One of the foremost contemporary translators of classical Buddhist and Taoist literature, Cleary has made another valuable body of work available to Western readers with this collection of writings and teachings of some of the great Zen masters of China from the ninth and tenth centuries. The Five Houses of Zen that arose at that time were not actually separate schools or branches but instead represented distinctive styles of teaching carried out by certain Chinese Zen masters and perpetuated by their students. Clearys introduction provides useful historical information on the development of Zen in China during the Tang Dynasty (619906). His translations shine with clarity and express the insights of these great teachers with beauty and understanding.

Elizabeth Salt, Library Journal

ABOUT THE BOOK

For all its emphasis on the direct experience of insight without reliance on the products of the intellect, the Zen tradition has created a huge body of writings. Of this cast literature, the writings associated with the so-called Five Houses of Zen are widely considered to be preeminent. These Five Houseswhich arose in China during the ninth and tenth centuries, often referred to as the Golden Age of Zenwere not schools or sects but styles of Zen teaching represented by some of the most outstanding masters in Zen history. The writings of these great Zen teachers are presented here, many translated for the first time. These include:

- The sayings of Pai-chang, famous for his Zen dictum A day without work, a day without food

- Selections from Kuei-shans collection of Zen admonitions, considered essential reading by numerous Buddhist teachers

- Sun-chis unique discussion of the inner meaning of the circular symbol in Zen teaching

- Sayings of Huang-po from The Essential Method of Transmission of Mind

- Excerpts from The Record of Lin-chi, a great classical text of Zen literature

- Tsao-shans presentation of the famous teaching device known as the Five Ranks

- Selections of poetry from the Cascade Collection by Hsueh-tou, renowned for his poetic commentaries on the classic Blue Cliff Record

- Yung-mings teachings on how to balance the two basic aspects of meditation: concentration and insight

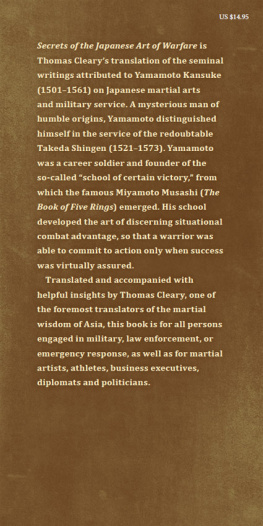

THOMAS CLEARY holds a PhD in East Asian Languages and Civilizations from Harvard University and a JD from the University of California, Berkeley, Boalt Hall School of Law. He is the translator of over fifty volumes of Buddhist, Taoist, Confucian, and Islamic texts from Sanskrit, Chinese, Japanese, Pali, and Arabic.

Sign up to receive weekly Zen teachings from Shambhala Publications.

Or visit us online to sign up at shambhala.com/ezenquotes.

SHAMBHALA PUBLICATIONS, INC.

Horticultural Hall

300 Massachusetts Avenue

Boston, Massachusetts 02115

www.shambhala.com

1997 by Thomas Cleary

Cover art: Daruma, by Fgai (15681654). Courtesy of Stephen Addiss.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The five houses of Zen/Thomas Cleary.

p. cm.(Shambhala dragon editions)

eISBN 978-0-8348-3018-9

ISBN 1-57062-292-2 (alk. paper)

1. Zen BuddhismChina. 2. Zen BuddhismQuotations, maxims, etc. 3. Priests, ZenChina.

I. Cleary, Thomas F., 1949 .

II. Series.

BQ9262.9.C5F8 1996 96-44399

294.39270951dc21 CIP

BVG 01

W HEN BUDDHISM TOOK ROOT in China after the end of the Han dynasty (206 BCE219 CE), it triggered the release of enormous waves of creative energy from a people who had been spiritually imprisoned for centuries. For four hundred years the mainstream Chinese culture had been kept within the suffocating confines of narrow-minded Confucian orthodoxy, imposed by the ruling house of Han as part of its handle on political power.

Not the least of the effects of Buddhism on China was the development of Taoism, Chinas native spiritual tradition, in highly elaborated religious and literary formats emulating the extraordinarily rich intellectual and aesthetic expressiveness of Buddhism. Yet even with the rapid expansion of Taoism, the more internationalized China of the post-Han centuries found Buddhist teachings immensely attractive, and the two religions grew side by side in the lively syncretic culture evolving in the new China.

While Buddhist literature and learning expanded the minds of the Chinese intelligentsia, Buddhist adepts took an active role in the resettlement and reconstruction of war-torn territories in the aftermath of the breakup of the old order. As relatively local and short-lived dynasties rose and fell over the following centuries, eventually Chinese warlords emulated their central Asian counterparts and began adopting Buddhism as a kind of state religion.

In contrast to Confucianism, Buddhism was an international religion, without ethnic or cultural bias. Like Druidism in pre-Roman Europe, in addition to being a repository of many kinds of knowledge, Buddhism served as a medium for international cultural and diplomatic exchange throughout most of Asia, evenperhaps especiallyin times when warfare ravaged the world at large.

There was, naturally, a drawback to the flourishing of Buddhist religion in China. As a Zen saying goes, One gain, one loss. Having become well established, well funded, and well thought of, Buddhism came to attract many idlers and many greedy and ambitious poseurs. Some sought material support, some sought intellectual diversion, some sought political power. The abundance of ritual, literature, and organizational methods that Buddhism offered was intoxicating to many Chinese aristocrats and warlords.

A result of the bewildering volume and variety of Buddhist literature pouring into China from south and central Asia was the development of schools of Chinese Buddhism based either on certain important texts or on certain arrangements of the whole body of canonical teachings. This process was already beginning by the early fifth century, and by the end of the sixth century the first syncretic school, Tien-tai, had absorbed a number of earlier schools that had been more limited in scope.

The next three centuries saw the most distinctive and most sophisticated stage of evolution, not only of Chinese Buddhism but of Chinese culture as a whole. This was the age of the Tang dynasty (619906), the zenith of the civilization and the greatest expression of its complex genius.

Tang culture was highly stimulated by the vigorous policies of the Empress Wu Tse-tien (r. 684701), a highly accomplished individual who promoted Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism to enrich the spiritual resources of the entire civilization. Discussion and debate among the three ways of thought were promoted, in order to discourage complacency under state sponsorship and bring out the best in each of the philosophies.

It was during the Tang dynasty that the Buddhist schools of Pure Land, Tien-tai, Hua-yen, Chen-yen (Mantra), and Chan (Zen) were given their definitive expression by the great masters of the age. The Pure Land school was taken to new heights of mystic experience by the ecstatic writings of Shan-tao; the Tien-tai meditation exercises were elaborately facilitated in the technical commentaries of Chan-jan; the Hua-yen universe was brilliantly illuminated in the essays of Fa-hsiang; the secrets of Tantric Buddhism were encapsulated in the esoteric art of Huikuo; and the inner mind of Chan or Zen Buddhism was straightforwardly revealed in the lectures of Hui-neng.

Next page