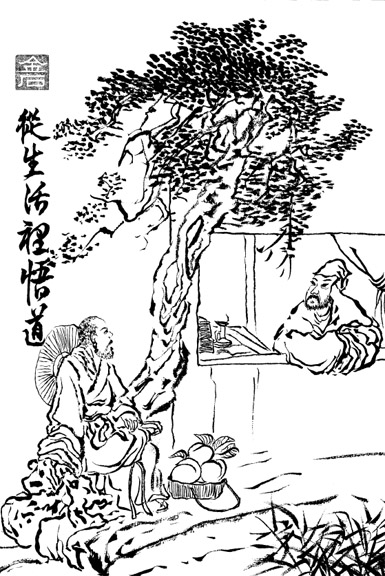

Realize the Way Through Everyday Living

THERE was once a young master by the name of Lung T'an who paid a visit to Ch'an master Tao Wu. "In the place where I come from," he said to Tao Wu, "I never felt that it was you who supposedly formed my aspirations instead of me."

THERE was once a young master by the name of Lung T'an who paid a visit to Ch'an master Tao Wu. "In the place where I come from," he said to Tao Wu, "I never felt that it was you who supposedly formed my aspirations instead of me."

"In the place where you come from," replied the master, "there was not a moment when I didn't form your aspirations."

Disagreeing, Lung T'an showed his displeasure. "What do you mean by that?"

"As things are," argued Tao Wu, "when you send me your tea I receive it; when you bring me your rice I take it from you. Now, when you bow to me I return it with a nod. Say, what is wrong? Dare you say that I don't form your aspirations anywhere you are?"

Lung T'an couldn't find an answer. He bowed his head in thought and was silent for a long time.

"Those who realize completely do not have the slightest doubt whether it is true Enlightenment or not," said Tao Wu.

After hearing this, Lung T'an attained instant realization. He asked the master, "From now on, what should I do in order to keep this state of Enlightenment?"

"It costs nothing to do this," said the master, "just follow your self-nature. When you want to be leisurely and carefree, please, go traveling on the Four Seas like a floating cloud. Adapt yourself to the circumstances and don't worry about aftereffects. In the light of everyday living, clear your mind and never analyze your activities in forms of folly and wisdom. That's all."

Commentary: Seeking the Way, one need not do anything supernatural. The simplest method of entering the Way is to realize it through one's daily life, wearing clothes, eating food, standing, and walking. Hence, one shouldn't be afraid of mortal troubles, because it is said that the Way is not to be found outside the mundane world. The beginning of the Diamond Sutra describes how Buddha put on his robe, carried his bowl, and went on his alms rounds. "He went to the large cities begging for food. Then he came back to his place and ate. Then he put away his robe and bowl and washed his body. If there was shelter for the night he went there to sleep...." This depicts no difference between the ascetic life and the lives of ordinary people. However, the state of mind of an ordinary being is markedly different from the state of mind of an Enlightened being in the pursuit of everyday life. The question for those who are seeking the Way is not "Who are you?" but "How are you to realize this in daily life?"

Actually, people do not need to isolate themselves from the community in order to practice the Way. As it is said in the classic Chung Yung, "The Way is not something that alienates people. The idea of alienation is due to those who isolate themselves from the community for the sake of so-called entering the Path, while in effect getting further and further away from the Truth."

A Withered Tree, a Splendid Tree

ONCE, WHEN the venerable master Yao Shan held the position of abbot, he was walking in a temple courtyard in the company of his two disciples, Tao Wu and Yun Yen. Two trees stood in front of the temple. One was withered and the other was in full splendor. Pointing at the trees the master asked, "Which of these trees is following the right way, the withered one or the one in splendor?"

ONCE, WHEN the venerable master Yao Shan held the position of abbot, he was walking in a temple courtyard in the company of his two disciples, Tao Wu and Yun Yen. Two trees stood in front of the temple. One was withered and the other was in full splendor. Pointing at the trees the master asked, "Which of these trees is following the right way, the withered one or the one in splendor?"

"The one in splendor," replied Tao Wu.

"The brightness blinds the eyes," commented the master. He asked again, "Which is correct, a withered tree or one in splendor?"

"A withered one," answered Yun Yen.

"It is dominated by dullness," explained the master.

At this point they were joined by a monk, and Yao Shan asked him the same question.

"A withered tree complies with the withering of itself," the monk retorted, "a splendid tree follows its own splendor."

"No! No!" exclaimed the master, addressing his disciples.

Commentary: In ordinary people's thinking, all things can be differentiated by name and related to in terms of duality. In this case, "a tree in splendor," reflecting the positive concept of "is," was the answer chosen by Tao Wu. The master, however, didn't approve of this answer. On the other hand, "a withered tree," representing the negative concept, or "is not," was preferred by Yun Yen, but the master's reply indicated the equal delusion of Yun Yen's mind. Although the monk didn't choose either of the two opposing concepts, his answer assumed the existence of both and proved the fact that he wasn't released from the chain of rebirth and death. That's why the master couldn't accept the monk's answer, exclaiming, "No! No!" He did this not only to protest the error, but first and foremost to rouse his disciples' doubts, letting them come to an understanding on their own.

It's Just Like This

UPON becoming Enlightened, Ch'an master Tung Shan went to pay the elder master Yun T'an his respects and ask him a question which had remained unresolved in his mind for many years. "What should I reply, Master," was the question, "when in a hundred years someone asks me whether I remember your real features or not?"

