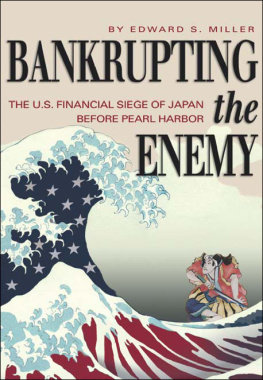

Bankrupting the Enemy

BANKRUPTINGtheENEMY

The U.S. Financial Siege of Japan

before Pearl Harbor

EDWARD S. MILLER

NAVAL INSTITUTE PRESS

Annapolis, Maryland

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2007 by Edward S. Miller

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Miller, Edward S.

Bankrupting the enemy : the U.S. financial siege of Japan before Pearl Harbor / Edward S. Miller.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61251-118-4

1. Economic sanctions, AmericanJapanHistory20th century. 2. United StatesForeign economic relationsJapan. 3. JapanForeign economic relationsUnited States. 4. JapanEconomic conditions1918-1945. I. Title.

HF1602.15.U6M55 2007

940.53'113dc22

2007016455

14 13 12 11 10 09 08 079 8 7 6 5 4 3 2

First printing

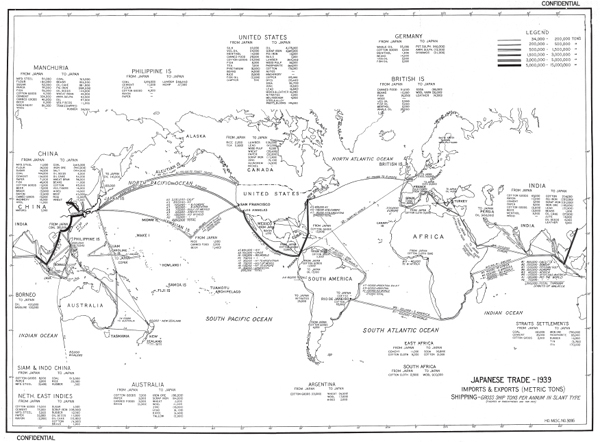

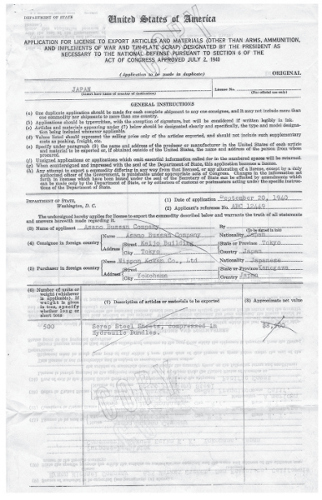

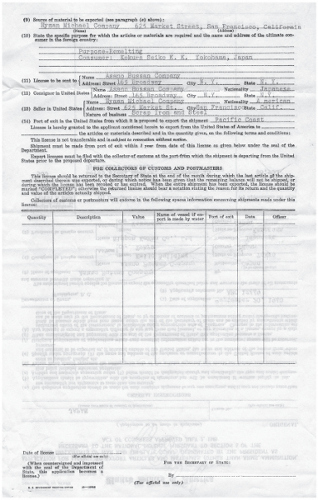

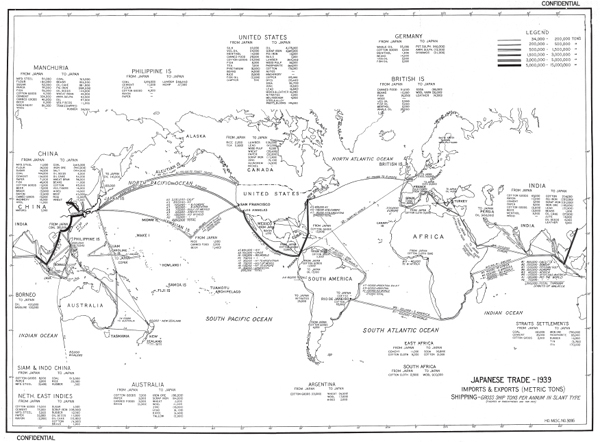

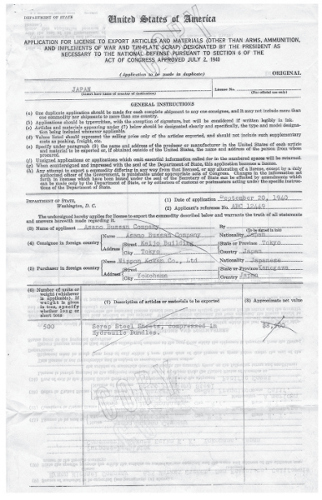

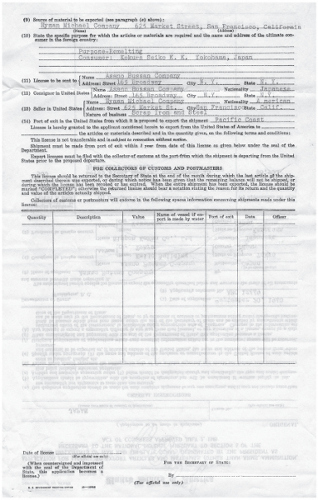

Front endleaf: Japans Foreign Trade, 1939. File 502-300, Japan Exports, Office of Naval Intelligence, Monograph Files, Japan 193946, Box 48, RG 38, NA. Back endleaf: Application for Export License, front and back. Office of Alien Property Custodian, 6th File, MLR Entry 216, Box 122, Yokohama Specie Bank General Banking Records, 19201941, RG131, NA.

