An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Chantel Prat

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

DUTTON and the D colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Illustrations on pages by Andrea Stocco.

Illustration on .

Image on reproduced with permission from Baron-Cohen et al., 2001.

All other images courtesy of the author.

library of congress cataloging-in-publication data

has been applied for.

ISBN 9781524746605 (hardcover)

ISBN 9781524746612 (ebook)

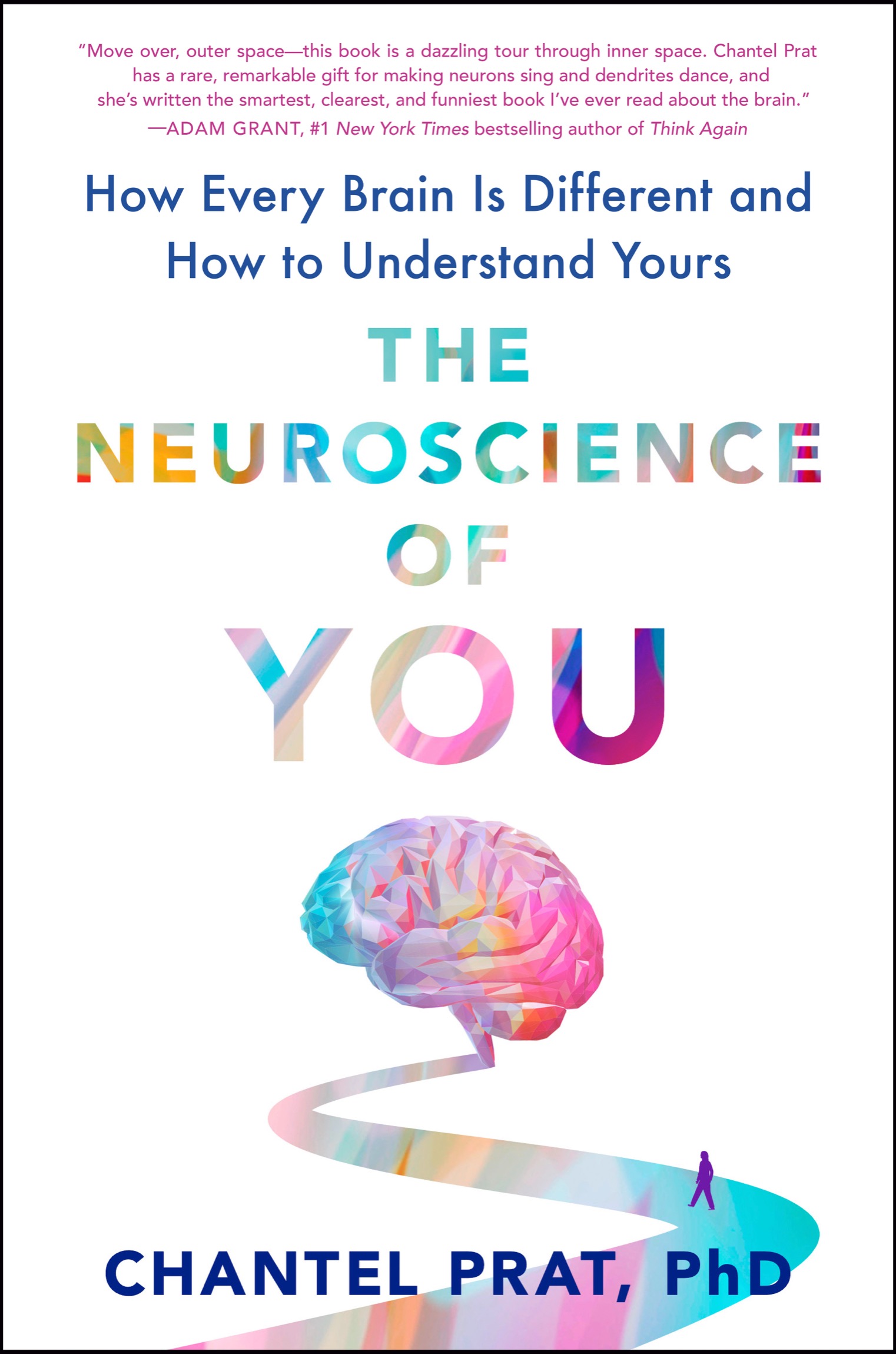

Cover design by Dominique Jones; Jacket image: (brain) Jolygon / Getty Images

Book design by Nancy Resnick, adapted for ebook by Cora Wigen

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors or for changes that occur after publication. Further, the publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

