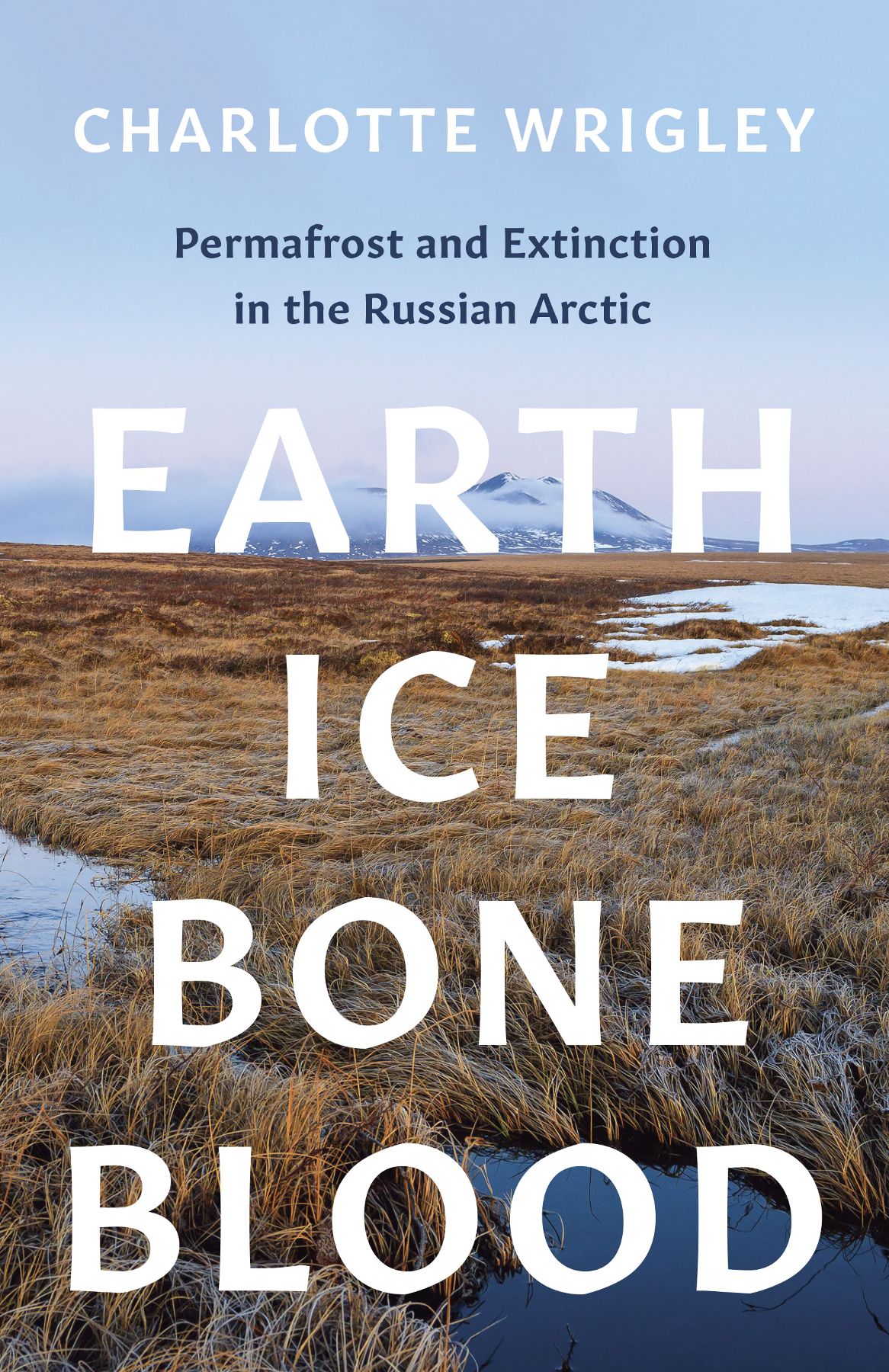

Earth, Ice, Bone, Blood

Earth, Ice, Bone, Blood

Permafrost and Extinction in the Russian Arctic

Charlotte Wrigley

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

The University of Minnesota Press gratefully acknowledges the generous assistance provided for the publication of this book by the Hamilton P. Traub University Press Fund.

