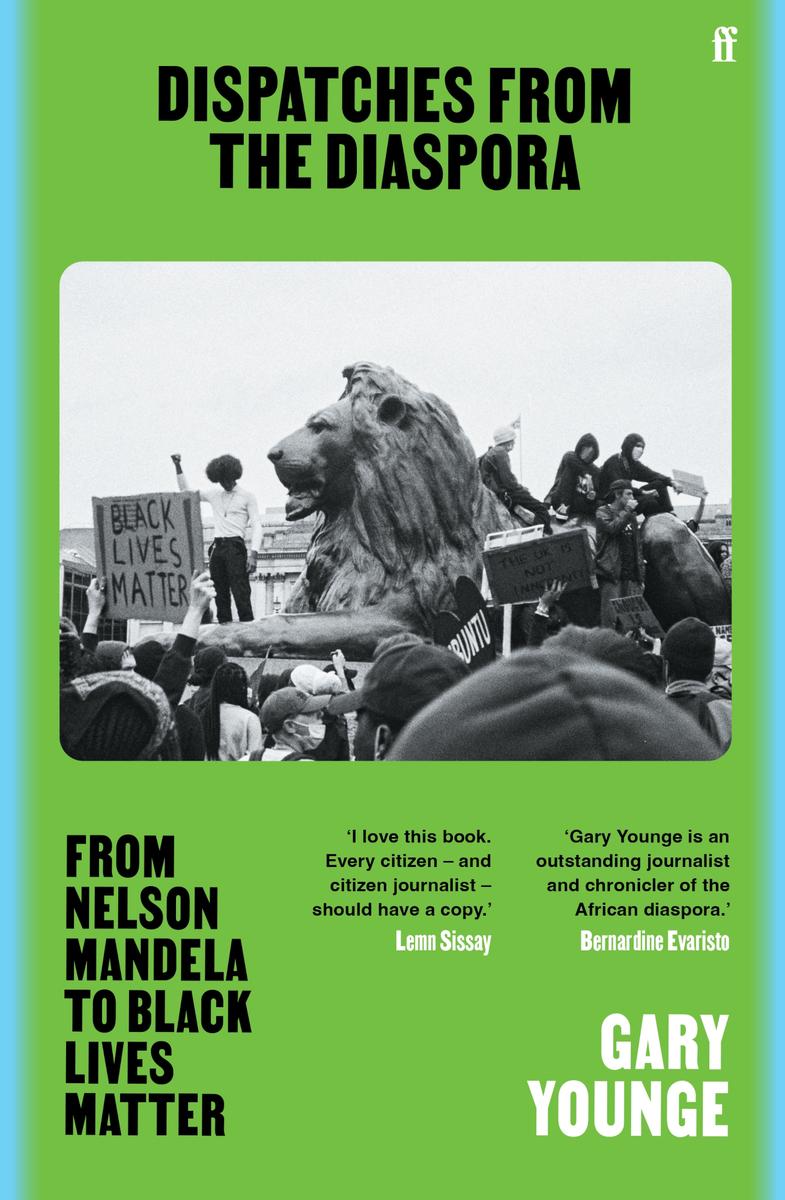

The night before South Africas first democratic elections I slept at the home of a family in Soweto so I could accompany them to the polls the next day. A thick fog hung low over the township that morning that was only just beginning to lift as they set off to vote. Beyond those closest to you all you could see were shoes and trouser hems, the number of ankles growing with every step and every block as more joined us on our way to the polling station. Dressed in Sunday best, nobody was talking. Nelson Mandela had described his political journey as the long walk to freedom. This was the final march.

It was a huge day for me personally. As a seventeen-year-old I had picketed the South African embassy in Trafalgar Square with my mother, calling for Mandelas release; as an eighteen-year-old I had set up an anti-apartheid organisation at my university in Scotland. And now here I was, watching the mist burn on the moment.

But it was important for me professionally too. The Guardian had sent me to South Africa, aged twenty-four, to try and get some of the stories white journalists couldnt get. I had stayed in Alexandria township for several weeks, and travelled to Moria, near Polokwane, in a minibus with members of the Zion Christian Church for their Easter pilgrimage. But my main assignment had been to follow Mandela on his campaign trail.

