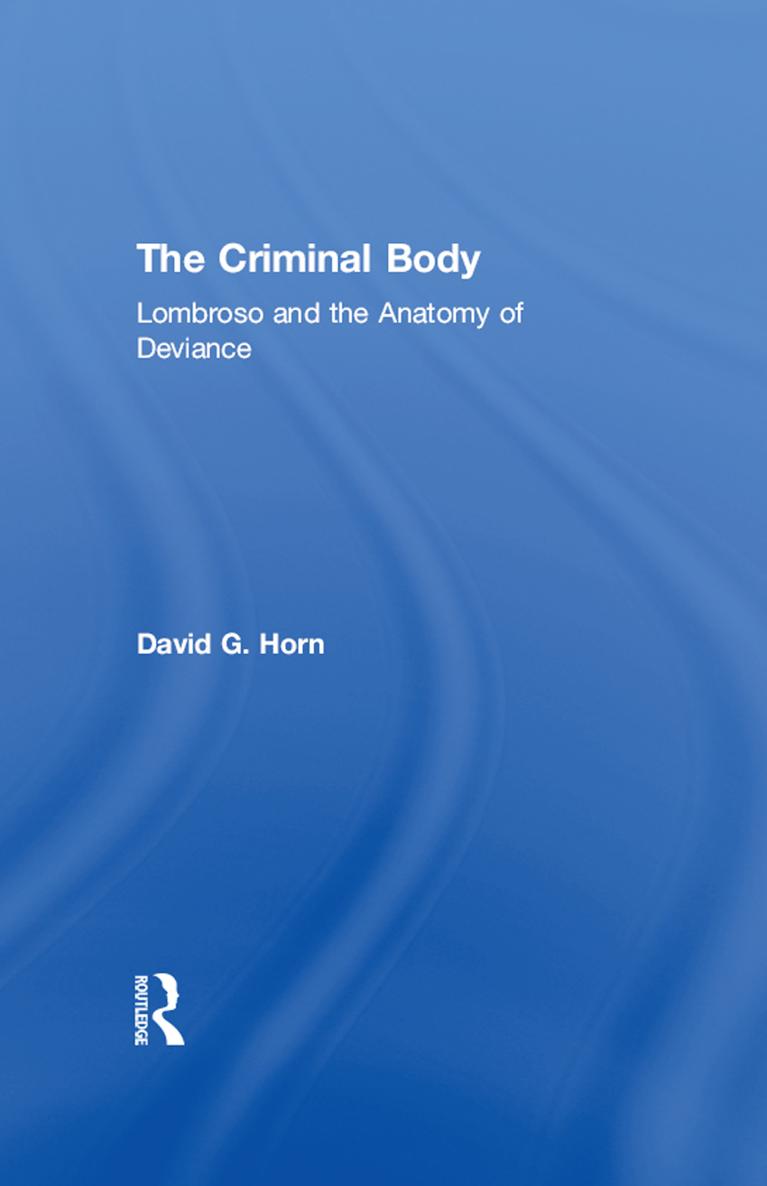

THE CRIMINAL BODY

THE CRIMINAL BODY

Lombroso and the Anatomy of Deviance

David G. Horn

Published in 2003 by

Routledge

711 Third Avenue, Published

New York, NY 10017, USA

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park,

Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 2003 by Taylor and Francis Books, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be printed or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or any other information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN 13: 978-0-415-94728-2 (hbk)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Horn, David G., 1958

The criminal body : Lombroso and the anatomy of deviance / David G. Horn,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-415-94728-6 (alk. paper)ISBN 0-415-94729-4 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Lombroso, Cesare, 18351909. 2. Criminal anthropologyHistory.

3. Criminal anthropologyItalyHistory. 4. Forensic anthropologyItalyHistory.

I. Title.

HV6035.H67 2003

364.24dc21

2003008814

For Simon and Graham

Table of Contents

I have benefited from the suggestions and critical readings of colleagues in a wide variety of disciplines over the last several years; I can only hope that I have been wise enough to heed their advice. Portions of the book were presented at conferences and workshops on Pain and Suffering in Human History (Los Angeles, 1998), on The Criminal and His Scientists (Florence, 1998), on Revolution and the Poetics of Identity (Tel Aviv, 1999), on Michel Foucault et la mdecine (Caen, 1999), and on The Italian City (London, 2000). I am grateful to the organizers for their invitations, and for the responses of Philippe Artires, Peter Becker, Luc Berlivet, Jane Caplan, Frdric Chauvaud, Daniel Defert, Elisabeth Domansky, Greg Eghigian, Gabriel Finkelstein, John Foot, Peter Fritzsche, Mary Gibson, Jan Goldstein, Igal Halfin, David Hoffmann, Peter Holquist, David Hoyt, Pierre Lascoumes, David Millet, Marcia Meldrun, Laurent Mucchielli, Ted Porter, Nicole Rafter, Francisco Vazquez Garcia, and Richard Wetzell. Ivan Crozier, Otniel Dror, Chris Forth, Jonathan Xavier Inda, Peter Redfield, Jenny Terry, Jackie Urla, and two anonymous readers provided insightful readings of sections of the manuscript.

