A

BOOK

The Philip E. Lilienthal imprint

honors special books

in commemoration of a man whose work

at the University of California Press from 1954 to 1979

was marked by dedication to young authors

and to high standards in the field of Asian Studies.

Friends, family, authors, and foundations have together

endowed the Lilienthal Fund, which enables the Press

to publish under this imprint selected books

in a way that reflects the taste and judgment

of a great and beloved editor.

The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous

contribution to this book provided by the Philip E.

Lilienthal Asian Studies Endowment of the University

of California Press Associates, which is supported by

a major gift from Sally Lilienthal.

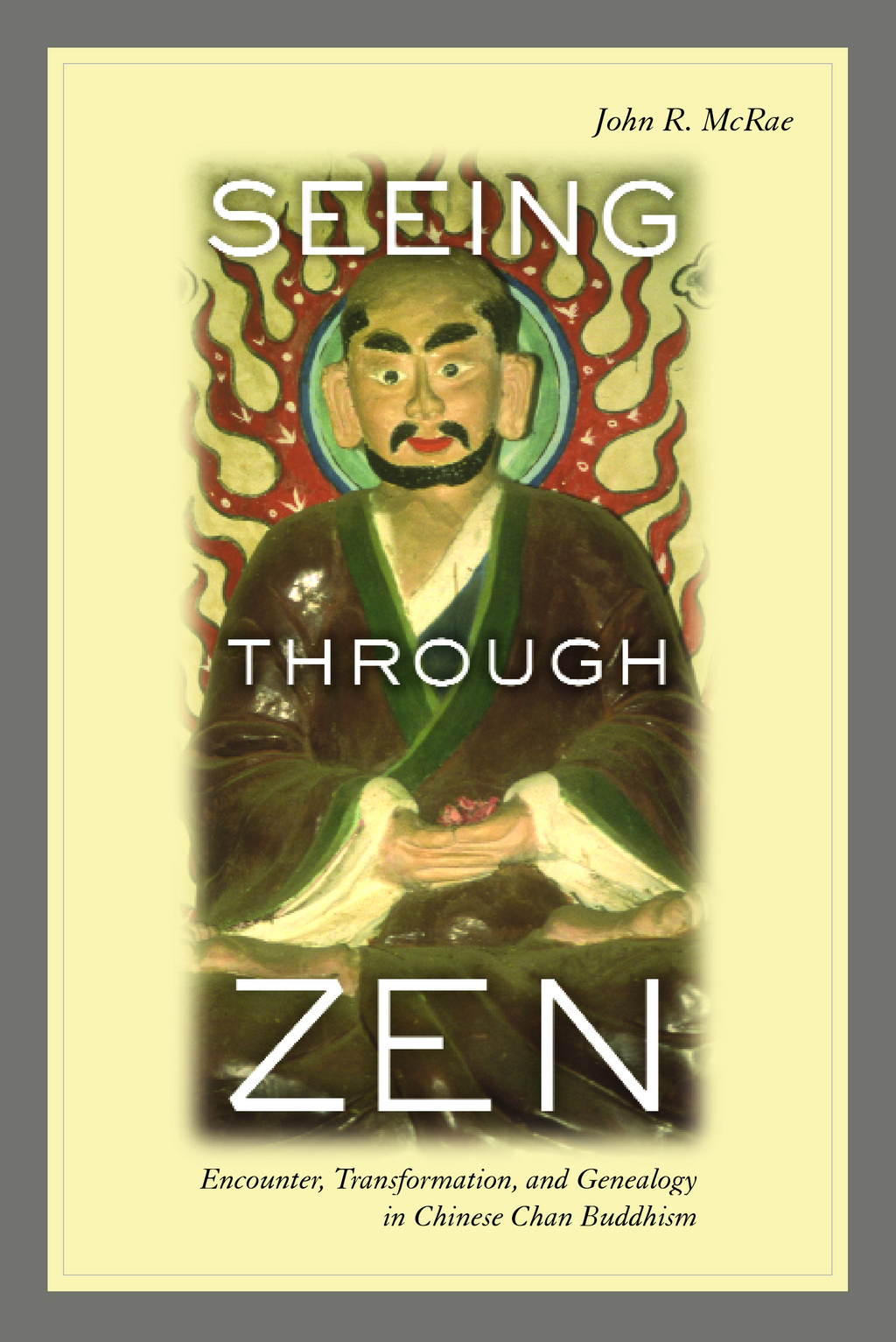

Seeing through Zen

Seeing through Zen

Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism

John R. McRae

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

Berkeley / Los Angeles / London

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2003 by the Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

McRae, John R., 1947

Seeing through Zen : encounter, transformation, and genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism / John R. McRae.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-520-23797-8 (alk. paper)ISBN 0-520-23798-6 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Zen BuddhismChinaHistory. I. Title.

BQ9262.5 .M367 2004

294.3'927'0951dc21 | 2003011741 |

Manufactured in the United States of America

13 12 11 10 09 08 07 06 05 04

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication is both acid-free and totally chlorine-free (TCF). It meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.481992(R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

Dedicated to YANAGIDA Seizan, with inexpressible gratitude

Contents

Illustrations

Figures |

Frontis: | Bodhidharma crossing the Yangzi on a reed, by Young-hee Ramsey |

Maps |

Preface

This book is intended for those who wish to engage actively in the critical imagination of medieval Chinese Chan, or Zen, Buddhism. The interpretations presented in the following pages represent my best and most cherished insights into this important religious tradition, and I look forward to their critical appraisal and use by general readers, students, and colleagues. More important than the specific content presented here, though, are the styles of analysis undertaken and the types of human processes described. In other words, the primary goal of this book is not to present any single master narrative of Chinese Chan, but to change how we all think about the subject.

