ABOUT THE BOOK

There is a common misconception that to practice Zen is to practice meditation and nothing else. In truth, traditionally, the practice of meditation goes hand-in-hand with moral conduct. In Invoking Reality, John Daido Loori, one of the leading Zen teachers in America today, presents and explains the ethical precepts of Zen as essential aspects of Zen training and development.

The Buddhist teachings on moralitythe preceptspredate Zen, going all the way back to the Buddha himself. They describe, in essence, how a buddha, or awakened person, lives his or her life in the world.

Loori provides a modern interpretation of the precepts and discusses the ethical significance of these vows as guidelines for living. Zen is a practice that takes place within the world, he says, based on moral and ethical teachings that have been handed down from generation to generation. In his view, the Buddhist precepts form one of the most vital areas of spiritual practice.

JOHN DAIDO LOORI (19312009) was one of the Wests leading Zen masters. He was the founder and spiritual leader of the Mountains and Rivers Order and abbot of Zen Mountain Monastery. His work has been most noted for its unique adaptation of traditional Asian Buddhism into an American context, particularly with regard to the arts, the environment, social action, and the use of modern media as a vehicle of spiritual training and social change. Loori was an award-winning photographer and videographer. His art and wildlife photography formed the core of a unique teaching program that integrated art and wilderness training by cultivating a deep appreciation of the relationship of Zen to our natural environment. He was a dharma heir of the influential Japanese Zen master Taizan Maezumi Roshi and he authored many books.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

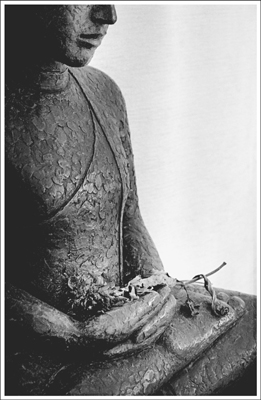

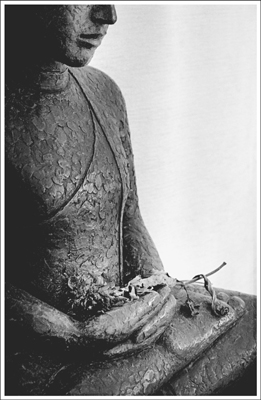

Photo by Robert Aichinger

Invoking Reality

Moral and Ethical Teachings of Zen

JOHN DAIDO LOORI

Shambhala

Boston & London

2012

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1998 by Dharma Communications

Cover design: Graciela Galup

Cover photograph: Michael Wood

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Loori, John Daido.

Invoking reality: moral and ethical teachings of Zen / John Daido Loori.

p. cm.

Originally published: Boston: Dharma Communications, 1998.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2450-8

ISBN 978-1-59030-459-4 (pbk.: alk. paper)

1. Religious lifeZen Buddhism. 2. Zen BuddhismDiscipline. 3. Buddhist ethics. I. Title.

BQ9286.L664 2007

294.35dc22

2006052314

Contents

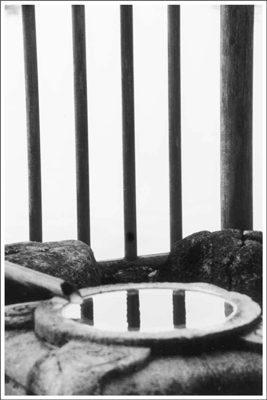

Photo by Cameron Broadhurst

W hen Zen arrived and began to take root in this country, there arose a misconception about the role of morality and ethics in the practice of the Buddhadharma. Statements that Zen was beyond morality or that Zen was amoral were made by distinguished writers on Buddhism, and people assumed that this was correct. Yet nothing can be further from the truth. Enlightenment and morality are one. Enlightenment without morality is not true enlightenment. Morality without enlightenment is not complete morality. Zen is not beyond morality, but a practice that takes place within the world, based on moral and ethical teachings. Those moral and ethical teachings have been handed down with the mind-to-mind transmission from generation to generation.

The Buddhist precepts form one of the most vital areas of spiritual practice. In essence, the precepts are a definition of the life of a Buddha, of how a Buddha functions in the world. They are how enlightened beings live their lives, relate to other human beings, make moral and ethical decisions, manifest wisdom and compassion in everyday life. The precepts provide a way to see how the moral and ethical teachings in Buddhism can come to life in the workplace, in relationships, in government, business, and ecology.

The first three precepts are vows to take refuge in the Three Treasuresthe Buddha, the Dharma, and the Sangha. Buddha is the historical Buddha, but at the same time Buddha is each being, each creation. Dharma is the teaching of the Buddha, but at the same time Dharma is the whole phenomenal universe. And Sangha is the community of practitioners of the Buddhas Dharma, but at the same time Sangha is all sentient beings, animate and inanimate.

The Three Pure Precepts are: not creating evil, practicing good, and actualizing good for others. The Pure Precepts define the harmony, the natural order, of things. If we eschew evil, practice good, and actualize good for others, we are in harmony with the natural order of all things.

Of course, it is one thing to acknowledge the Three Pure Precepts, but how can we practice them? How can we not create evil? How can we practice good? How can we actualize good for others? The way to do that is shown in the Ten Grave Precepts, which reveal the functioning of the Three Pure Precepts. The Ten Grave Precepts are: (1) Affirm life; do not kill, (2) Be giving; do not steal, (3) Honor the body; do not misuse sexuality, (4) Manifest truth; do not lie, (5) Proceed clearly; do not cloud the mind, (6) See the perfection; do not speak of others errors and faults, (7) Realize self and other as one; do not elevate the self and blame others, (8) Give generously; do not be withholding, (9) Actualize harmony; do not be angry, (10) Experience the intimacy of things; do not defile the Three Treasures.

The Sixteen Preceptstaking refuge in the Three Treasures, the Three Pure Precepts, and the Ten Grave Preceptsare not fixed rules of action or a code for moral behavior. They allow for changes in circumstances: for adjusting to the time, the particular place, your position, and the degree of action necessary in any given situation. When we dont hold on to an idea of ourselves and a particular way we have to react, then we are free to respond openly, with reverence for all the life involved.

When we first begin Zen practice, we use the precepts as a guide for living our life as a Buddha. We want to know how to live in harmony with all beings, and we do not want to put it off until after we get enlightened. So, we practice the precepts. We practice them the same way we practice the breath, or the way we practice a koan. To practice means to do. We do the precepts. Once we are aware of the precepts, we become sensitive to the moments when we break them. When you break a precept, you acknowledge that, take responsibility for it, and come back to the precept again. Its just like when you work with the breath in zazen. You sit down on your cushion and you vow to work with the breath, to be the breath. Within three breaths you find yourself thinking about something else, not being the breath at all. When that happens, you acknowledge it, take responsibility for it, let the thought go, and return to the breath. That is how you practice the breath, and that is how you practice the precepts. That is how you practice your life. Practice is not a process for getting someplace; it is not a process that gets us to enlightenment. Practice is, in itself, enlightenment.

Next page