Richard Dawkins

River Out Of Eden

1995

A Darwinian View of Life

ILLUSTRATIONS BY LALLA WARD

To the memory of

Henry Colyear Dawkins (1921-1992),

Fellow of St. John's College, Oxford:

a master of the art of making things clear.

And a river went out of Eden to water the garden.

Genesis 2:10

Nature, it seems, is the popular name

For milliards and milliards and milliards

Of particles playing their infinite game

Of billiards and billiards and billiards.

Piet Hein

Piet Hein captures the classically pristine world of physics. But when the ricochets of atomic billiards chance to put together an object that has a certain, seemingly innocent property, something momentous happens in the universe. That property is an ability to self-replicate; that is, the object is able to use the surrounding materials to make exact copies of itself, including replicas of such minor flaws in copying as may occasionally arise. What will follow from this singular occurrence, anywhere in the universe, is Darwinian selection and hence the baroque extravaganza that, on this planet, we call life. Never were so many facts explained by so few assumptions. Not only does the Darwinian theory command superabundant power to explain. Its economy in doing so has a sinewy elegance, a poetic beauty that outclasses even the most haunting of the world's origin myths. One of my purposes in writing this book has been to accord due recognition {xii} to the inspirational quality of our modern understanding of Darwinian life. There is more poetry in Mitochondrial Eve than in her mythological namesake.

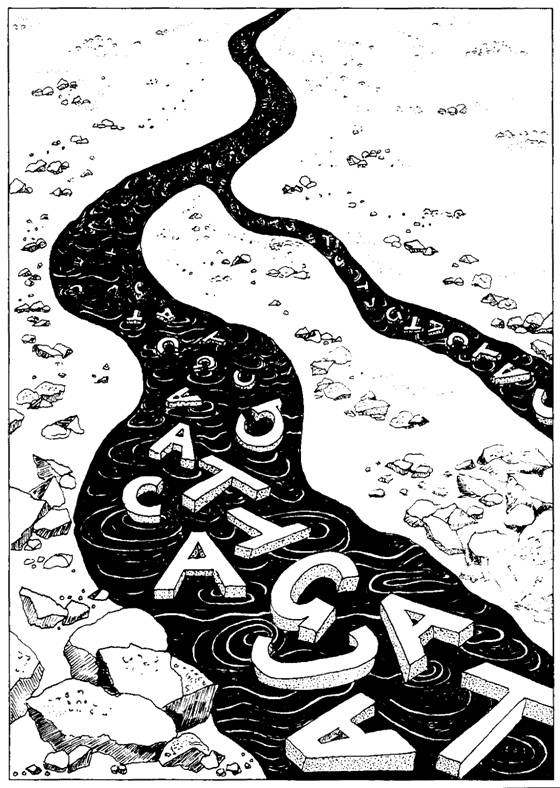

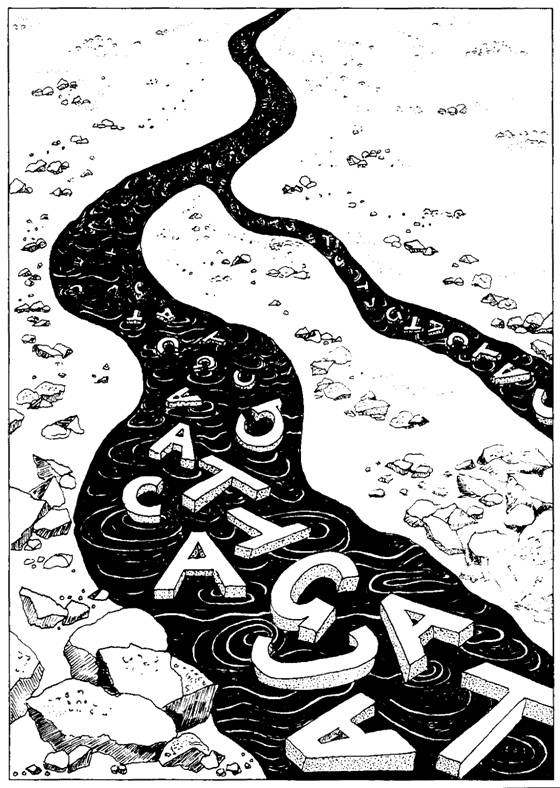

The feature of life that, in David Hume's words, most ravishes into admiration all men who have ever contemplated it is the complex detail with which its mechanisms the mechanisms that Charles Darwin called organs of extreme perfection and complication fulfill an apparent purpose. The other feature of earthly life that impresses us is its luxuriant diversity: as measured by estimates of species numbers, there are some tens of millions of different ways of making a living. Another of my purposes is to convince my readers that ways of making a living is synonymous with ways of passing DNA-coded texts on to the future. My river is a river of DNA, flowing and branching through geological time, and the metaphor of steep banks confining each species' genetic games turns out to be a surprisingly powerful and helpful explanatory device.