There was just one catch: I couldnt drive. Mandelas campaign took him to far-flung areas of a country with precious little public transport. To get the job done I had to organise an elaborate network of favours. I got lifts to rallies with journalists, paying for their petrol and keeping them company. Once there, I would then ask if anyone was heading back to the nearest big town and do the same again. During one of those trips a film crew dropped me off at a petrol station and told me theyd arranged for others to take me the rest of the way. The people who picked me up were Mandelas bodyguards. We got chatting. They found me amusing (more accurately put, I made it my business to amuse them). We had things to talk about. I had studied in the Soviet Union (my degree was in French and Russian), as had many of them; I had been involved in the anti-apartheid movement; and I was from England, where a number of them had spent some time in exile. They let me hang around with them on a regular basis.

So there I was, an occasional extra in Mandelas extended entourage, with a ringside seat on history. The trouble was, I still had to write the article. It was to occupy the most coveted slot in the paper at the time, and I felt the pressure keenly. Just a day before I had to file I was still lost in the piece and couldnt pull the various strands together. Id never felt so out of my depth.

I gave it to David Beresford, the Guardians senior correspondent in South Africa at the time, who went through it slowly, giving precious little away. He handed it back with & signs where he thought I should expand it and signs where I should shorten it. Its all there, he said. There are some wonderful bits. But youve been working on it so long you cant see them. You need to take a break from it. I had to file it the next day. Lets go and get something to eat, he said, and talk about something else, and then you work on it overnight, and itll be great.

I dont know if he really believed that. But I didnt. I spent all night on it, moving things around, chopping bits out and adding information elsewhere, as hed suggested. When morning came, I sent it over to the paper, convinced I had delivered an incoherent mess and that the notion of sending a young Black journalist to cover a huge story would be forever tarnished. Then I headed for Soweto to stay with a family for the night before going to the polls with them.

Communications back then were relatively basic. I didnt have a mobile phone, so I had no idea how the piece had been received. I spent the day with the family in Soweto as they went to vote. It was only when I went to file that story that I began to receive a number of internal messages, each one coming up separately on my computer, as though on ticker tape: first peers, then desk editors, then the deputy editor and finally the editor (a first), all complimenting me on the article. And so it was that I sat in a house in Soweto with my eyes welling up, feeling a mixture of relief, accomplishment and regret that my mother, who had stood alongside me on those night-time pickets, was not there to read it.

This was the article that launched my career, and within a few months I was offered a staff job at the Guardian as assistant foreign editor. It wasnt the career path I had anticipated. Originally I had wanted to be the Moscow correspondent. But in 1996 I was awarded the Laurence Stern Fellowship, which sends one young British journalist to the Washington Post every year to work for a summer on the national desk. I fell in love with an American. Within three years I had written a book about travelling through Americas Deep South; within seven I was the Guardians New York correspondent.

This book is a collection of pieces written during that twenty-eight-year-long journalist career, almost half of which I spent in the US. Most are from the Guardian, where I spent twenty-five of those years, before becoming a professor at the University of Manchester. But roughly a quarter of them are not. For much of that time I have been the Alfred Knobler Fellow at the Type Media Center based in New York and have written regular articles for The Nation magazine. The collection also includes work from The New Statesman, GQ, the New York Review of Books and the Washington Post.

Over the span of my career I have covered six UK general elections, seven US presidential elections, the Occupy Wall Street movement, the Tea Party and Brexit. I have reviewed books, films and television shows and commented on the wars in Bosnia, Iraq and Libya, the Arab Spring, migration, gay rights, terrorism, Islamophobia, feminism, anti-Semitism, economic inequality, social protest, guns, knives, nuclear weapons, the Roma in Eastern Europe, Latinos in America, Turks in Germany and Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland. I have examined the impact that McDonalds apple dippers will have on the agricultural sector and why children love spaghetti.

This collection does not draw from all the articles I have written, but only those from or about the African diaspora, including the Caribbean, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone and Europe, as well as Britain and the US. This is a path that, from the very outset, I was warned not to take. To become too identified with issues of race and racism (Black people, basically) would, some said, find me pigeon-holed.

This advice, which came from older white journalists (pretty much the only older journalists available when I started out), was rarely malicious. They thought they were looking out for me. A fear of being pigeon-holed is one of the most common crippling anxieties of any minority in any profession. Being seen only as the thing that makes you different through the lens of those with the power to make that difference matter really is limiting.

Then there were other, older, white editors who wanted me to write only about race. One of the first columns I wrote for the