measured for irrefutable conclusions as to its goodness or badness, its corruption or edification, its short- and long-term effects on human values and behaviorthen there would be data upon which many of the present debates and dilemmas could be resolvedassuming all parties involved were agreeable to base conclusions on research findings. But sexual material does not appear to be accurately evaluated by measures now available; we have been, heretofore, unable to create measures of values which are themselves value free. In other words, the very criteria by which one would wish to evaluate pornography, its goodness or badness, are in themselves subjectively determined and represent normative decisions on the part of those defining the terms.

The current controversy over the presence of pornography in American society occurs simultaneously on two levels: one philosophical or theoretical; the other pragmatic or operational. The philosophical issues relate to notions of morality, to the parameters of civil democracy and to the rights of the individual as a member of both society and the state. The pragmatic or operational concerns are: enactment of law, the use of coercion to contain certain forms of cultural expression and defining what, in fact, constitutes pornography.

The essays in this volume address themselves to these two levels of the controversy. It should be evident that there is no consensus among the authors represented. Opposing points of view are presented with respect to theoretical as well as operational concerns. In this conection, one will find a myriad of views on what would constitute the good society as well as the good state.

The fact that there is no single proper posture toward either morality or law means both the individual and the collectivity must continually scrutinize their operational positions as well as their theoretical assumptions. To assume an absoluteeither with respect to what constitutes pornography or what to do about itis to assume a static society, and, as we suggest in our subtitle, Changing Moral Standards in American Life, social change in America is alive and well.

January 1974

Portland, Oregon

Ray C. Rist

In American society, the use of law has become a major, if not the exclusive, instrument for the amelioration of what are believed to be pressing social problems.1 With incessant and escalating pressures to do something, the passage of legislation provides both the politician with a visible demonstration of his concern and his constituents with reassurance that something is indeed being done to resolve the problem.2 Mandatory automobile-emission inspections, the hiring of women and minorities for other than their traditionally segregated and low-paying jobs, the banning of the pesticide DDT, and the refusal of cities to allow theaters to show live sexual acts are but a few of the situations in which behavior is being compelled or prohibited by law in response to a perceived problem. In the end, the law is being used to coerce people into being virtuous.

But things are not always as they appear. The passage of legislation does not necessarily imply the existence within a community of a consensus as to what precisely constitutes the problem, or how most effectively to resolve it. On the contrary, there may be significant disagreement on the issue and the resultant law may be only the reflections of one segment of the population who were able to transform their particular position into law.3 Using law to impose virtue implies a conception of what behavior is believed to be virtuous or moral or proper. When law is used in this manner, it becomes a means of expressing the views of those who have the power to define the terms and have these terms become the ones on which the problem is approached. Though the reliance on law to respond to social problems in this society has taken on an aura of being both inevitable and desirable, it need not be either. Further, the attempt to solve problems through the instrumentality of law may not diminish the magnitude of the situation, but in fact enhance it. Thus the law comes to be placed in the paradoxical position of reinforcing what it theoretically intended to eradicate.