UPON becoming Enlightened, Ch'an master Tung Shan went to pay the elder master Yun T'an his respects and ask him a question which had remained unresolved in his mind for many years. "What should I reply, Master," was the question, "when in a hundred years someone asks me whether I remember your real features or not?"

Giving him a bright glance, he said simply, "It's just like this."

Commentary: The true nature of the self is in our minds, as a single whole which cannot be divided into halves by the use of spoken language.

The Ch'an masters sometimes teach their disciples by remaining silent, sometimes with interruption, sometimes by uttering a lion's roar, sometimes by facial expression or simple gesture; leaving aside the use of words and concepts of relativity, and expressing the single whole. This kind of special education shows the uniqueness of Ch'an.

Worship of Buddha

THERE WAS once a master by the name of Huang Nieh who paid a visit to Ch'an master Yen Kuang. Entering the temple, he knelt respectfully before a statue of Buddha. At this time, a young emperor of the T'ang dynasty named Hsuan Tsung was attending his religious service there as a novice. By chance, he was in the Buddha Hall and saw everything Huang Nieh performed.

THERE WAS once a master by the name of Huang Nieh who paid a visit to Ch'an master Yen Kuang. Entering the temple, he knelt respectfully before a statue of Buddha. At this time, a young emperor of the T'ang dynasty named Hsuan Tsung was attending his religious service there as a novice. By chance, he was in the Buddha Hall and saw everything Huang Nieh performed.

"For one who seeks the Truth," Hsuan Tsung then dared to say, "there is no need to worship Buddha or become a monk, or be an adherent of any teaching. Say, Master, why do you pay your respects to the statue of Buddha?"

"Since I need not worship Buddha, or become a monk, or be an adherent of any teaching, I do it," the master replied without delay. "I free myself, that's all."

After pondering the matter a considerable while, the novice asked, "What is the use of the forms of worship, master?"

Huang Nieh slapped him in the face in reply.

"Why, how rude!" the young emperor said, enraged. "How boorish you are!"

"Why?!" retorted the master. "You still dare to discuss who is boorish and who is notthis is really going too far!" said Huang Nieh, to the shame of Hsuan Tsung.

Commentary: In the Ch'an school there is a warning: "Those who recite the Buddha's name once have to rinse their mouths for three days." The Ch'an masters believe that seeing the nature of the self and attaining Buddhahood is a personal matter. It is not possible to realize the Truth by depending on others, including the Buddha. On the other hand, we know how often the Ch'an masters allow themselves to swear at Buddhas. In the Ch'an tradition, there is even the ritual of the burnt Buddha. All this is used to destroy any distinction between "I" and "Buddha" in the practitioner's mind, but not to profane the name of Buddha. Hsuan Tsung thought to himself, "I am the emperor." That is why, although a novice, he dared break into the elder master's worship, and was duly rebuffed. Through the slap, the master destroyed his concept of "emperor" and "subject," showing that the temple was a temple, not the imperial court.

THERE was once a young master by the name of Lung T'an who paid a visit to Ch'an master Tao Wu. "In the place where I come from," he said to Tao Wu, "I never felt that it was you who supposedly formed my aspirations instead of me."

THERE was once a young master by the name of Lung T'an who paid a visit to Ch'an master Tao Wu. "In the place where I come from," he said to Tao Wu, "I never felt that it was you who supposedly formed my aspirations instead of me."

ONCE, WHEN the venerable master Yao Shan held the position of abbot, he was walking in a temple courtyard in the company of his two disciples, Tao Wu and Yun Yen. Two trees stood in front of the temple. One was withered and the other was in full splendor. Pointing at the trees the master asked, "Which of these trees is following the right way, the withered one or the one in splendor?"

ONCE, WHEN the venerable master Yao Shan held the position of abbot, he was walking in a temple courtyard in the company of his two disciples, Tao Wu and Yun Yen. Two trees stood in front of the temple. One was withered and the other was in full splendor. Pointing at the trees the master asked, "Which of these trees is following the right way, the withered one or the one in splendor?" UPON becoming Enlightened, Ch'an master Tung Shan went to pay the elder master Yun T'an his respects and ask him a question which had remained unresolved in his mind for many years. "What should I reply, Master," was the question, "when in a hundred years someone asks me whether I remember your real features or not?"

UPON becoming Enlightened, Ch'an master Tung Shan went to pay the elder master Yun T'an his respects and ask him a question which had remained unresolved in his mind for many years. "What should I reply, Master," was the question, "when in a hundred years someone asks me whether I remember your real features or not?"

THERE WAS once a master by the name of Huang Nieh who paid a visit to Ch'an master Yen Kuang. Entering the temple, he knelt respectfully before a statue of Buddha. At this time, a young emperor of the T'ang dynasty named Hsuan Tsung was attending his religious service there as a novice. By chance, he was in the Buddha Hall and saw everything Huang Nieh performed.

THERE WAS once a master by the name of Huang Nieh who paid a visit to Ch'an master Yen Kuang. Entering the temple, he knelt respectfully before a statue of Buddha. At this time, a young emperor of the T'ang dynasty named Hsuan Tsung was attending his religious service there as a novice. By chance, he was in the Buddha Hall and saw everything Huang Nieh performed.