Brains

How They Work and What that Tells Us About Who We Are

Dale Purves

Vice President, Publisher: Tim Moore

Associate Publisher and Director of Marketing: Amy Neidlinger

Acquisitions Editor: Kirk Jensen

Editorial Assistant: Pamela Boland

Operations Manager: Gina Kanouse

Senior Marketing Manager: Julie Phifer

Publicity Manager: Laura Czaja

Assistant Marketing Manager: Megan Colvin

Cover Designer:

Managing Editor: Kristy Hart

Project Editor: Betsy Harris

Copy Editor: Krista Hansing Editorial Services, Inc.

Proofreader: Kathy Ruiz

Senior Indexer: Cheryl Lenser

Compositor: Jake McFarland

Manufacturing Buyer: Dan Uhrig

2010 by Pearson Education, Inc.

Publishing as FT Press Science

Upper Saddle River, New Jersey 07458

FT Press offers excellent discounts on this book when ordered in quantity for bulk purchases

or special sales. For more information, please contact U.S. Corporate and Government Sales,

1-800-382-3419, . For sales outside the U.S., please contact

International Sales at .

Company and product names mentioned herein are the trademarks or registered trademarks

of their respective owners.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form or by any means,

without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing April 2010

ISBN-10: 0-13-705509-9

ISBN-13: 978-0-13-705509-8

Pearson Education LTD.

Pearson Education Australia PTY, Limited

Pearson Education Singapore, Pte. Ltd.

Pearson Education North Asia, Ltd.

Pearson Education Canada, Ltd.

Pearson Educacin de Mexico, S.A. de C.V.

Pearson EducationJapan

Pearson Education Malaysia, Pte. Ltd.

For Shannon, who has always deserved a serious explanation.

Contents

Preface

This book is about the ongoing effort to understand how brains work. Given the way events determine what any scientist does and thinks, an account of this sort must inevitably be personal (and, to a greater or lesser degree, biased). What follows is a narrative about the ideas that have seemed to me especially pertinent to this hard problem over the last 50 years. And although this book is about brains as such, it is also about individuals who, from my perspective, have significantly influenced how neuroscientists think about brains. The ambiguity of the title is intentional.

The idiosyncrasies of my own trajectory notwithstanding, the story reflects what I take to be the experience of many neuroscientists in my generation. Thomas Kuhn, the philosopher of science, famously distinguished the pursuit of what he called normal science from the more substantial course corrections that occur periodically. In normal science, Kuhn argued, scientists proceed by filling in details within a broadly agreed-upon scheme about how some aspect of nature works. At some point, however, the scheme begins to show flaws. When the flaws can no longer be patched over, the interested parties begin to consider other ways of looking at the problem. This seems to me an apt description of what has been happening in brain science over the last couple decades; in Kuhns terms, this might be thought of as a period of grappling with an incipient paradigm shift. Whether this turns out to be so is for future historians of science to decide, but there is not much doubt that those of us interested in the brain and how it works have been struggling with the conventional wisdom of the mid- to late twentieth century. We are looking hard for a better conception of what brains are trying to do and how they do it.

I was lucky enough to have arrived as a student at Harvard Medical School in 1960, when the first department of neurobiology in the United States was beginning to take shape. Although I had no way of knowing then, this contingent of neuroscientists, their mentors, the colleagues they interacted with, and their intellectual progeny provided much of the driving force for the rapid advance of neuroscience over this period and for many of the key ideas about the brain that are now being questioned. My interactions with these people as a neophyte physician convinced me that trying to understand what makes us tick by studying the nervous system was a better intellectual fit than pursuing clinical medicine. Like every other neuroscientist of my era, I set out learning the established facts in neuroscience, getting to know the major figures in the field, and eventually extending an understanding of the nervous system in modest ways within the accepted framework. Of course, all this is essential to getting a job, winning financial support, publishing papers, and attaining some standing in the community. But as time went by, the ideas and theories I was taught about how brains work began to seem less coherent, leading me and others to begin exploring alternatives.

Although I have written the book for a general audience, it is nonetheless a serious treatment of a complex subject, and getting the gist of it entails some work. The justification for making the effort is that what neuroscientists eventually conclude about how brains work will determine how we humans understand ourselves. The questions being askedand the answers that are gradually emergingshould be of interest to anyone inclined to think about our place in the natural order of things.

Dale Purves

Durham, NC

July 2009

1. Neuroscience circa 1960

My story about the effort to make some sense of the human brain begins in 1960, not long after I arrived in Boston to begin my first year at Harvard Medical School. Within a few months, I began learning the foundations of brain science (as it was then understood) from a remarkable group of individuals who had themselves only recently arrived at Harvard and were mostly not much older than me.

The senior member of the contingent was Stephen Kuffler, then in his early 50s and already a central figure in twentieth-century neuroscience. Otto Krayer, the head of the Department of Pharmacology at the medical school, had recruited Kuffler to Harvard from Johns Hopkins only a year earlier. Kufflers mandate was to form a new group in Pharmacology by hiring faculty whose interests spanned the physiology, anatomy, and biochemistry of the nervous system. Until then, Harvard had been teaching neural function as part of physiology, brain structure as a component of traditional anatomy, and brain chemistry as aspects of pharmacology and biochemistry.

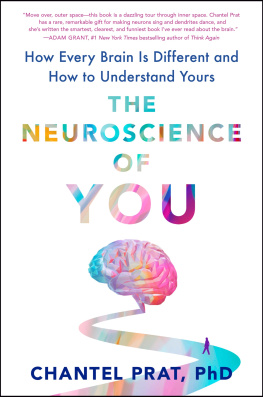

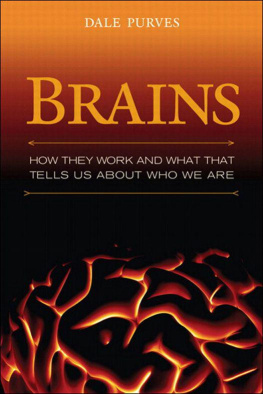

Kuffler had presciently promoted to faculty status two postdoctoral fellows who had been working with him at Hopkins: David Hubel and Torsten Wiesel, then 34 and 36, respectively. Hed also hired David Potter and Ed Furshpan, two even younger neuroscientists who had recently finished fellowships in Bernard Katzs lab at University College London. The last of his initial recruits was Ed Kravitz, who, at 31, had just received his Ph.D. in biochemistry from the University of Michigan. This group () became the Department of Neurobiology in 1966, which soon became a standard departmental category in U.S. medical schools as the field burgeoned both intellectually and as a magnet for research funds. In the neuroscience course medical students took during my first year, Furshpan and Potter taught us how nerve cell signaling worked, Kravitz taught us neurochemistry, and Hubel and Wiesel taught us about the organization of the brain (or, at least, the visual part of it, which was their bailiwick). Kuffler gave a pro forma lecture or two, but this sort of presentation was not his strong suit, and he had the good sense and self-confidence to let these excellent teachers carry the load.

Figure 1.1 The faculty Steve Kuffler recruited when he came to Harvard in 1959. Clockwise from the upper left: Ed Furshpan, Steve Kuffler, David Hubel, Torsten Wiesel, Ed Kravitz, and David Potter. This picture was taken in 1966, about the time the pharmacology group became a department in its own right under Kufflers leadership. (Courtesy of Jack McMahan)