Copyright 2013 by Jason Fagone

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Crown Publishers,

an imprint of the Crown Publishing Group,

a division of Random House LLC,

a Penguin Random House Company, New York.

www.crownpublishing.com

CROWN and the Crown colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Fagone, Jason.

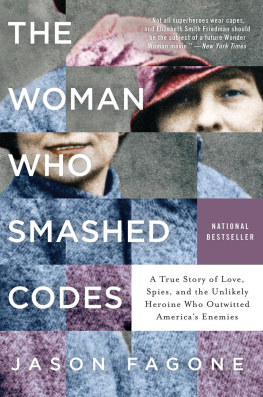

Ingenious : a true story of invention, automotive daring, and the race to revive America / Jason Fagone.

pages cm

1. AutomobilesEnergy consumptionResearchUnited States. 2. AutomobilesEnergy consumptionTechnological innovationsUnited States. 3. AutomobilesDesign and constructionCompetitionsUnited States. 4. InventorsUnited States. 5. Creative abilityUnited States. 6. Industrial development projectsUnited States. I. Title. TL151.6F34 2013

629.222dc23 2013023442

ISBN 978-0-307-59148-7

eISBN: 978-0-307-59150-0

Images on the proceeding pages are courtesy of the following contributors: courtesy of Edison2.

Jacket design by Keenan

Jacket illustration courtesy of Edison2

v3.1

for Dana and Mia

contents

introduction

A Nation of Inventors

A few years ago, in the post-bailout gloom of the Great Recession, I saw a story in the news that stuck. A foundation in California was offering a large cash bounty to anyone who could make a safe, practical, 100-mile-per-gallon car. Gas prices were going up, oil reserves were going down, the planet was baking; something had to be done. The foundation had raised $10 million, and now it was dangling the money from a string. Hit the target, win a piece of the jackpot. The Automotive X Prize it was called. Big companies could enter, but so could lone inventors and garage hackers and start-ups. Size didnt matter, only the quality of the machine.

Im not a car person. When I was a kid, I used to read Car and Driver and Motor Trend with my father, a longtime chemist at DuPont. He was the kind of guy who secretly coveted a sports car but always went for the responsible family sedan instead. I liked to clip out pictures of futuristic concept cars, high-mileage pods made of exotic materials, and tape them to the wall of my room. But it was just a phase. Whatever I learned from reading the magazines Ive long forgotten. I drive a 2002 Honda Accord and have the oil changed at the dealer, and when I get behind the wheel, I dont want to think about whats happening under the hood. Im thirty-five with a wife and a young daughter and a small stack of Raffi CDs in the front. I just want the thing to work.

Still, the idea of the Prize resonated with me. The psychology of itusing a bald appeal to human greed to achieve an idealistic goalmade a lot of sense. If you want to get a job done, you pay for it, right? And the foundations interest in small inventors seemed more than justified by the recent economic catastrophe. The big guys had failed us in America. Wall Street, General Motorsour rich elites had blown up the economy, and now they were sucking down billions in taxpayer bailouts. I read that Henry Fords Model T got 20 miles to the gallon. That was in 1908. A century later, the average new car in America got 21 miles per gallon. It was hardly crazy to think that a tiny, nimble company, or even a tinkerer in a garage, could design a more efficient car than GM. It seemed important, actually, to go looking.

Soon I was poring over every article on the X Prize I could find, and the more I learned, the more legitimate it appeared. The sponsor was the solid, reputable Progressive Insurance Company. The CEO of the foundation was a physician and successful entrepreneur. He insisted the cars had to be real. They could run on electricity, hydrogen, gasoline, ethanol, steam, or some amazing new fuel as yet unknown, but, according to the rules of the X Prize, they had to be production-capable and designed to reach the marketno concept cars, no science projects that would disappear beneath tarps after the contest was over. They had to seat at least two large people comfortably, a large person being defined as an adult male in the 95th percentile of height and weight: six feet two inches tall, 215 pounds. Thats just the slightest bit smaller than the average NFL quarterback. Also, a driver knowing nothing about a particular car had to be able to figure out how to drive it within ten minutes. Grandma had to be able to drive it.

In early 2010, I reached out to several teams. One was a group of garage hackers in an Illinois cornfield. A second was a team of sports-car racers from Lynchburg, Virginia. A third was a group of students and teachers at an inner-city high school. A fourth was a start-up company in Southern California. For the most part, theyd all been working on their cars since the Prize was first announced, in 2007, and now they were ready to test them, in a series of increasingly rigorous competition stages throughout the spring and summer at a NASCAR track in rural Michigan.

I started traveling around the country, meeting racers, robot-builders, and a guy who designed stealth bombers and called himself Aero Man, and it wasnt long before Id dropped most of my other freelance journalism work to focus on the Prize. Watching the teams prepare their cars for the track, I felt more hopeful than Id felt in years: In the thick of the worst economic funk since the Great Depression, here were all these people working furiously in garages and warehouses and barns, trying to hit a series of staggeringly difficult targets that no government, automaker, or inventor had ever achieved.

In April, June, and July, I followed the teams to Michigan, where they battled each other with millions on the line. Then, after the competition phase of the Prize was over, I continued to visit them for the next three years, well into 2013. Partly it was simple curiosity. I knew their story wouldnt end with the Prize; it wouldnt end until the market either accepted or rejected their ideas. I wanted to write a real history of their effort. I wanted to know what would happen next. Would the automakers court them or ignore them? Could a handful of inventors shape a powerful industry?

But there was another reason I kept following the teams: By now, I was convinced that their story spoke to something larger than the future of cars.

Over the last half century, as the American economy has shifted toward knowledge workas the factories that used to sustain cities like Detroit and Baltimore and Philadelphia have died, leaving vast swaths of poor and minority kids without access to jobs; as Wall Street has siphoned off a generation of young overachievers and put them to work writing algorithms to extract billions from markets; and as other strivers have moved to Silicon Valley to find their fortune by creating the next new viral whateverinventing things that matter in America has increasingly become the province of elites. And it didnt used to be this way. We are called the nation of inventors, Mark Twain said in 1890, and we are. We could still claim that title and wear its loftiest honors if we had stopped with the first thing we ever invented, which was human liberty. In Leaves of Grass, Walt Whitman wrote, A new worship I sing / You captains, voyagers, explorers, yours / You engineers, you architects, machinists, yours. What excited these guys about invention was the democracy of it. Invention as an everyday pursuit, a way of using the materials at hand to get along in a raw place and explore new terrain. An impulse to scrounge and tinker that would later find its greatest flowering on the Michigan farm of Henry Ford, the Ohio bicycle shop of the Wright Brothers, and the California garage of Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak, who were all anonymous nobodies when they began the work that changed the world.