I expect the readership of this book to include Zen and other Buddhist practitioners; students and scholars of Chinese religions, Buddhist studies, and related fields; and a general audience interested in Asian religions and human culture. General readers will find here sufficient basis for a far-reaching critique of how Zen is perceived in contemporary international culture. In addition, my analysis of Chinese Chan religious practice as fundamentally genealogical should provide a new point of comparison for the analysis of modern and contemporary developments in Zen, particularly those occurring in North America and Europe. That is, if Chan practice was originally genealogicalby which I mean patriarchal, generational, and relationalin ways that fit so well with medieval Chinese society, how will it be (or, how is it being) transformed as it spreads throughout the globe in the twenty-first century (and as it did in the twentieth)? In other words, how is Zen changing, and how will it change, as it grows and spreads within the context of globalization and Westernization?

Scholars, students, and general readers constitute a natural audience for this book. Why should religious practitioners read it? If Buddhist spiritual practice aims at seeing things as they are, then getting past the foolish over-simplifications and confusing obfuscations that surround most interpretations of Zen should be an important part of the process. That is the short answer. A more specific answer requires a bit of explanation.

The first time I lectured on Chinese Chan to a community of practitioners was in 1987 for the Summer Seminar on the Sutras, held in Jemez Springs, New Mexico, at Bodhi Mandala, which functions within the teaching organization of the Rinzai master Joshu Sasaki Roshi. Among those attending was an elderly American Zen monk, who objected strenuously to my instruction, asking repeatedly, What good is any of this for my practice? The organizers of the week-long workshop were somewhat embarrassed by his aggressive attitude, pointing out that, as a former lightweight boxer, he may have taken more than one punch too many. For my own part, I enjoyed the challenge, which forced me to confront the question head-on in a way that never would have happened in university lecturing. Subsequently, I have honed my response (you are welcome to consider it a defensive reaction, if you wish!) in seminars and workshops at Dai Bosatsu in upstate New York, under the direction of another Rinzai teacher, Eido Shimano Roshi; the Zen Center of Los Angeles, a Soto Zen institution founded by the late Taizan Maezumi Roshi; Zen Mountain Monastery at Mt. Tremper, New York, led by John Daido Loori Roshi, a student of Maezumis; the San Francisco Zen Center, which was founded by Shunryu Suzuki Roshi; the Mount Equity Zen Center, directed by Dai-En Bennage Sensei; Zen Mountain Center, directed by Tenshin Fletcher Sensei, a successor to Maezumi; and Dharma Rain and the Zen Community of Oregon in Portland, directed by Kyogen and Gyokuko Carlson and Chozen and Hogen Bays, respectively. In addition to these American Zen centers, on two separate occasions, I have also taught a two-week intensive class at Foguang Shan in Kaohsiung, Taiwan; on the first occasion (in 1992) the participants were mostly young Taiwanese Buddhist nuns, while on the second (in 2002) the class was composed of Southeast Asian Chinese nuns and monks from Africa, India (a native of N land

land !), and the United States. These chapters were first prepared for presentation at Templo Zen Luz Serena in Valencia, Spain, under the direction of Dokush

!), and the United States. These chapters were first prepared for presentation at Templo Zen Luz Serena in Valencia, Spain, under the direction of Dokush Villalba Sensei. This book has benefited in profound ways from interaction with the participants in all these different practice settings, and I am deeply grateful for their attention, questions, and suggestions.

Villalba Sensei. This book has benefited in profound ways from interaction with the participants in all these different practice settings, and I am deeply grateful for their attention, questions, and suggestions.

There is nothing in this book that will aid ones religious practice directly. I am not a Zen master, nor even a meditation instructor, and this is not a do-it-yourself manual. To use a cooking analogy, I am not a Julia Child teaching you how to concoct your life in Zen. Instead, I am more the art critic who evaluates her teaching methods and dramatic performance, or even the chemist who analyzes the dynamic evolution of her recipes as they make their pilgrimage from pan to plate. Art critics are not necessarily good performers themselves, and chemists are not necessarily gourmet cooks. Although I am indeed a Buddhist (in autobiographical blurbs I usually include a line about being a practitioner of long standing but short attention span), and even though my religious identity as a youthful convert to Buddhism allows for a certain empathy with my subject matter, I am a scholar and not a guru. As a professor in aggressively secular state universities over the years, I have learned to keep anything resembling preaching out of my classroom presentations, and the same holds true here. I am not aiming to convert you, unless by that is meant an intellectual transformation that may penetrate to the very core of your being.

land

land Villalba Sensei. This book has benefited in profound ways from interaction with the participants in all these different practice settings, and I am deeply grateful for their attention, questions, and suggestions.

Villalba Sensei. This book has benefited in profound ways from interaction with the participants in all these different practice settings, and I am deeply grateful for their attention, questions, and suggestions.