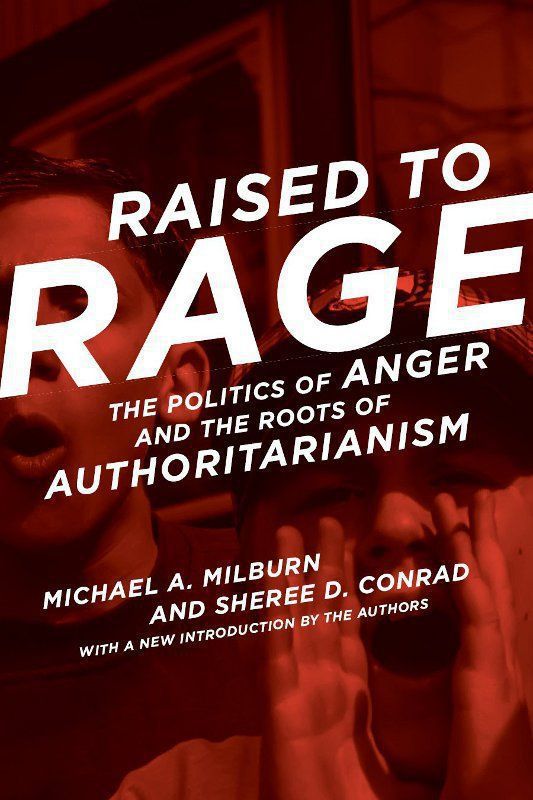

Raised to Rage

Raised to Rage

The Politics of Anger and the Roots of Authoritarianism

Michael A. Milburn

Sheree D. Conrad

The MIT Press

Cambridge, Massachusetts

London, England

2016 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

Originally published as The Politics of Denial

1996 Massachusetts Institute of Technology

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by any electronic or mechanical means (including photocopying, recording, or information storage and retrieval) without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book was set in Sabon. Printed and bound in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-0-262-53325-6

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to my parents,

Thomas Milburn and JoAnne Milburn

M.A.M.

And to the memory of

David R. Mariani

S.D.C

Contents

This book would not have been possible without the help, advice, and support of a number of people. We want to thank our agent, Elizabeth Ziemska, for her support and enthusiasm, for believing in the project from the beginning, and for her very valuable suggestions about the content. We also want to thank Amy Pierce at the MIT Press, who brought great enthusiasm and commitment to the project and helped us to write a much better book.

The research of several of our students at the University of Massachusetts/Boston contributed tremendously to this volume, particularly Fabio Sala, Sheryl Carberry, Ron Levine, Anne McGrail, Patricia Casimira, and James Hopper.

Both Michael Lustig and Eric Webster worked tirelessly to gather primary materials for the text. They contributed insight and understanding to the research they did for this book, and it would never have been finished on time without their help. Thanks also to several other student assistants, Tomas Kavaliauskas, Suzanne DAllessandro, Don Masterson, and Tom Gilmore, for their help with research on the book. Natalie Zacek did extensive research for .

Michael Laurie read early drafts of several chapters and provided valuable feedback. Marshall Cohen, Kathy Kraft, and Dianne Horgan read the entire manuscript and gave very important suggestions for changes, Peter Milburn provided important research assistance for . Thanks for their help to Douglas Hodgkin, Simon Jackman, Brad Jones, Scott Keeter, Taeku Lee, Bill Kubik, Robert Yale Shapiro, Eric R. A. N. Smith, and other members of POR, the public opinion research Internet discussion group. We also want to thank our colleagues, Dennis Byrnes and Don Kalick, for their ongoing support.

Sheree Conrad gives thanks to Elizabeth ONeill, Mary Kohk, Nancy Corbin, and Sheila Purdy for their love and support and also to her family, Thelma Dukes, and Diane, Steven, Alissa, Abby, and Aime Bourque.

