Praise for

Alejandro Jodorowsky

and His Works

No one alive today, anywhere, has been able to demonstrate the sheer possibilities of artistic inventionand in so many disciplinesas powerfully as Alejandro Jodorowsky.

NPR BOOKS

Alejandro Jodorowsky is a demiurge and an interpreter of our stories, always exploring further the understanding of both the beauty and complexity revealed by humankind.

DIANA WIDMAIER PICASSO, ART HISTORIAN

Jodorowsky is a brilliant, wise, gentle, and cunning wizard with tremendous depth of imagination and crystalline insight into the human condition.

DANIEL PINCHBECK, AUTHOR OF BREAKING OPEN THE HEAD

Alejandro Jodorowsky seamlessly and effortlessly weaves together the worlds of art, the confined social structure, and things we can only touch with an open heart and mind.

ERYKAH BADU, ARTIST AND ALCHEMIST

One of the most inspiring artists of our time.... A prophet of creativity.

KANYE WEST, RECORDING ARTIST

The Dance of Reality begs to be read as a culminating work....

LOS ANGELES TIMES

The Dance of Reality [film] is a trippy but big-hearted reimagining of the young Alejandros unhappy childhood in a Chilean town....

NEW YORK TIMES MAGAZINE

Manual of Psychomagic is great... like a cookbook of very useful recipes that can help us to understand our life and the universe we live in.

MARINA ABRAMOVI, PERFORMANCE ARTIST

His films El Topo and The Holy Mountain were trippy, perverse, and blasphemous.

WALL STREET JOURNAL

The best movie director ever!

MARILYN MANSON, MUSICIAN, ACTOR, AND MULTIMEDIA ARTIST

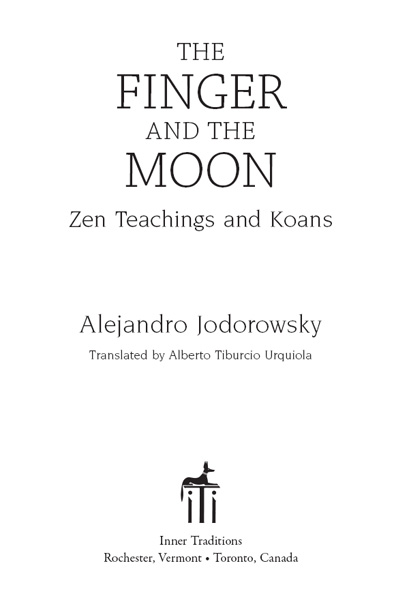

PROLOGUE

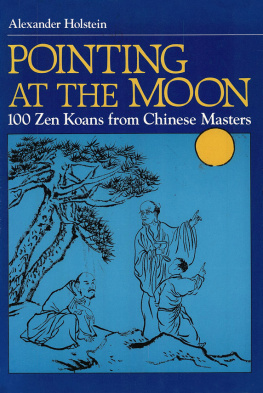

During the late 1950s, Zen master Yamada Mumon sent his disciple Ejo Takata from Japan to visit a North American zendo in, if I remember correctly, San Francisco. Once there, following his masters orders, he looked for a location to found a Zen Rinzai school. His method of searchingsince he spoke only Japaneseconsisted of not looking for it. He stood at the edge of a road and decided to establish the school wherever he was dropped off by the first vehicle to give him a ride. A truck carrying oranges left him in Mexico City with no clothes other than his koromo (monastic robe) and just ten dollars in his pocket. In that immense city of twenty million people, he wandered through the streets for an hour until a psychoanalyst, a disciple of psychologist Erich Fromm, happened to drive down the road. Fromm is the author of, among other things, a book called Zen Buddhism and Psychoanalysis, and at that time he had just discovered Zen through the works of D. T. Suzuki.

