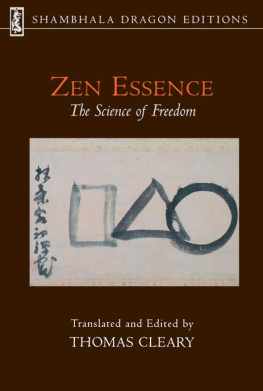

One of the foremost contemporary translators of classical Buddhist and Taoist literature.

Library Journal

There is no doubt in my mind that Thomas Cleary is the greatest translator of Buddhist texts from Chinese or Japanese into English of our generation, and that he will be so known by grateful Buddhist practitioners and scholars in future centuries. Single-handedly he has gone a long way toward building the beginnings of a Buddhist canon in English.

Robert A. F. Thurman, Tricycle

ABOUT THE BOOK

Founded by Bodhidharma centuries ago in China, Zen and its teachings have since spread widely, exerting a tremendous cultural influence not only across Asia, but also the modern West. To this day, Zen inspires young and old, from all walks of life, to see the world with fresh eyesbeyond our usual assumptions and prejudices.

This compendium of a thousand years of Zen teaching presents the essence of the tradition through stories, sayings, talks, and records of heart-to-heart encounters with Zen masters. The great expositors of the tradition, whose voices are recounted here, encourage us to let go of our clinging and intellectual grasping, and to open ourselves to embrace reality exactly as it is.

THOMAS CLEARY holds a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University and a JD from the University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He is the translator of over fifty volumes of Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Islamic texts from Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Pali, and Arabic.

Sign up to learn more about our books and receive special offers from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/eshambhala.

THE ZEN READER

Compiled and translated by

THOMAS CLEARY

SHAMBHALA

Boston & London

2011

Shambhala Publications, Inc.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, MA 02115

www.shambhala.com

1999 by Thomas Cleary

Cover art: Originally Not One Thing by Goyo.

Used with permission of John Stevens.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUES

THE PREVIOUS EDITION OF THIS BOOK AS FOLLOWS:

The pocket Zen reader/compiled and translated by Thomas Cleary.1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN 978-0-8348-2278-8

ISBN 978-1-57062-447-6 (paper: alk. paper)

ISBN 978-1-59030-636-9

1. Zen BuddhismQuotation, maxims, etc.

I. Cleary, Thomas F., 1949

BQ9267.P63 1999 98-39908

294.3 927DC2I CIP

Contents

ZEN IS traditionally called the School of the Awakened Mind, or the Gate to the Source. The premise of Zen is that our personality, culture, and beliefs are not inherent parts of our souls, but guests of a recondite host, the Buddha-nature or real self hidden within us. We are not limited, in our essence or mode of being, to what we happen to believe we are, or what we happen to believe the world is, based on the accidental conditions of our birth and up-bringing.

This realization may not seem to have positive significance at first, until it is remembered how much anger, antagonism, and grief arises from the ideas of them and us based on historically conditioned factors like culture, customs, and habits of thought. Any reasonable person knows these things are not absolute, and yet the force of conditioning creates seemingly insurmountable barriers of communication.

By actively awakening a level of consciousness deeper than those occupied by conditioned habits of perception, the realization of Zen removes the strictures of absolutism and intolerance from the thinking and feeling of the individual. In doing so, Zen realization also opens the door to impartial compassion and social conscience, not in response to political opportunity, but as a spontaneous expression of intuitive and empathic capacities.

This book is a collection of quotations from the great Eastern masters of Zen. It has no beginning, middle, or end. The masters talk about the practicalities of Zen realization in many different ways, speaking as they did to different audiences in different times, but all of them are talking about waking up, seeing for yourself, and standing on your own two feet. Start anywhere; eventually youll come full circle.

by the Founder of Zen

T HERE ARE many avenues of entry into the Way, but they are essentially of just two types, referred to as principle and conduct.

Entry by principle is when you realize the source by way of the teachings and deeply believe that all living beings have the same real essential nature, but it is veiled by outside elements and false ideas and cannot manifest completely. If you abandon falsehood and return to reality, abiding stably in impassive observation, with no self and no other, regarding ordinary and holy as equal, persisting firmly, immovable, not following other persuasions, then you deeply harmonize with the principle. Having no false notions, being serene and not striving, is called entry by way of principle.

Entry by conduct refers to four practices in which all other practices are included. What are the four? First is compensation for opposition. Second is adapting to conditions. Third is not seeking anything. Fourth is acting in accord with truth.

The practice of compensation for opposition means that when people cultivating the Way are beset by suffering, they should think how in past times they themselves neglected the fundamental and pursued the trivial over countless ages, flowing in waves of existences, arousing much enmity and hatred, with no end of offense and injury. Although they may be innocent right now, they think of their suffering as the results of their own past evil deeds, not something inflicted upon them by gods or humans. Thus they accept contentedly, without enmity or complaint. Scripture says, There is no anxiety when experiencing suffering, because of perfect knowledge. When this attitude is developed, you are in harmony with the Way. Because we make progress on the Way by comprehending opposition, this is called the practice of compensating for opposition.

Second is the practice of adapting to conditions. Living beings have no absolute self; they are all influenced by conditions and actions. Their experiences of pain and pleasure both come from conditions. Even if they attain excellent rewards, things like prosperity and fame, these are effects of past causes only now being realized. When the conditions wear out, they return to nothing, so what is there to rejoice about? Gain and loss come from conditions; there is no increase or decrease in the mind. When the influence of joy does not stir you, there is profound harmony with the Way; therefore, this is called the practice of adapting to conditions.

Third is the practice of not seeking anything. Worldly people wander forever, becoming attached by greed here and there. This is called seeking. The wise realize that the principle of absolute truth is contrary to the mundane. Mentally at ease in nonstriving, physically they adapt to the turns of fate.

All existents are empty; there is nothing to hope for. Blessings and curses always follow each other. Living in the world is like a house on fire, all corporeal existence involves painwho can be at peace? Because of understanding this point, we let go of all existences, stop thinking, and seek nothing. Scripture says, Seeking is all painful; not seeking anything is bliss. Not seeking anything is clearly the conduct of the Way, so it is called the practice of not seeking anything.

Next page