Michael Milburn thanks his daughters, Allison, Johanna, and Abby, for their support and forbearance during this project. His wife, Deborah Kelley-Milburn, deserves a special mention. Not many scholars have the extreme good fortune to be married to a highly skilled Harvard University reference librarian and expert on electronic databases and the Internet. Luckily for Dr. Milburn, he is one of those fortunate scholars. In many, many ways, this book would not have been completed without her. It probably would never have been started, either.

Material from Spare the Child by Philip Greven, Jr., copyright 1990 by Philip Greven, Jr., is reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. Excerpts from For Your Own Good by Alice Miller, translated by Hildegarde and Hunter Hannum, translation copyright 1983 by Alice Miller, are reprinted by permission of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, Inc., and by Faber & Faber, Ltd. Excerpts from the article The Killing Trail by H. G. Bissinger, which originally appeared in Vanity Fair, are reprinted with permission of William Morris Agency, Inc., as agent for H. G. Bissinger, 1995 by H. G. Bissinger. Material from The Ego and the Mechanisms of Defense by Anna Freud, 1966, is reprinted by permission from International Universities Press, Inc.

Twenty years ago, with the publication of The Politics of Denial , we presented our initial research supporting what we now call affect displacement theory. Our results suggested that attitudes toward some political issues might be determined, in part, by emotion rather than reason. We found, specifically, that men with a history of being brutalized in childhood seemed to both deny the pain of their own experience and their anger at the perpetrators, while simultaneously displacing that anger onto political issues that involved an element of punishmentthe death penalty, the use of military force, punitive policies toward women seeking abortionsattitudes with a large symbolic component of power, toughness, and retribution (Milburn and Conrad 1996). Of course, not all conservatives who hold these attitudes have a history of childhood mistreatment, and not all conservative issues attract the same degree of emotionit is particularly those issues that offer a perceived opportunity for retribution against those seen as transgressing social norms and moral imperatives.

The glorification of toughness is typical of individuals who hold the views and display the traits of authoritarianism, a personality type first identified by researchers studying anti-Semitism following World War II. Authoritarianism develops from rigid, punitive childrearing and involves denial of the reality of harsh, even terrifying parents and of ones own anger toward them coupled with displacement of that anger onto despised minorities in the society. This unforgiving rage toward out-groups grows in times of heightened stress from real social and economic instability.

Our model helps to explain a paradox in U.S. public policy: although prevention works much better than punitiveness does in solving problems, punitive policies have generally succeeded at the polls for the last thirty years. The displacement of anger, in some cases triggered by real economic and social instability, influences public support for punitive public policies, and we have seen many politicians who have been willing to exploit punitiveness in their campaign rhetoric and policies, using scapegoating and exaggeration of danger, and leading to support of punitive public policies such as mandatory sentencing, three strikes and youre out, carpet bombing the Middle East, and the targeted killing of the families of terroristsa war crime.

A related question that motivated our work is, How are people brought to vote against their own economic self-interestbehavior that seems quite irrational? Understanding affect displacement, the roots of authoritarianism, and the way politicians tap triggered emotion all helps provide an answer to this question. In the twenty years since The Politics of Denial was published, there has been a resurgence of interest in and research on the damaging effects of authoritarianism, including Marc Hetherington and Jonathan Weilers (2009) book Authoritarianism and Polarization in American Politics. They found a strong relationship by state between support for George W. Bush in the 2004 election and approval for the use of various forms of physical punishment for children, both factors, Hetherington and Weiler argued, reflecting authoritarianism. They correctly linked authoritarianism and punitive child-rearing. Our research goes further and connects these two variables causally.

It is important to acknowledge that the politics of denial is one of many processes that influence public opinion and political behavior. Nevertheless, we argue that nonconscious influences do play a crucial and generally overlooked role. The research we have conducted over the past two decades has supplied further support for our contentions about affect displacement and the politics of denial, as has research done by other social scientists. In addition, current research in cognitive neuroscience, some of which we describe below, has done much to elucidate the biological foundations of the work on social attitudes and authoritarianism we present here.