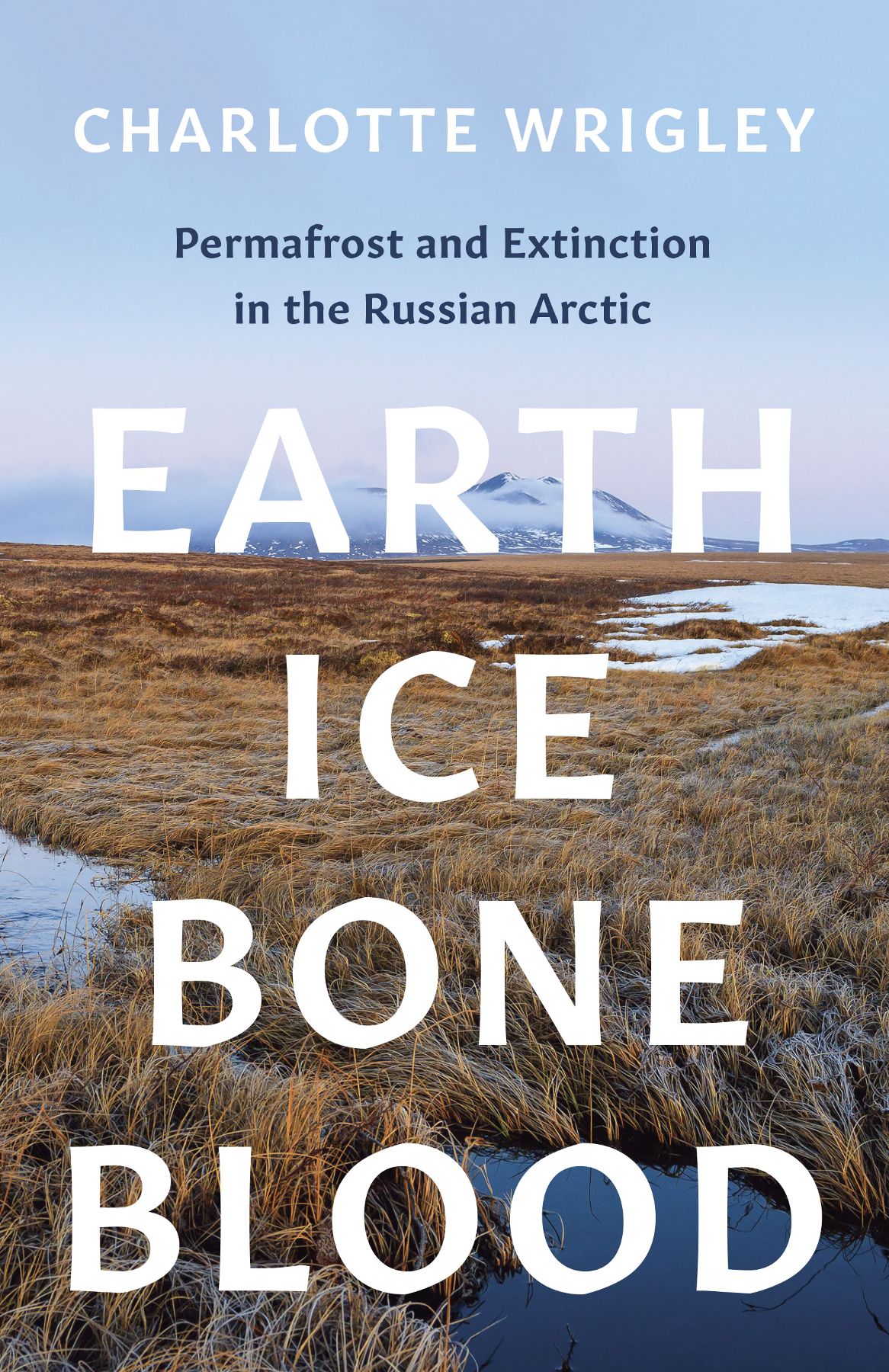

Cover design by Catherine Casalino

Cover photograph: Andrew Stepanov, stock.adobe.com

Portions of chapters 2 and 4 are adapted from Ice and Ivory: The Cryopolitics of Mammoth De-extinction, Journal of Political Ecology 28, no. 1 (2021): 782803. https://doi.org/10.2458/JPE.3030.

Illustrations, unless otherwise specified, were photographed by the author.

Copyright 2023 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

ISBN 978-1-4529-6898-8 (ebook)

A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress.

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

Contents

On the four-hour plane journey from Yakutsk to the Arctic port of Chersky, the landscape changes visibly. The June weather in Yakutsk, the capital of the Russian region of the Sakha Republic, is hot and dusty. Peering through the dirty windows of the Soviet-era Antonov An-24 turboprop plane, I start to notice the ground turn white as we head northward. Then come the mountainsvast stretches of earth crinkled like brain tissue, like balls of paper. As we get closer to the Arctic, the mountains make way for tundra dotted with hundreds of oxbow lakessomething that would have made my high school geography teacher very happy. The plane almost skims the frozen surface of the Kolyma River as it makes its descent toward Cherskys airport. Upon landing, the Russian border guards check the passengers permits, and we are allowed to disembark. I can feel the Northness. Up here, the air is fresh and bitingly cold, the sun pale and milky against a hazy sky. There is silence over the Kolyma, punctured only by the scream of a kittiwake and the chattering of families reunited on the runway. The ground is hard, but otherwise there is little to indicate that beneath my feet lies frozen permafrost several hundred meters thick.