I am grateful, too, for the patient support of my colleagues in the Department of Comparative StudiesEric Allman, Philip Armstrong, Katey Borland, Luz Calvo, Xiaomei Chen, Gene Holland, Abiola Irele, Nancy Jesser, Lindsay Jones, Tom Kasulis, Jill Lane, Rick Livingston, Margaret Lynd, Sylvia McDorman, Frank Proao, Dan Reff, Brian Rotman, Barry Shank, Maurice Stevens, Thuy Linh Tu, Hugh Urban, Julia Watson, and Sabra Webberand in the College of Humanitiesespecially Michael Hogan, Jacqueline Royster, and Chris Zacher. The research for this book was supported by a fellowship from the American Council of Learned Societies and by a Grant-in-Aid from the College of Humanities at The Ohio State University. Thanks to Ilene Kalish and Priti Gress for their interest in this project, and to Nikki Hirschman, Donna Capato, and Salwa Jabado for helping it through to completion.

Finally, thanks to Graham and Simon for being nothing like the children Lombroso imagined, and to Victoria, for her wisdom, humor, and inspiring example.

The scandalous notion of dangerousness means the individual must be considered by society at the level of his virtualities, and not at the level of his acts.

Michel Foucault, La vrit et les formes juridiques (1973)

I. Introduction: Deviant Science

This volume traces, following a variety of genealogical threads, the history of our turning to the criminal body, and of the very idea that bodies can testify (or be made to testify) to legal and scientific truths. The book is focused on nineteenth-century Italy, the site of emergence of a family of discourses and techniques intended to qualify and quantify the bodies of dangerous persons: criminal anthropology, legal psychiatry, and forensic medicine. In each field, though with some important differences, the body was made an index of the interior states and dispositions of suspected individuals, a sign of the evolutionary status of groups, and a more or less reliable indicator of present and future risks to society. Bodies were measured, manipulated, shocked, sketched, photographed, and displayed in order that judges, penologists, educators, and social planners might be guided in the identification and treatment of individuals, and in the development of appropriate measures of social prophylaxis.

This book participates, a full century later, in a renewal of interest in the body-as-evidence, but seeks to problematize this fascination (in the academy, in the laboratory, and in courts of law) by writing its history. Neither a comprehensive account of Italian social sciences, nor a biographical study of their founders, it is organized around particular kinds of worrying over, interrogation of, and faith in the body. It aims, in this way, to make provisional sense of our continued efforts to generate truths from the surfaces and depths of bodies. At the same time, this book is intended as a contribution to historical and cultural studies of science. It works to situate sciences of deviance (and the practices and technologies these engendered) in particular historical and cultural contexts, and to read sciences now marked as illegitimate or pseudoscientific in relation to those that have become canonical (evolutionary biology, physiology, biological anthropology, ethnography.) Only such a blurring or transgressing of comfortable boundaries makes it possible, for example, to locate criminal anthropology in relation to the emergence of new reading practices (penile plethysmography, facial thermography, PET scans, the decoding of the human genome) that seek to make human difference and dangerousness legible.

With rare exceptions, Italian criminal sciences have not figured in the origin stories anthropologistseven Italian anthropologistshave told about themselves.

Criminal anthropology has not fared much better in the discipline of history of science, which has not found it worthy even of the attention given to alchemy, astrology, or phrenology. Instead, criminal anthropology has been limited to a supporting role in a cautionary tale about deviant or spurious science; it has been invoked either to make visible the differences between impure and pure ways of knowing, or else to reassure us of the ability of real science to police its borders or to straighten the path to truth. The most familiar account to English

Finally, within social history, the work of Italian anthropologists has been positioned as fundamentally at odds with ethnographic and sociological approaches to crime and other social phenomena, particularly as these developed in France. This binary was first established in debates between the Italian and French schools of criminology at the end of the nineteenth centurylargely at a series of international conferencesbut has been reinforced by the historiography of the 1970s and 1980s.