Also by Derek Lundy

Scott Turow: Meeting the Enemy Barristers and Solicitors in Practice (General Editor)

Godforsaken Sea

RACING THE WORLDS

MOST DANGEROUS

WATERS

by Derek Lundy

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

Published by

ALGONQUIN BOOKS OF CHAPEL HILL

Post Office Box 2225

Chapel Hill, North Carolina 27515-2225

a division of

WORKMAN PUBLISHING

225 Varick Street

New York, New York 10014

1998 by Derek Lundy.

First published in a somewhat different form by Alfred A. Knopf Canada. Algonquin edition published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Random House of Canada Limited, 1999 by Derek Lundy. All rights reserved.

For permission to use excerpts from copyrighted works, grateful acknowledgment is made to the copyright holders, publishers, or representatives named on pages 72, which constitutes an extension of the copyright page.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for a previous edition of this work.

E-book ISBN 978-1-61620-247-7

To Alexander Dickson Lundy (19211995)

Once a sailor

There is a poetry of sailing as old as the world.

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPRY

Contents

Authors Note

All references to miles are nautical miles. A nautical mile equals 1.15 statute miles or 1.85 kilometers. Speeds and wind velocities are stated in knots, or nautical miles per hour (mph). So, for example, 25 knots is 29 mph or 46 kilometers per hour (kph); 50 knots is almost 58 mph or 93 kph. A wind officially becomes hurricane force when it blows at or above 64 knots73 mph or 118 kph.

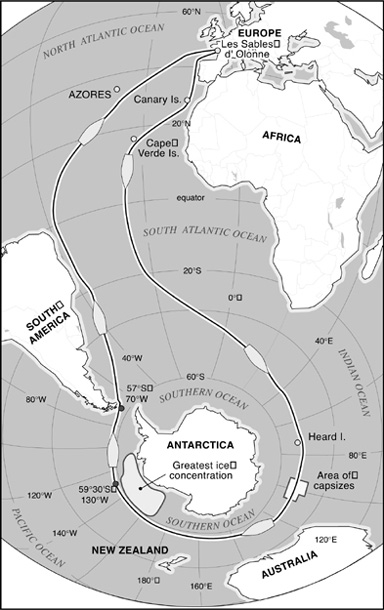

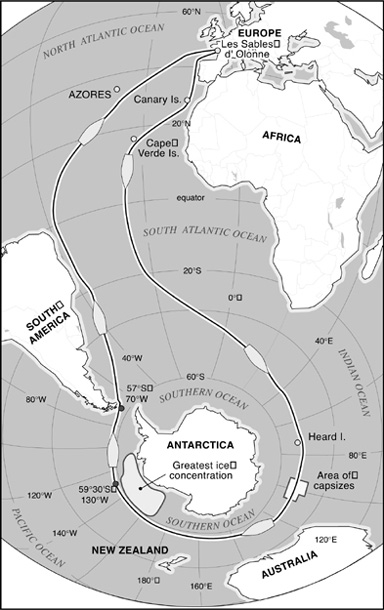

The Vende Globe, 199697

Philippe Jeantot, race organizer and director

The Sailors

Christophe Auguin, Godis

Isabelle Autissier, PRB

Tony Bullimore, Exide Challenger

Catherine Chabaud, Whirlpool Europe 2

Bertrand de Broc, Votre nom autour du mondePommes Rhne Alpes

Patrick de Radigus, Afibel

Raphal Dinelli, Algimouss

Thierry Dubois, Pour Amnesty International

Eric Dumont, Caf Legal le Got

Nandor Fa, Budapest

Pete Goss, Aqua Quorum

Herv Laurent, Groupe LG Traitmat

Didier Munduteguy, Club 60e Sud

Yves Parlier, Aquitaine Innovations

Gerry Roufs, Groupe LG2

Marc Thiercelin, Crdit Immobilier de France

PROLOGUE

Signatures of all things I am here to read, seaspawn and seawrack...

JAMES JOYCE, Ulysses

Each time I looked astern, I jumped. The dark shape on the stern rail seemed humana squat little man crouching there malevolently, ready to leap at me. I looked back every ten seconds or so to try to gauge the height and speed of the following waves. Working the tiller with both hands, I tried to keep the boat square to the wind and seas. To maintain my bearings in the dark, I had to feel the wind on my face, try to catch the phosphorescent flash of the breaking crests. Every time I looked, the man-shape startled me. During each short interval, I forgot he was there. For half an hour, Id been looking back, jumping, forgetting, looking back, jumping.... On the horizon, five hundred miles from land, I imagined I glimpsed the skyline of a great city of lights.

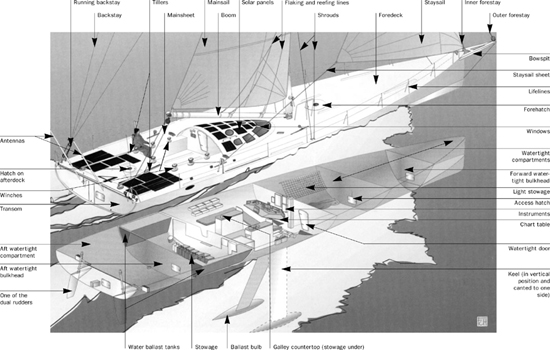

The boat was driving hard to the southeast under a double-reefed staysailabout thirty square feet of drum-tight sail just forward of the mast. The wind was pushing us at almost six knots, as fast as our little boat could go. The resistance the bow wave created as the boat moved through the sea, and the friction between the hull and the water, set a speed limit that, theoretically, we couldnt exceed. But sometimes we accelerated right through the immutable laws of hydrodynamics as the boat surfed down the face of a twelve-foot Atlantic wave.

