Table of Contents

There was a whispering in my hearth,

A sigh of coal,

Grown wistful of a former earth

It might recall.

I listened for a tale of leaves

And smothered ferns,

Frond-forests, and the low sly lives

Before the fawns.

Wilfred Owen, Miners

Beginnings

Natural History Museum, London

An albatross dips towards the sea, then lifts again, beating its wings as if repelled by the opposing magnetism of the water. At first, nothing else stirs. The sea is deathly calm, spread out like a cerecloth. Then a giant rocketing breath hurls a rainbow into the air. As the whale arches and begins to descend under water, the dimpled grey of its back turns into the blue sheen which earned it its name. I see the whale more completely in my imagination. In reality, each sight of it is a jigsaw piece. The whale is simply too huge to be viewed in its entirety. It disappears and, moments later, surfaces at a great distance, its blows sounding notes of both discontent and deliverance.

Watching the blue whale that day, I questioned what it was that I hoped to capture in writing this book. I had been travelling for several months through the southern waters where the blue whales live, determined to understand why these and other marvels of nature were imperilled and why that should matter. Reflecting on the dreamlike moment of the creatures fleeting show, I saw myself as a child again, staring up at a model of a blue whale suspended from the ceiling of a museum.

I first visited the Natural History Museum in London when I was about nine or ten. The architect, Alfred Waterhouse, scaled the building to the dream of diversity, its curves decorated with Daedalian sculptures of living and extinct forms of life. It was a panorama of metamorphosis, a treasury of the wonders of how life evolved and the sobering realities of how life could end. In the alcoves and galleries that lined the echoing building like confessionals were the serried remains of extinctions. The guttered brow of a Neanderthal skull, the bevelled flint tools of early human ambition. Beyond these, the brittle silhouette of Archaeopteryx lithographica, the feathered and fearsomely toothed strange bird crucial to Darwins defence of evolution. The palaeontologists of the previous generation were convinced that the entire class of birds sprang suddenly into existence, whereas the discovery of the first archaeopteryx fossil gave evidence of their painstaking transition from carnivorous dinosaurs. The ancient bird lived on the Earth 150 million years ago, its wings tipped by two large claws, its body flaunting a long lizard-like tail. The discovery of this beast, Darwin wrote, proved more forcibly than nearly any other find how little his generation knew about the Earths former inhabitants.

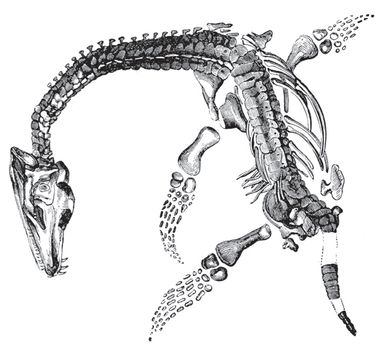

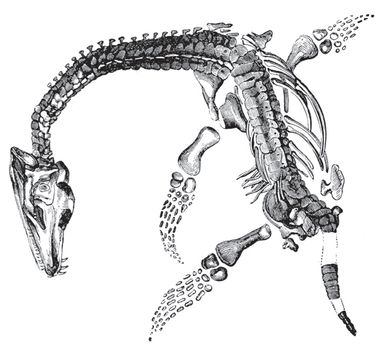

Near to a display of the armoured anatomies of trilobites was an ichthyosaur skeleton scoured from its hiding place in beds of shale by Mary Anning, the fossil-hunter who gained notoriety in the nineteenth century for several spectacular finds. She kept her family from debt by hawking the remains of extinct life in her glass-fronted shop in the English seaside resort of Lyme Regis. She was led to her profession by a local character called Captain Cury, the curiosity-man who stole on to the coaches that stopped at Lyme Regis on passage between London and Exeter. He touted fossils given fashionable names to make them more appealing to female clients: Ladies fingers, Crocodiles backs, John Dories petrified mushrooms. After her father fell to his death from nearby cliffs, Mary began rummaging around the seashore in search of her own curiosities. She was only ten years old when she sold her first ammonite to a wealthy lady for half a crown.

There were the grey splintered remnants of a toxodon. On the voyage of the Beagle, Darwin and his companions witnessed the unearthing of one of these, perhaps one of the strangest animals ever discovered. A native of South America, the flexed bow of its teeth was like that of a rabbit, while the angles of its eyes, ears and nostrils seemed to ally the giant animal with the manatee. Beyond the toxodon, there was a skeleton of Mammut americanum, scraped out of the dusts of Missouri, its tusks trained upwards like bugles to the skies. Ceiling panels depicted plants both day-to-day and exotic. These gilded illustrations reflected an era when the flowering world was a source of sentimentality and fascination. As specimen-collectors brought seeds and cuttings from all around the world, the wealthy of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries rushed to embellish their gardens with striking and tropical species, while glasshouses and public parks opened up to exploit their new fancy. Some imported plants became widespread, while other species became rare, their delicate replicas floating above the exhibits as memories of an old season.

I visited the museum again not long before beginning my travels, a nostalgic retracing of youthful fascination. The sturdy wreaths of a diplodocuss vertebrae patterned the floor like footprints mocking its former animation. The fogged glass of the windows filtered the winter sunlight. It shrouded the hall in a cadaverous yellow. A knot of schoolchildren muscled one another for a peek at one of the oddest animals in the hall, the glyptodon, a giant armadillo most probably hunted to extinction by humans thousands of years ago in South America. The beasts small mouse-like head and tail like a huge ice-cream cone softened the ferocity of its bulging hauberk. The children chattered together about the possible revival of such monstrous forms. We can bring them to life again, they said. We can make a zoo of monsters!

In the shadows of the museum, the brooding shapes of earlier creations unsettled the assurances of our tangible human world. It was here that I first encountered the slightness of human life. Beneath the magnetic appeal of the giant creatures and plants was a terrifying suggestiveness, the millions of years since their demise. Looking at them with a childs eyes, I experienced a kind of mental vertigo at the abyssal distances that lie before and after our brief lives. It was akin to the rising sickness I sometimes felt while lying awake in the darkness, contemplating the existence of my parents before the arrival of me and my sister.

Darwin described a related vertigo on encountering the giant mammals that once inhabited South America. How might one reflect on the Americas without a sense of disbelief and awe, he asked, when formerly the continent swarmed with great monsters? Darwins theories on how the diversity of life on Earth arose fortified an old idea that something larger than our own reality haunted us. The idea was there in the ancient Greek myth of the Hekatonkeires, three colossal beings with a hundred hands each, who ruled the world at the beginning of time. These giants were the offspring of earth and oceans, their spirits expressing themselves as forces of nature in earthquake, hail, storm and eruption. Those who came in their wake eventually conspired to banish them, fearing as they did their volatile powers.

But the chief touchstone of my awakening to extinction hung in the Large Mammals Hall, built in 1934 to house the skeleton of a blue whale that beached on the shores of Irelands Wexford Bay at the close of the nineteenth century. Below its bones, strung in the air as an aide-memoire to mortality, was a full-size model of the whale. Each time that I visited the museum, I nagged my father to take me back to the exhibit. The blue whale, in large part due to its gigantic proportions, had become an obsession of mine. Entering the hall, I stared across this colossus of saxe-blue flesh and the perspective of bone pinioned to the ceiling, the air transmuted to ocean. Over the years, I never tired of the exhibit. Only when my sensibilities matured to adulthood did I begin to shrink from it. I saw it now as a harbinger of extinction, one of the museums