pid_prh_6.0_140597718_c0_r0

To Jasmine, Andrea, and Coccolinafor loving me as I am

CONTENTS

PREFACE

FROM MY BRAIN TO YOURS

They say that everyone has a book in them, but no one ever tells you how hard it is to get that book out of you. Well, they didnt tell me anyway. To be fair, I probably wouldnt have listened. As it turns out, my brain is more of a touch the stove to see how hot kind of learner. To be honest, Im thankful for it. Because even if I get burned now and then along the way, if I had a because they said so type of brain, I wouldnt have done most of the hard things that prepared me to write this book in the first place. And if you learn half as much about your brain when you read it as I did when I wrote it, it will definitely have all been worth it.

Suffice to say that my first book-writing experience has been anything but normal, if there is such a thing. A big part of it involved the experiment we all participated in that began in 2020and Im pretty sure none of us signed a consent form. You know, the one centered on a virus? Id like to think of it as a radical exploration of what psychologists have called the nature-versus-nurture question: How much of what makes you you is inherent in your biological makeup, and how much is a response to your environment? When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, many of us traded the routine parts of our daily lives for pervasive anxiety about our health and the safety of our loved ones.

Fortunately, my day job as a scientist and professor at the University of Washington in Seattle gave me some tools for understanding what might happen to me under these circumstances. But for reasons youll read about in the second half of this book, my knowing better didnt immediately translate into my doing better. Instead, I watched my life transform with equal parts fascination and horror. I was captivated by the differences between how I felt and how the people around me seemed to be coping with the changes in their routines. Some of them got into the best shape of their lives, while I remained stagnant. Others exchanged recipes and became obsessed with baking the perfect loaf of sourdough bread. Not only did I cook less than ever, I didnt do any of the things I always said I would do if I had more time.

Instead, I tried my best to finish Netflix. I cajoled my husband into playing dozens of hours of Pandemic, a board game in which you try to save the world from a virus outbreak. I ate like crap. I drank more than normal. And in the moments of stillness, while gazing at my increasingly protruding navel, I found myself asking the very question that got me into this field in the first place.

Why am I like this?

The answer is pragmatically simple but biologically and philosophically complicated enough to fill a whole shelfful of books.

My brain makes me this way.

I remember the exact moment I first had this realization, and how swiftly it changed my life forever. I was nineteen years old and, after watching one-too-many episodes of Doogie Howser, M.D., was on my way to applying to med school. To meet my last requirement, I signed up for a psychology course at the local junior college that didnt interfere with my day job, selling shoes at Kinneys in the mall. And during our first class, the instructor described the story of Phineas Gage.

Gage was a railway worker who made a mistake in 1848 that caused an iron spike to get blasted through his left cheek and out the top of his head. When it did, it took a decent-size chunk of his brain with it. Surviving such an injury would be remarkable even with todays medical practicesso the fact that Gage got up and literally walked away from the accident is incredible in and of itself. Eventually, many of his physical and mental abilities returned to normal. But the damage Gage sustained to his frontal lobe left his personality fundamentally, and permanently, changed. While Gage was once a well-respected and dependable man, capable of forming and executing rational plans, his physician described him as fitful, irreverent... manifesting but little deference for his fellows, impatient of restraint or advice when it conflicts with his desires, at times pertinaciously obstinate, yet capricious and vacillating, devising many plans of future operations, which are no sooner arranged than they are abandoned in turn for others appearing more feasible. To put it simply, Gage was not the same person after his brain injury.

This fascinated me.

I left class trying to wrap my mind around the fact that the human brain is an organ, just like the heart or the lungs, but that the functioning of this organ makes you you. The lungs oxygenate the blood. The heart circulates the oxygenated blood through the body, and then your brain uses that oxygenated blood to create the energy that gives rise to every thought, feeling, emotion, and action that you identify as your own. Change the brain and you change the person.

What I realized about three months into the pandemic is that on a smaller (and, hopefully, less permanent) scale, my brain was changing. Soaked in cortisola neurochemical related to prolonged stressmy brain was struggling to find a balance between the should do and want to do urges. And I dont know who needs to hear this, but being stressed also majorly kills creativity.

Thankfully, while writing the Mixology chapter, I had the aha moment that gave me some much-needed perspective. Among other things, it reminded me