SITTING WITH KOANS

Wisdom Publications

199 Elm Street

Somerville, MA 02144 USA

www.wisdompubs.org

2006 Dharma Communications Press

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photography, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system or technologies now known or later developed, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sitting with koans : essential writings on Zen koan introspection / edited

by John Daido Loori ; foreword by Thomas Yuho Kirchner.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-86171-369-9 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Koan. 2. MeditationZen Buddhism. I. Loori, John Daido.

II. Title: Essential writings on Zen koan introspection.

BQ9289.5.S59 2005

294.3443dc22

2005025144

First edition

09 08 07 06 06

5 4 3 2 1

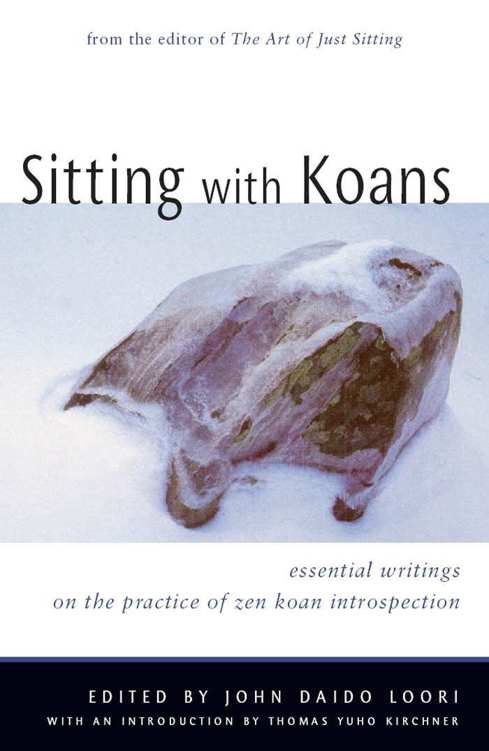

Cover design by Gopa & Ted2, Inc., and Josh Bartok.

Interior by Gopa & Ted2, Inc.

Cover photo John Daido Loori

Wisdom Publications books are printed on acid-free paper and meet the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Production Guidelines for Book Longevity set by the Council on Library Resources.

Printed in Canada.

C ONTENTS

I AM VERY GRATEFUL to all the masters, ancient and modern, whose teachings have been included in this volume. It was their wisdom, insight and skillful means that made this project possible. Special thanks to Vanessa Zuisei Goddard for her research and work in collecting the pieces included in this book. Her skillful editing and proofreading were indispensable, as was the editorial input of Konrad Ryushin Marchaj. Thanks to Josh Bartok of Wisdom Publications for recognizing the importance and need of a volume such as this for Western students, and for vigorously working toward its completion. Finally, a deep bow to the many students who provided assistance in the form of copy editing, graphic designing, indexing and the like. May the collective effort of the fine practitioners who contributed to the creation of this book nourish future generations on their spiritual journeys.

F EW ASPECTS OF B UDDHIST P RACTICE have so captured the popular imagination as the Zen koan. On first encounter koans seem the ultimate riddles, challenging us to transcend ordinary logic and offering the promise of spiritual insight. They are undoubtedly one of the main reasons for Zens association with intuitive creativity, and for the mystique that has inspired any number of book titles beginning with Zen and the Art of ....

For most people the mystery of the koans begins with the enigmatic wording of the koans themselves. Why would the Chinese master Zhaozhou Congshen reply, The juniper tree in the garden, when asked the meaning of Bodhidharmas coming from the west? When Baizhang Huaihai put a jug on the floor and said, If you cant call this a jug, what do you call it? why did his student Guishan Lingyou kick over the jug and walk away? And what does it signify that such enigmatic responses, properly understood, are equally meaningful for modern American Zen students as for Song-dynasty Chinese monks?