The psychoanalyst was surprisedor, more precisely, astonishedto see a Japanese man calmly wandering the streets of Mexico City and invited Takata to join him in the car. He considered the monks arrival to be a major event in the development of his new school. Along with a group of physicians and psychoanalysts, he installed Takata, who would eventually become my master, in a zendo on the outskirts of the capital.

At that time all that we knew about Zen had come from some books that had been poorly translated into Spanish. The koans appeared to our logical spirits as unresolvable mysteries. And we imagined an enlightened Zen master to be a wizard capable of answering all our metaphysical doubts, and even of giving us the power to defeat death.

After struggling quite a bit to get in touch with the master, one fine day, shaking with excitement, I finally knocked at his door. A smiling Asian man with a shaved head, of uncertain agehe could have been in his twenties or his sixtiesand wearing monks attire, opened the door and immediately treated me as though I had been his lifelong friend. He took me by the hand, led me to the meditation room, and showed me a piece of white cloth hanging on the wall inscribed with a Japanese word he hastily translated and pronounced with difficulty: happiness.

This is how my experience with Ejo Takata started. That year I wrote down some impressions thathowever nave and despite being expressed by an idealistic teenagerhave never ceased, in my view, to be valid. Years have passed, but the respectful love I professed to Ejo Takata has never disappeared from what I can simply call my soul. My interpretations of the stories and koans originate from my encounter with this both great and humble master. (About his life in Japan, I know nothing but this anecdote: While the Americans were bombing Tokyo, in the middle of a rain of bombs, he continued meditating.)

Experience with Ejo Takata

(Mexico, 1961)

The first time I went to the zendo, the master showed me a poem that ended like this:

He who has nothing but feet will contribute with his feet.

He who has nothing but eyes will contribute with his eyes to this great spiritual work.

Throughout his prayers, the master coughs and sneezes. I just try to meditate, barely daring to breathe.

The master no longer prays.

These chants are him. The prayers cough and sneeze.

The student meditated in a corner of the zendo. Fearing that it might become a habit, he went to the opposite corner.

He passed through the four corners of the zendo, and through all the places where people meditated. The master always meditated in the same place; however, nothing was done by rote.

The disciple insisted on taking off his shoes before entering the zendo, with its hardwood floor. He had dirtied his feet. As he sat down on the wooden parquet, he stained it.

The master only took off his shoes when he sat in his place.

When he went to the masters house, the disciple took off his shoes so that he would not stain the floor, but when he visited his friends, he didnt even bother to wipe the soles of his shoes on the mat at the entrance.

The master invited the disciple to sit in the garden. He took out a straw chair and brought it. But halfway through, he gave the chair to the disciple.

The master said,

From Mexico City we can see Popocatepetl. But from Popocatepetl we cant admire Popocatepetl.

When the master prayed, his words produced a musical vibration. I was grateful for this sound because it made my cells vibrate; it put them in order, like a magnet, in one direction. The words became irrelevant to me.

Before departing, the master wanted to give me his canethe keisakuas a gift.

These were my feelings: If you have a cane, Ill take it from you; if you dont, Ill give one to you. Oh, infinite mercy! I do not thank you. I didnt have one and you wanted to give it to me. Now I have it, so take it away from me. Only thus would you have truly given it to me. Allow me to refuse your gift. One day my hands will blossom, and I will not need a cane because I will be able to strike your shoulder with my palm (and with my fingers).

The master said: If you do a good deed and you tell someone about it, you lose any benefit it might have brought to you. But he boasted about every good deed he did. He advertised it, not out of vanity but to avoid any inner gain for himself.

He wanted to do good without asking for anything in return.

A temple is not the exclusive place of the sacred. We go to the temple to learn the sense of the sacred. If the lesson has been understood, the entire earth becomes a temple, every man becomes a priest, and every food is a Communion host.

The master strikes me twice on the shoulder with his keisaku, which is a long, thin cane with a flat end. It has Japanese characters engraved on both ends. I ask him what they mean.

Next page