Dedicated to

Anita and Hari

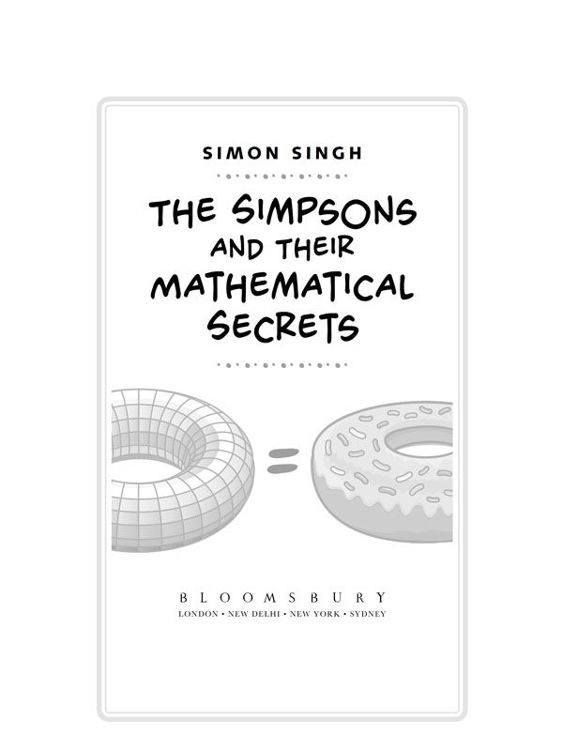

+ =

Contents

T he Simpsons is arguably the most successful television show in history. Inevitably, its global appeal and enduring popularity have prompted academics (who tend to overanalyze everything) to identify the subtext of the series and to ask some profound questions. What are the hidden meanings of Homers utterances about doughnuts and Duff beer? Do the spats between Bart and Lisa symbolize something beyond mere sibling bickering? Are the writers of The Simpsons using the residents of Springfield to explore political or social controversies?

One group of intellectuals authored a text arguing that The Simpsons essentially provides viewers with a weekly philosophy lecture. The Simpsons and Philosophy claims to identify clear links between various episodes and the issues raised by historys great thinkers, including Aristotle, Sartre, and Kant. Chapters include Marges Moral Motivation, The Moral World of the Simpson Family: A Kantian Perspective, and Thus Spake Bart: On Nietzsche and the Virtues of Being Bad.

Alternatively, The Psychology of The Simpsons argues that Springfields most famous family can help us grasp a deeper understanding of the human mind. This collection of essays uses examples from the series to explore issues such as addiction, lobotomies, and evolutionary psychology.

By contrast, Mark I. Pinskys The Gospel According to The Simpsons ignores philosophy and psychology, and focuses on the spiritual significance of The Simpsons. This is surprising, because many characters appear to be unsympathetic toward the tenets of religion. Regular viewers will be aware that Homer consistently resists pressure to attend church each Sunday, as demonstrated in Homer the Heretic (1992): Whats the big deal about going to some building every Sunday? I mean, isnt God everywhere?... And what if weve picked the wrong religion? Every week were just making God madder and madder? Nevertheless, Pinsky argues that the adventures of the Simpsons frequently illustrate the importance of many of the most cherished Christian values. Many vicars and priests agree, and several have based sermons on the moral dilemmas that face the Simpson family.

Even President George H. W. Bush claimed to have exposed the real message behind The Simpsons. He believed that the series was designed to display the worst possible social values. This motivated the most memorable sound bite from his speech at the 1992 Republican National Convention, which was a major part of his reelection campaign: We are going to keep on trying to strengthen the American family to make American families a lot more like the Waltons and a lot less like the Simpsons.

The writers of The Simpsons responded a few days later. The next episode to air was a rerun of Stark Raving Dad (1991), except the opening had been edited to include an additional scene showing the family watching President Bush as he delivers his speech about the Waltons and the Simpsons. Homer is too stunned to speak, but Bart takes on the president: Hey, were just like the Waltons. Were praying for an end to the Depression, too.

However, all these philosophers, psychologists, theologians, and politicians have missed the primary subtext of the worlds favorite TV series. The truth is that many of the writers of The Simpsons are deeply in love with numbers, and their ultimate desire is to drip-feed morsels of mathematics into the subconscious minds of viewers. In other words, for more than two decades we have been tricked into watching an animated introduction to everything from calculus to geometry, from to game theory, and from infinitesimals to infinity.

Homer3, the third segment in the three-part episode Treehouse of Horror VI (1995) demonstrates the level of mathematics that appears in The Simpsons. In one sequence alone, there is a tribute to historys most elegant equation, a joke that only works if you know about Fermats last theorem, and a reference to a $1 million mathematics problem. All of this is embedded within a narrative that explores the complexities of higher-dimensional geometry.

Homer3 was written by David S. Cohen, who has an undergraduate degree in physics and a masters degree in computer science. These are very impressive qualifications, particularly for someone working in the television industry, but many of Cohens colleagues on the writing team of The Simpsons have equally remarkable backgrounds in mathematical subjects. In fact, some have PhDs and have even held senior research positions in academia and industry. We will meet Cohen and his colleagues during the course of the book. In the meantime, here is a list of degrees for five of the nerdiest writers:

J. S TEWART B URNS | BS Mathematics, Harvard University MS Mathematics, UC Berkeley |

D AVID S. C OHEN | BS Physics, Harvard University MS Computer Science, UC Berkeley |

A L J EAN | BS Mathematics, Harvard University |

K EN K EELER | BS Applied Mathematics, Harvard University PhD Applied Mathematics, Harvard University |

J EFF W ESTBROOK | BS Physics, Harvard University PhD Computer Science, Princeton University |

In 1999, some of these writers helped create a sister series titled Futurama, which is set one thousand years in the future. Not surprisingly, this science fiction scenario allowed them to explore mathematical themes in even greater depth, so the latter chapters of this book are dedicated to the mathematics of Futurama. This includes the first piece of genuinely innovative and bespoke mathematics to have been created solely for the purposes of a comedy storyline.

Before reaching those heady heights, I will endeavour to prove that nerds and geeks paved the way for Futurama to become the ultimate TV vehicle for pop culture mathematics, with mentions of theorems, conjectures, and equations peppered throughout the episodes. However, I will not document every exhibit in the Simpsonian Museum of Mathematics, as this would mean including far more than one hundred separate examples. Instead, I will focus on a handful of ideas in each chapter, ranging from some of the greatest breakthroughs in history to some of todays thorniest unsolved problems. In each case, you will see how the writers have used the characters to explore the universe of numbers.

Homer will introduce us to the Scarecrow theorem while wearing Henry Kissingers glasses, Lisa will show us how an analysis of statistics can help steer baseball teams to victory, Professor Frink will explain the mind-bending implications of his Frinkahedron, and the rest of Springfields residents will cover everything from Mersenne primes to the googolplex.

Welcome to The Simpsons and Their Mathematical Secrets.

Be there or be a regular quadrilateral.

I n 1985, the cult cartoonist Matt Groening was invited to a meeting with James L. Brooks, a legendary director, producer, and screenwriter who had been responsible for classic television shows such as