CONTENTS

Photographs follow

Figures

Endsheets

Japans Foreign Trade, 1939

Application for Export License

Charts

Tables

T he American perception of Japans economic and financial vulnerability dated back to a time thirty-five years before Pearl Harbor. President Theodore Roosevelt grew concerned after the victory over Russia in 1905 that Japan would seek to dominate China in contravention of the U.S. Open Door policy, which championed independence and free trade for China. Japan would perceive that policy, and U.S. bases in the Philippines and Hawaii, as barriers to building an empire. Roosevelt asked the U.S. Navy for a plan to fight Japan, if and when necessary.

The result, War Plan Orange, was fundamentally an economic strategy in both origins and outcome. (Japan was code-named Orange, the United States Blue.) The godfathers of the plan, Admirals George Dewey and Alfred Thayer Mahan, had served as young officers enforcing the Unions Anaconda Plan against the Confederacy, an island vulnerable to economic blockade. They and later disciples in the War Plans Division of the Navy demonstrated a fierce mindset favoring vigorous action, a mindset echoed by civilian bureaucrats who advocated a nonviolent economic and financial war against Japan in the crisis years before Pearl Harbor.

While U.S. military planners assumed Japans war aims would be limiteda surprise attack, victory in naval battle, and a negotiated peace ceding dominance of East Asiatheir aim was a crushing defeat of the enemy, an aim demanded by an aroused public. They understood that Japan, an island nation poor in natural resources, depended on overseas trade for the sinews of war and its very economic life. The Japanese Empire produced food enough, but industrialization and conquests led to voracious needs of metals and fuels. The planners designed a strategy of siege. After initial losses, Blue forces would

In the 1930s peaceable internationalist governments in Tokyo gave way to military-dominated regimes. The anticipated violations of the Open Door unfolded in the invasion of China and designs against colonies of the Western powers. The helplessness of Japan, if isolated economically and financially, evolved into an axiom at a time when the U.S. government was averse to fighting a war. When national policy to deter Japanese aggression took root, the United States gradually deployed its vast economic and financial powers to strangle Japan by means other than ships and bombs. It was a Plan Orange strategy in peacetime.

The story now turns to the U.S. strategy of achieving the nations foreign policy aims, without combat, by bankrupting Japan.

T he focus of this book is the United States financial and economic sanctions against Japan before Pearl Harbor, reconstructed primarily from official U.S. sources. Many histories have been written about the run-up to the Pacific war, largely by diplomatic historians, understandably in view of the centrality of the Department of State in U.S.-Japanese negotiations and that departments voluminous, well-organized files, which were declassified long ago, some as early as 1943, supplemented by forty volumes of congressional hearings of 1946 about Pearl Harbor and precursor events.

Financial and economic records, however, were far less accessible until fifty years after World War II. Not until 1996 did the National Archives, at the prompting of a U.S. interagency group on Nazi assets, declassify and make more readily available the worldwide papers of the Treasury Departments Office of the Assistant Secretary of International Affairs, established on 25 March 1938 and directed by Harry Dexter White..

The main Japanese sources are the excellent historical data published in bilingual tables by the Japan Statistical Association, and Japanese commercial and diplomatic studies published in English. Most of Japans official records of 1931 to 1945 were burned in the two-week interval between the surrender and the occupation in 1945 in anticipation of war crimes trials. However, economic information for the last prewar decade was reconstructed in detail and published by the U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey and by investigators of the Supreme Commander of the Allied Powers during the postwar occupation.

Japanese financial and trade statistics are usually presented for fiscal years beginning 1 April, so that, for example, 1940 means the twelve months beginning 1 April 1940 and ending 31 March 1941. U.S. statistics are usually given for calendar years, making some comparisons awkward. Physical trade units are stated here in U.S. measures such as ounces, tons, or yards, or occasionally in metric measures. Some Japanese figures have been converted from metric units or the ancient weights and measures then used in trade.

Money figures are stated in U.S. dollars, the dominant world currency then and now. The 193541 dollar was worth about $10 in 2007 dollars if measured by an average of U.S. prices of goods, or about $25 if measured by average U.S. wages. In exchange markets the yen was worth 49 to 50 cents from 1899 until devalued on 14 December 1931. It dipped as low as 20 cents in 193233, then stabilized at 28.3 cents until 24 October 1939, when it was devalued to 23.4 cents. There was no organized exchange market after 25 July 1941; fragmentary trading in China suggests that in late 1941 the yens gray market value was much lower, perhaps 11 or 12 cents. After a devastating wartime and postwar inflation, the yen was stabilized at 0.28 cents (360 per dollar). It subsequently has risen to almost 1 cent (100 per dollar).

The U.S. economy is roughly 150 times larger than in 193540 in unadjusted dollars and about 10 times larger adjusted for price inflation. The Japanese economy is about 500 times larger in unadjusted U.S. dollars and about 50 times larger adjusted for U.S. inflation. The prewar Japanese economy was about 8 percent the size of the American. In 2006 it was about 40 percent as large. Japanese foreign trade is now about seven hundred times greater in nominal value, $1.1

Next page