The urge to discover secrets is deeply ingrained in human nature; even the least curious mind is roused by the promise of sharing knowledge withheld from others. Some are fortunate enough to find a job which consists in the solution of mysteries, but most of us are driven to sublimate this urge by the solving of artificial puzzles devised for our entertainment. Detective stories or crossword puzzles cater for the majority; the solution of secret codes may be the pursuit of a few.

For centuries, kings, queens and generals have relied on efficient communication in order to govern their countries and command their armies. At the same time, they have all been aware of the consequences of their messages falling into the wrong hands, revealing precious secrets to rival nations and betraying vital information to opposing forces. It was the threat of enemy interception that motivated the development of codes and ciphers: techniques for disguising a message so that only the intended recipient can read it.

The desire for secrecy has meant that nations have operated codemaking departments, which were responsible for ensuring the security of communications by inventing and implementing the best possible codes. At the same time, enemy codebreakers have attempted to break these codes and steal secrets. Codebreakers are linguistic alchemists, a mystical tribe attempting to conjure sensible words out of meaningless symbols. The history of codes and ciphers is the story of the centuries-old battle between codemakers and codebreakers, an intellectual arms race that has had a dramatic impact on the course of history.

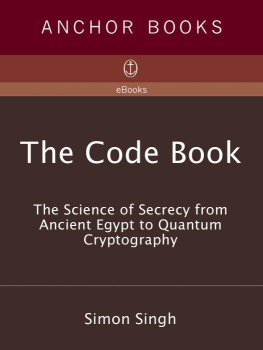

In writing The Cracking Code Book, I have had two main objectives. The first is to chart the evolution of codes. Evolution is a wholly appropriate term, because the development of codes can be viewed as an evolutionary struggle. A code is constantly under attack from codebreakers. When the codebreakers have developed a new weapon that reveals a codes weakness, then the code is no longer useful. It either becomes extinct or it evolves into a new, stronger code. In turn, this new code thrives only until the codebreakers identify its weakness, and so on. This is similar to the situation facing, for example, a strain of infectious bacteria. The bacteria live, thrive and survive until doctors discover an antibiotic that exposes a weakness in the bacteria and kills them. The bacteria are forced to evolve and outwit the antibiotic, and if successful, they will thrive once again and re-establish themselves.

History is punctuated with codes. They have decided the outcomes of battles and led to the deaths of kings and queens. I have therefore been able to call upon stories of political intrigue and tales of life and death to illustrate the key turning points in the evolutionary development of codes. The history of codes is so inordinately rich that I have been forced to leave out many fascinating stories, which in turn means that my account is not definitive. If you would like to find out more about your favourite tale or your favourite codebreaker, then I would refer you to the list of further reading.

Having discussed the evolution of codes and their impact on history, the books second objective is to demonstrate how the subject is more relevant today than ever before. As information becomes an increasingly valuable commodity, and as the communications revolution changes society, so the process of encoding messages, known as encryption, will play an increasing role in everyday life. Nowadays our phone calls bounce off satellites and our emails pass through various computers, and both forms of communication can be intercepted with ease, so jeopardizing our privacy. Similarly, as more and more business is conducted over the Internet, safeguards must be put in place to protect companies and their clients. Encryption is the only way to protect our privacy and guarantee the success of the digital marketplace. The art of secret communication, otherwise known as cryptography, will provide the locks and keys of the Information Age.

However, the publics growing demand for cryptography conflicts with the needs of law enforcement and national security. For decades, the police and the intelligence services have used wiretaps to gather evidence against terrorists and organized crime syndicates, but the recent development of ultrastrong codes threatens to undermine the value of wiretaps. The forces of law and order are lobbying governments to restrict the use of cryptography, while civil libertarians and businesses are arguing for the widespread use of encryption to protect privacy. Who wins the argument depends on which we value more, our privacy or an effective police force. Or is there a compromise?

Before concluding this introduction, I must mention a problem that faces any author who tackles the subject of cryptography: the science of secrecy is largely a secret science. Many of the heroes in this book never gained recognition for their work during their lifetimes because their contribution could not be publicly acknowledged while their invention was still of diplomatic or military value. This culture of secrecy continues today, and organizations such as the U.S. National Security Agency still conduct classified research into cryptography. It is clear that there is a great deal more going on of which neither I nor any other science writer is aware.

Figure 1 Mary Queen of Scots.

1

The Cipher of Mary Queen of Scots

The birth of cryptography,

the substitution cipher and the

invention of codebreaking by

frequency analysis

On the morning of Saturday, October 15, 1586, Queen Mary entered the crowded courtroom at Fotheringhay Castle. Years of imprisonment and the onset of rheumatism had taken their toll, yet she remained dignified, composed and indisputably regal. Assisted by her physician, she made her way past the judges, officials and spectators, and approached the throne that stood halfway along the long, narrow chamber. Mary had assumed that the throne was a gesture of respect towards her, but she was mistaken. The throne symbolized the absent Queen Elizabeth, Marys enemy and prosecutor. Mary was gently guided away from the throne and towards the opposite side of the room, to the defendants seat, a crimson velvet chair.

Mary Queen of Scots was on trial for treason. She had been accused of plotting to assassinate Queen Elizabeth in order to take the English crown for herself. Sir Francis Walsingham, Elizabeths principal secretary, had already arrested the other conspirators, extracted confessions and executed them. Now he planned to prove that Mary was at the heart of the plot, and was therefore equally to blame and equally deserving of death.

Walsingham knew that before he could have Mary executed, he would have to convince Queen Elizabeth of her guilt. Although Elizabeth despised Mary, she had several reasons for being reluctant to see her put to death. Firstly, Mary was a Scottish queen, and many questioned whether an English court had the authority to execute a foreign head of state. Secondly, executing Mary might establish an awkward precedent if the state is allowed to kill one queen, then perhaps rebels might have fewer reservations about killing another, namely Elizabeth. Finally, Elizabeth and Mary were cousins, and their blood tie made Elizabeth all the more squeamish about ordering the execution. In short, Elizabeth would sanction Marys execution only if Walsingham could prove beyond any hint of doubt that she had been part of the assassination plot.