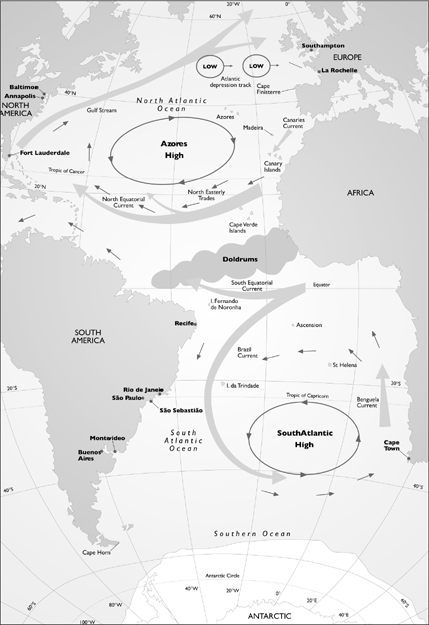

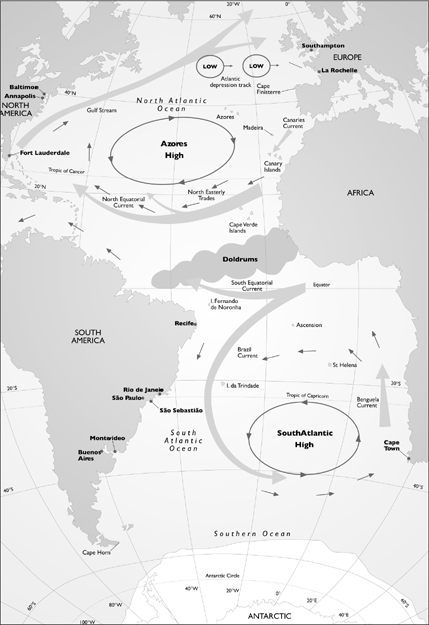

We were out on the open ocean for the first time in our livesmy wife and Ion a thirty-one-foot sailboat weighing five and a half tons. Id sailed small boats for most of my life, but rarely out of sight of land. This passage was differentno Great Lakes slog to another marina or coastal hop to the next homey anchorage. Wed crossed the Gulf Stream, and now we were aiming for the heart of the Bermuda Triangle, across the Sargasso Sea, southeast as hard as we could go, away from the dangerous December storm latitudes. We would keep this heading until we hit sixty-five degrees west longitudenicknamed I65, like an interstate highway, because of the flow of southbound boat traffic to the Caribbean. Then we would turn due south, looking for the steady northeast trade winds to ride into Charlotte Amalie or Jost van Dyke.

Leaving Charleston Bay, we had sailed on a gentle southwest breeze for several hours. Just before sunset, the land a dark line astern, we saw dolphins about fifty yards off our port side. They streaked toward us in a leaping, joyful bunch. They did what dolphins dochittered, dove, jumped, surfed our bow wave. Then, bored with our three knots, they sped off to bluer pastures. We were thrilled with the exuberance and insouciance of the wild dolphins, their sheer at-homeness in the ocean. They soothed our fear of the thirteen hundred miles ahead. With such animals in it, the sea seemed friendly, benign, comprehensible. Everything would be all right after all.

Four days later, things were not all right. The sea, among its many qualities, is an unerring discoverer of weakness, and it had discovered one of ours. I hadnt properly sealed the engine ignition and gauges, which were set into one of the locker sides in the cockpit at about shin height. That night, on watch, I suddenly realized that the intermittent chugging noise Id been hearing over the sounds of wind and sea was our auxiliary diesel engine trying to start itself. Seawater, scooped up by the bows plunge, swept down the windward side-deck and into the cockpit, where it swirled out the drains in a luminous kaleidoscope. Some of the water had got into the ignition switch and shorted it out, creating the same effect as turning the ignition key. The engine, trying to start against the iron grip of the transmissionit was in gear to stop the propeller from freewheeling as we sailedsoon wore down the batteries. I heard what was happening just as they were going dead flat. We used the engine to get in and out of ports and anchorages, to escape local calms, and to charge our batteries for electricity. It could also come in handy sometimes in bad weather at sea, to help control the boat. But otherwise, when we were on a passage, the engine was a passive bystander.

We had spares or tools to replace or fix just about everything on board. But our ethos of self-sufficiency and redundancy was tailored for matter, not energy. Now we needed the two things we didnt have two of. To recharge the batteries, we needed the engine. The engine, which we could theoretically start with a hand crank in the absence of electricity, now refused to start that way. If we couldnt start the engine, we couldnt charge the batteries. Without the batteries, we had no electricity and couldnt start the engine. No electricity meant no electric lights below (although we had kerosene spares), no log (to tell us speed and distance sailed), no compass light. No engine meant that we were truly a sailing vessel. We would have to wait for wind in the inevitable calms of the horse latitudes. The spare diesel fuel wed carried to get us through them was now useless ballast.

Next page