Questions of this type generally resolve themselves with serious zazen practice and deepening insight. Students find that koans have their own inner logic, a logic that reveals itself as practitioners come to know the mind out of which the koans emergeda mind beyond thought and time, in which, as John Daido Loori Roshi says in his Introduction, there are no paradoxes. Here Chinese monk and American Zen student stand on equal footing.

And yet with continued practice other, sometimes more perplexing, enigmas emerge. The effectiveness of the koans in Zen training has been demonstrated through the centuries, and many of the greatest masters, such as Dahui and Hakuin (both represented in the present volume), proclaim them incomparable as a way to precipitate awakening and clarify insight. Nevertheless, every long-time Zen practitioner knows certain intuitive individuals who are far advanced in koan work yet show little corresponding spiritual growth; this is as true among traditional Asian monastics as among Western lay practitioners. Conversely, other students, obviously mature in their practice, fail to ever connect with the koans, sometimes even after completing the entire system. Even Rinzai Zen masters often have misgivings about koan practice, warning against collecting koans at the risk of missing the true goal of Zen practice, which Dogen describes as, to be enlightened by the ten thousand things, to eliminate the separation between self and other.

Why do some individuals seem to do so well with koans, and others seem to miss the mark? There may be as many answers to this question as there are people practicing Zen. In the end, there are no guarantees in the spiritual life; no method or technique, no matter how powerful, can by itself entirely overcome the subtle self-deceptions used by the ego to perpetuate its own existence. The koan is simply a tool, an aid to self-inquiry and realization that, as Daido Roshi points out, must be supported by the personal foundation one brings to the practice: great doubt, great faith, and great determination. Without, in particular, great doubt (the drive to resolve the question of life and death), the student can easily mistake koans as the goal of Zen practice, rather than as a means to that goal.

In his excellent contribution to this collection, Victor Sogen Hori stresses that koan work, like all Buddhist practices, is ultimately concerned with attaining the religious ideals of awakened wisdom and selfless compassion. If the essentially religious nature of the training is not understood, then the central reason for these training methods has been missed. In practical terms, the various aspects of a comprehensive spiritual practice have their respective strengths and weaknesses; zazen and koan work tend to be oriented chiefly towards deepening and clarifying the aspect of wisdom, and achieve their ultimate goals best when balanced by more explicitly compassion-oriented work in ethics and character development.

Nevertheless, to acknowledge that the koan is a tool, with a tools limits, is not in any way to belittle it. Tools are as essential in cultivating the spiritual life as they are in cultivating the soil of a garden. For many Zen practitioners the koan has proved an especially effective means of crystallizing the problems that arise on the spiritual path and precipitating the insights that help resolve those problems. The challenge is to employ the koan-tool most effectively, and that, as with any tool, requires an understanding of what it is and how it is used.

Sitting with Koans provides an excellent start toward such understanding, offering the readerwhether veteran meditator, inquiring novice, or simply interested observera careful and well-organized presentation of classic and modern source materials on many aspects of traditional koan work. Chapters on the meaning, history, and dynamics of koan practice are accompanied by a large selection of actual koans, with commentaries by Chinese, Japanese, and American Zen masters. Solidly oriented toward the religious dimension of Zen, the books emphasis is always on the koan as a spiritual practice.

Sitting with Koans joins Daido Roshis many other books to form a body of work dealing with virtually every aspect of practical Zen training, including shikantaza (The Art of Just Sitting), ethics and morality (The Heart of Being), the stages of practice (Riding the Ox Home), and art as spiritual training (The Zen of Creativity). One of Daido Roshis central goals as a teacher has been the integration of traditional Buddhist values into the cultural context of twenty-first century America, centered on the creation of a viable Buddhist monasticism that supports and is in turn sustained by a solid lay practice. Sitting with Koans continues this effort, clarifying the nature and history of koan training and demonstrating how it continues to evolve in the present-day Western world. This is a book that will be of value to anyone interested in koan practice and the transmission of this practice to the West.