In one way or another, all my books have been devoted to expounding and exploring the almost limitless power of the Darwinian principle power unleashed whenever and wherever there is enough time for the consequences of primordial self-replication to unfold. River Out of Eden continues this mission and brings to an extraterrestrial climax the story of the repercussions that can ensue when the phenomenon of replicators is injected into the hitherto humble game of atomic billiards.

During the writing of this book I have enjoyed support, encouragement, advice and constructive criticism in varying combinations from Michael Birkett, John Brockman, Steve Davies, Daniel Dennett, John Krebs, Sara Lippincott, Jerry Lyons, and especially my wife, Lalla Ward, who also did the drawings. Some paragraphs here and there are reworked from articles that have appeared elsewhere. The passages of chapter 1 on digital and analog codes are based on my article in The Spectator of June 11, 1994. Chapter 3's account of Dan Nilsson and Susanne Pelger's work on the evolution of the eye is partly taken from my News and Views article published in Nature on April 21, 1994. I acknowledge the editors of both these journals, who commissioned the articfes concerned. Finally, I am grateful to John Brockman and Anthony Cheetham for the original invitation to join The Science Masters Series.

Oxford, 1994

CHAPTER 1. THE DIGITALRIVER

{1}

All peoples have epic legends about their tribal ancestors, and these legends often formalize themselves into religious cults. People revere and even worship their ancestors as well they might, for it is real ancestors, not supernatural gods, that hold the key to understanding life. Of all organisms born, the majority die before they come of age. Of the minority that survive and breed, an even smaller minority will have a descendant alive a thousand generations hence. This tiny minority of a minority, this progenitorial elite, is all that future generations will be able to call ancestral. Ancestors are rare, descendants are common.

All organisms that have ever lived every animal and plant, all bacteria and all fungi, every creeping thing, and all readers of this book can look back at their ancestors and make the following proud claim: Not a single one of our ancestors died in infancy. They all reached adulthood, and every single one was capable of finding at least one heterosexual partner and of successfully copulating. Not a single one {2} of our ancestors was felled by an enemy, or by a virus, or by a misjudged footstep on a cliff edge, before bringing at least one child into the world. Thousands of our ancestors' contemporaries failed in all these respects, but not a single solitary one of our ancestors failed in any of them. These statements are blindingly obvious, yet from them much follows: much that is curious and unexpected, much that explains and much that astonishes. All these matters will be the subject of this book.

Since all organisms inherit all their genes from their ancestors, rather than from their ancestors' unsuccessful contemporaries, all organisms tend to possess successful genes. They have what it takes to become ancestors and that means to survive and reproduce. This is why organisms tend to inherit genes with a propensity to build a well-designed machine a body that actively works as if it is striving to become an ancestor. That is why birds are so good at flying, fish so good at swimming, monkeys so good at climbing, viruses so good at spreading. That is why we love life and love sex and love children. It is because we all, without a single exception, inherit all our genes from an unbroken line of successful ancestors. The world becomes full of organisms that have what it takes to become ancestors. That, in a sentence, is Darwinism. Of course, Darwin said much more than that, and nowadays there is much more we can say, which is why this book doesn't stop here.

There is a natural, and deeply pernicious, way to misunderstand the previous paragraph. It is tempting to think that when ancestors did successful things, the genes they passed on to their children were, as a result, upgraded relative to the genes they had received from their parents. {3} Something about their success rubbed off on their genes, and that is why their descendants are so good at flying, swimming, courting. Wrong, utterly wrong! Genes do not improve in the using, they are just passed on, unchanged except for very rare random errors. It is not success that makes good genes. It is good genes that make success, and nothing an individual does during its lifetime has any effect whatever upon its genes. Those individuals born with good genes are the most likely to grow up to become successful ancestors; therefore good genes are more likely than bad to get passed on to the future. Each generation is a filter, a sieve: good genes tend to fall through the sieve into the next generation; bad genes tend to end up in bodies that die young or without reproducing. Bad genes may pass through the sieve for a generation or two, perhaps because they have the luck to share a body with good genes. But you need more than luck to navigate successfully through a thousand sieves in succession, one sieve under the other. After a thousand successive generations, the genes that have made it through are likely to be the good ones.

Next page