Mary H. Moran - Liberia: The Violence of Democracy

Here you can read online Mary H. Moran - Liberia: The Violence of Democracy full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. City: Philadelphia, year: 2013, publisher: University of Pennsylvania Press, genre: Science / Politics. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Liberia: The Violence of Democracy

- Author:

- Publisher:University of Pennsylvania Press

- Genre:

- Year:2013

- City:Philadelphia

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Liberia: The Violence of Democracy: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Liberia: The Violence of Democracy" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

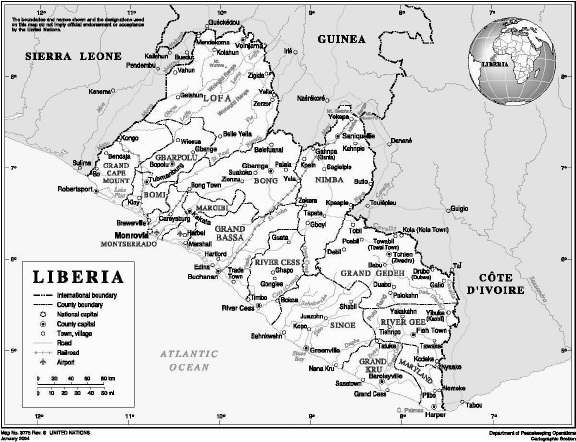

Liberia, a small West African country that has been wracked by violence and civil war since 1989, seems a paradoxical place in which to examine questions of democracy and popular participation. Yet Liberia is also the oldest republic in Africa, having become independent in 1847 after colonization by an American philanthropic organization as a refuge for Free People of Color from the United States. Many analysts have attributed the violent upheaval and state collapse Liberia experienced in the 1980s and 1990s to a lack of democratic institutions and long-standing patterns of autocracy, secrecy, and lack of transparency. Liberia: The Violence of Democracy is a response, from an anthropological perspective, to the literature on neopatrimonialism in Africa.

Mary H. Moran argues that democracy is not a foreign import into Africa but that essential aspects of what we in the West consider democratic values are part of the indigenous African traditions of legitimacy and political process. In the case of Liberia, these democratic traditions include institutionalized checks and balances operating at the local level that allow for the voices of structural subordinates (women and younger men) to be heard and be effective in making claims. Moran maintains that the violence and state collapse that have beset Liberia and the surrounding region in the past two decades cannot be attributed to ancient tribal hatreds or neopatrimonial leaders who are simply a modern version of traditional chiefs. Rather, democracy and violence are intersecting themes in Liberian history that have manifested themselves in numerous contexts over the years.

Moran challenges many assumptions about Africa as a continent and speaks in an impassioned voice about the meanings of democracy and violence within Liberia.

Mary H. Moran: author's other books

Who wrote Liberia: The Violence of Democracy? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.