The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To those who knew neither thee nor me, yet suffered for us anyway

But pardon, gentles all,

The flat unraisd spirits that hath dared

On this unworthy scaffold to bring forth

So great an object. Can this cockpit hold

The vasty fields of France?

Shakespeare, Henry V, Prologue

C ONTENTS

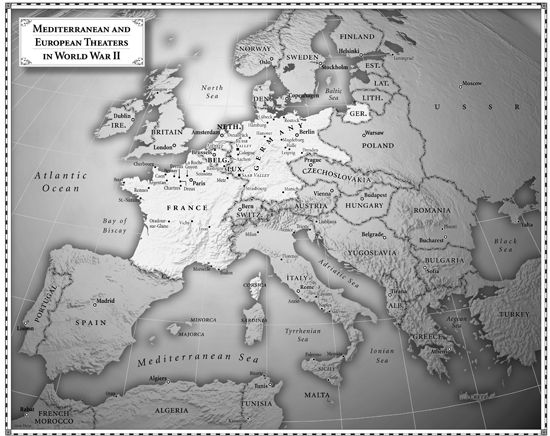

M APS

P ROLOGUE

A KILLING frost struck England in the middle of May 1944, stunting the plum trees and the berry crops. Stranger still was a persistent drought. Hotels posted admonitions above their bathtubs: The Eighth Army crossed the desert on a pint a day. Three inches only, please. British newspapers reported that even the king kept quite clean with one bath a week in a tub filled only to a line which he had painted on it. Gale winds from the north grounded most Allied bombers flying from East Anglia and the Midlands, although occasional fleets of Flying Fortresses still could be seen sweeping toward the Continent, their contrails spreading like ostrich plumes.

Nearly five years of war had left British cities as bedraggled, unkempt and neglected as rotten teeth, according to an American visitor, who found that people referred to before the war as if it were a place, not a time. The country was steeped in heavy smells, of old smoke and cheap coal and fatigue. Wildflowers took root in bombed-out lots from Birmingham to Plymouthsow-whistle, Oxford ragwort, and rosebay willow herb, a tall flower with purple petals that seemed partial to catastrophe. Less bucolic were the millions of rats swarming through three thousand miles of London sewers; exterminators scattered sixty tons of sausage poisoned with zinc phosphate, and stale bread dipped in barium carbonate.

Privation lay on the land like another odor. British men could buy a new shirt every twenty months. Housewives twisted pipe cleaners into hair clips. Iron railings and grillwork had long been scrapped for the war effort; even cemeteries stood unfenced. Few shoppers could find a fountain pen or a wedding ring, or bedsheets, vegetable peelers, shoelaces. Posters discouraged profligacy with depictions of the Squander Bug, a cartoon rodent with swastika pockmarks. Classified advertisements included pleas in the Times of London for unwanted artificial teeth and cash donations to help wounded Russian war horses. An ad for Chez-Vous household services promised bombed upholstery and carpets cleaned.

Other government placards advised, Food is a munition. Dont waste it. Rationing had begun in June 1940 and would not end completely until 1954. The monthly cheese allowance now stood at two ounces per citizen. Many children had never seen a lemon; vitamin C came from turnip water. The Ministry of Food promoted austerity bread, with a whisper of sawdust, and victory coffee, brewed from acorns. Woolton pie, a concoction of carrots, potatoes, onions, and flour, was said to lie like cement upon the chest. For those with strong palates, no ration limits applied to sheeps head, or to eels caught in local reservoirs, or to roast cormorant, a stringy substitute for poultry.

More than fifty thousand British civilians had died in German air raids since 1940, including many in the resurgent Baby Blitz begun in January 1944 and just now petering out. Luftwaffe spotter planes illuminated their targets with clusters of parachute flares, bathing buildings and low clouds in rusty light before the bombs fell. A diarist on May 10 noted the great steady swords of searchlights probing for enemy aircraft as flak fragments spattered across rooftops like hailstones. Even the Wimbledon tennis club had been assaulted in a recent raid that pitted center court; a groundskeeper patched the shredded nets with string. Tens of thousands sheltered at night in the Tube, and the cots standing in tiers along the platforms of seventy-nine designated stations were so fetid that the sculptor Henry Moore likened wartime life in these underground rookeries to the hold of a slave ship. It was said that some young childrenperhaps those also unacquainted with lemonhad never spent a night in their own beds.

Even during these short summer nights, the mandatory blackout, which in London in mid-May lasted from 10:30 P.M. to 5:22 A.M. , was so intense that one writer found the city profoundly dark, like a mental condition. Darkness also cloaked an end-of-days concupiscence, fueled by some 3.5 million soldiers now crammed into a country smaller than Oregon. Hyde and Green Parks at dusk were said by a Canadian soldier to resemble a vast battlefield of sex. A chaplain reported that GIs and streetwalkers often copulated standing up after wrapping themselves in a trench coat, a position known as Marble Arch style. Piccadilly Circus is a madhouse after dark, an American lieutenant wrote his mother, and a man cant walk without being attacked by dozens of women. ProstitutesPiccadilly Commandossidled up to men in the blackout and felt for their rank insignia on shoulders and sleeves before tendering a price: ten shillings (two dollars) for enlisted men, a pound for officers. Or so it was said.

Proud Britain soldiered on, a bastion of civilization even amid wars indignities. A hurdy-gurdy outside the Cumberland Hotel played You Would Not Dare Insult Me, Sir, If Jack Were Only Here, as large crowds in Oxford Street sang along with gusto. Londons West End cinemas this month screened For Whom the Bell Tolls, starring Gary Cooper and Ingrid Bergman, and Destination Tokyo, with Cary Grant. Theater patrons could see John Gielgud play Hamlet, or Nol Cowards Blithe Spirit, now in its third year at the Duchess. At Ascot on Sunday, May 14, thousands pedaled their bicycles to the track to watch Kingsway, a colt of the first class, gallop past Merchant Navy and Gone. Apropos of the current cold snap, the Royal Geographical Society sponsored a lecture on the formation of ice in lakes and rivers.

Yet nothing brightened the drab wartime landscape more than the brilliant uniforms now seen in every pub and on every street corner, the exotic military plumage of Norwegians and Indians, Belgians and Czechs, Yorkshiremen and Welshmen and more Yanks than lived in all of Nebraska. One observer in London described the panoply:

French sailors with their red pompoms and striped shirts, Dutch police in black uniforms and grey-silver braid, the dragoon-like mortar boards of Polish officers, the smart grey of nursing units from Canada, the cerise berets and sky-blue trimmings of the new parachute regiments gaily colored field caps of all the other regiments, the scarlet linings of our own nurses cloaks, the electric blue of Dominion air forces, sand bush hats and lion-colored turbans, the prevalent Royal Air Force blue, a few greenish-tinted Russian uniforms.

Savile Row tailors offered specialists for every article of a bespoke uniform, from tunic to trousers, and the well-heeled officer could still buy an English military raincoat at Burberry or a silver pocket flask at Dunhill. Even soldiers recently arrived from the Mediterranean theater added a poignant splash of color, thanks to the antimalaria pills that turned their skin a pumpkin hue.

Next page