A few days later, I accompany the science stations resident botanist, Sergei Davidov, to tend to his Arctic garden. Its early June and theres nothing therejust frost and frozen soilbut he tells me the names of all the flowers that will push through in the coming weeks. He tells me the climate is changing. As a keen birder, he has noticed a shift in the migration patterns of birds; the pin-tailed snipe now makes its nest on the tundra, when it never used to before. I can scarcely believe that such a cold, gray place will burst into life, but it does: just over a week later the hill is a riot of colors, purple, yellow, blue, and pink, as stubby little flowers have taken root quickly in the thawing permafrost topsoil. Ice from the Arctic Ocean drifts in thick slabs down the Kolyma, carrying with it the trunks of giant pine trees and flooding the lower parts of the town. When I walk into the tundra, the ground is marshy and my boots get saturated with mud and icy water. It never gets dark, and the mosquitoes feast on my blood.

When a large group of American permafrost scientists arrive in Chersky, I go with them to their field sites around the science station. There are a number of controlled-burn sites in the larch forests near Chersky, and the group is here to check on them and see what has colonized the patch of soil since the previous season. It is almost oppressively hot at this point of the Arctic midsummer. The leader of the group, Heather Alexander, cuts into the earth in a neat square shape to produce a permafrost brownie that clearly shows the layers of moss, organic matter, and mineral soil that form the permafrost active layer (the part that thaws in the summer). The permafrost in the forest is a little more robust than that on the tundra because of the larch roots that stabilize the ground, but there are patches of waterlogged mire here and there. Theres a video (unfortunately, impossible to reproduce in these pages) that shows the team members bouncing on the permafrost as if on a trampoline made of jelly. Throughout my time in Chersky, I witnessed the permafrost earth changing rapidly: freeze to thaw, solid to liquid, continuous to discontinuous.

I was the first scholar from the social sciences and humanities ever to visit the North-East Science Station and the Pleistocene Park in Chersky. I mention this not to blow my own trumpet but rather to highlight both the rarity and the importance of doing critical Arctic fieldwork when so much of what is reported on this region in the global popular media tends toward hyperbole and reinforces stereotypes. Access and ability to conduct this fieldwork is a thorny topic, underscored by inequity in funding opportunities and geopolitical boundary-making practices, much of which privileges Western institutions. The vast majority of visitors to the Pleistocene Park are Western scientists with large grants who are able to afford the $250 a day it costs to stay there and journalists who visit for a few days at a time to write or film short pieces that perpetuate the myth that the Arctic is empty and wild. While my own visit of a month was curtailed by limited funding and access (the station operates only during the summer), becoming immersed in both the practices of permafrost science and the daily rhythms of permafrost living was integral to my understanding of how permafrost as an object is constructed by the different agencies and motivations of those who engage with it. How permafrost is presented is often shallow, barely scratching the surface, treating permafrost as a repository for more interesting things. Digging deeper necessitates standing in the soil, noticing the smaller but no less important ways permafrost affects and is affected by the humans and nonhumans that live with it.

Yakutsk is the largest city in the world built on permafrost, but it is not the only one. The Arctic is a social space, and one that resists the colonial narrative of empty, barren wastelands ripe for exploration and discovery. Sakha, despite having a population roughly the size of Belgiums spread across a region the size of India, is dotted throughout with towns and villages; the traces of living on and with permafrost are everywhere across the Russian Arctic, but it is important to recognize also how the permafrost produces the Sakhan landscape. Yakutsk, once a place of pioneering permafrost science and impressive permafrost infrastructure, now seems skewed. Some buildings sport cracks; some even collapse. The roads are no longer straight, nor are the pipelines, streetlights, and road signs. I wanted to understand what it is like to live in a permafrost city, if only briefly. The Melnikov Permafrost Institute invited me for a stint as a visiting scholar, so I spent the winter of 2018 living and working in Yakutsk, watching the first snows fall in October and the river gradually freeze over into an ice road. Climate change seems a long way off in temperatures that can plummet to minus 50 degrees Celsius, but it makes itself known in the encroaching decay of the city and the lack of funding available to the government of Sakha to make repairs. My adopted colleagues at the MPI have had their research similarly scuppered by poor funding from the Russian Academy of Sciences. I spent my days in their company, learning about their work and their frustrations, becoming aware of the disconnect between the institutes Soviet history and its current state. Their science is different in type from the rather more ad hoc and responsive work done at the science station in Chersky, and it also reveals the discrepancy in funding between Russian permafrost scientists and Western ones. Addressing both issues through an interrogation of how science produces truths and norms is key to understanding the trajectory of permafrost science and the varying responses to climate changeinduced permafrost thaw.

Next page