Introduction

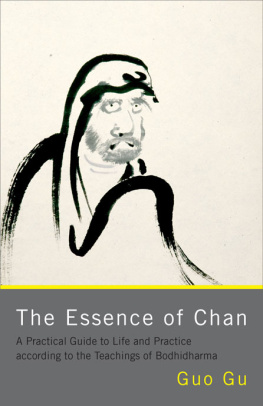

THIS BOOK TRAVELS a path at the heart of Chinese culture. It follows the tracks left by Bodhidharma, a fifth-century Indian monk and important religious figure remembered as the founder of Zen Buddhism. I trace his path in China to unearth forgotten stories that shaped a civilization and reveal the roots of the religion that dominated East Asia for fifteen centuries.

This is also a personal journey, for it explores the origins and significance of Zen, a tradition I have practiced and studied for several decades.

The trail also leads into some little-known corners of Chinese history, places in the shadows of East Asia that continue to influence the regions development.

Bodhidharma, an Indian Buddhist missionary, traveled from South India to China sometime around the year 500 CE. Although his Zen religion spread relatively quickly from China to Korea and Vietnam, it was another seven hundred years before Zen finally took root in Japan, the country Westerners most frequently associate with the religion.

While Bodhidharmas teachings are known in the West as Zen, a Japanese word, the term is equivalent to the modern Chinese word Chan. This book uses the word Zen because it is familiar to Western audiences. Bodhidharma was the First Ancestor or First Patriarch of the Zen (Chan) sect in China.

Zen claims that successive generations of teachers have relayed its essential insight by mind-to-mind transmission. The religions founding myth claims that this transmission started when the historical Buddha, Shakyamuni, sat before a crowd of his followers at Vulture Peak, a place in ancient India. There, says the legend, he held up a flower before the assembly. In response to this gesture, his senior disciple Mahakasyapa smiled, whereupon the Buddha uttered the words that purportedly set in motion centuries of awakening:

I have the treasury of the true Dharma Eye, the sublime mind of nirvana, whose true sign is signlessness, the sublime Dharma Gate, which without words or phrases is transmitted outside of the [standard Buddhist] teachings, and which I bestow upon [my disciple] Mahakasyapa.

The Zen tradition thus declared and originated its essential insight into the signless mind of nirvana, which can be interpreted as the nature of normal human (or any sentient beings) consciousness, which by nature is outside of time and space. In the story, the Buddha metaphorically refers to the field of consciousness (which is usually translated as mind) as the Treasury of the True Dharma eye.

As Zen developed in China, it claimed that Bodhidharma taught a refined summation of this essential Zen teaching. Bodhidharma purportedly said, Not setting up words, a separate transmission outside the [scriptural] teachings, point directly at the human mind, observe its nature and become Buddha. (

)

The Zen tradition that coalesced from this perspective held sway as Chinas dominant and orthodox religion for the next fifteen hundred years. The cultural impact of Zen on East Asia can hardly be understated. This impact is perhaps best known as underlying the aesthetics of much East Asian art and literature, where landscape paintings, poetry, and other arts often reveal Zens spare perspective.

In China, Bodhidharma taught his Zen to a Chinese disciple named Huike (pronounced Hway-ka). This Second Ancestor is credited to have transmitted Bodhidharmas teachings to others in that country. Some records indicate that Chinas religious and political establishment initially rejected Bodhidharmas Zen movement, persecuting Bodhidharma and Huike as heretics. Accounts claim that certain religious rivals poisoned Bodhidharma and that others denounced his disciple Huike to the authorities. Those authorities reportedly executed Huike, then cast his corpse into a river.

Trouble with high authorities notwithstanding, Bodhidharma and his movement had wide impact even during his lifetime. A reliable record indicates that the sage traveled widely, and that his followers were like a city. Having a large following and operating outside the political and religious establishment is often, of course, highly dangerous, so accounts of Bodhidharmas persecution by religious rivals and political circles seem credible.

Bodhidharmas legendary life grew in mythical detail as time passed and his religious message gained acclaim. This book examines the traditional account of his life. It also offers a different perspective, a view removed from prevailing religious and scholarly orthodoxy about Bodhidharma held in East Asia and the West. The narrative reinterprets and pieces together evidence to support a new perspective about this critical figures life and importance. The accounts make use of the most reliable sources and shed new light on why later generations regarded Bodhidharma as such an important religious leader.

This is not simply an academic question. The ramifications of Bodhidharmas life and what he symbolized to China are only now becoming fully clear, and they extend to events that have shaped recent East Asian history. On the macro level, unraveling Bodhidharmas story reveals the roots of a narrative still being argued and even fought over in East Asia.

Besides Bodhidharma, two other figures who lived at or about his time play prominent roles in this narrative. One is Chinas great Tang dynasty Buddhist historian and scholar Daoxuan (pronounced Dow Swan) (596667 CE). This remarkable man not only personally unified much of Chinese Buddhism but also chronicled in detail its people, thought, and movements. We can thank him for keeping Bodhidharmas life planted on the earth instead of floating in mythical clouds. Daoxuans historical records play heavily in this story.

The other figure is an emperor. At the core of Bodhidharmas legend is his fabled encounter with Emperor Wu of the Liang dynasty, called the Bodhisattva Emperor (in East Asian Buddhism, a bodhisattva is an exalted spiritual being). Wus reign (502549 CE) represents the fusion of the Buddhist religion with Chinese state power and authority. Emperor Wu wedded his brilliant understanding of Buddhist tradition and theory with Confucian statecraft. The result served as the ideological basis of Wus empire and reverberated through East Asian history. No thorough understanding of China and East Asia can overlook the critical developments that came from Emperor Wu. For this reason, this book looks at Emperor Wus life in some detail. His intriguing story is the essential counterpoint to Bodhidharma, and the significance of each of these historic figures cannot be calculated without an understanding of the other.

As I said, I explore these questions while tracking Bodhidharmas ancient trail through China. Along the way are places that Bodhidharma lived and taught, places that reveal the cultural aftermath of his passing.

People with little prior knowledge of Zen may here have a first look at part of this deep wellspring of Chinese and East Asian culture. For readers with more prior knowledge of Zen history, the book should throw new light on the traditions early years. But I hope that thoughtful readers with no knowledge whatsoever about Zen, about Bodhidharma, or even about Chinese history can here find an illuminating account of a critical story of East Asia history, a story that informs a better understanding of that region.

)

)