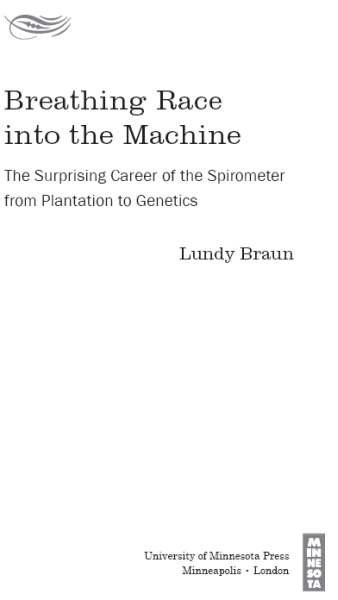

The publication of this book was assisted by a bequest from Josiah H. Chase to honor his parents, Ellen Rankin Chase and Josiah Hook Chase, Minnesota territorial pioneers.

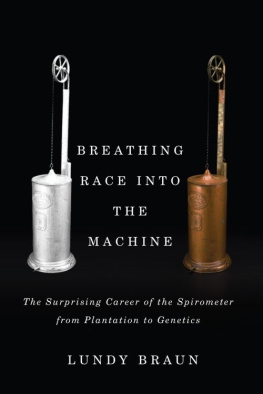

Portions of were previously published as Spirometry, Measurement, and Race in the Nineteenth Century, Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 60 (2005): 13569.

Copyright 2014 by the Regents of the University of Minnesota

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

E-ISBN 978-1-4529-4100-4

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

To my sister Martha

19511979

Contents

Working-Class Bodies in Victorian England

The Science of White Supremacy in the Nineteenth-Century United States

Making and Measuring Whiteness

Vitality in Turn-of-the-Century Britain

The Racial Factor in Scientific Medicine

Physiological Testing in South African Gold Mines

This book represents the culmination of my journey from the laboratory to the archive that began in the late 1990s after I read an article in my local newspaper about race correction of pulmonary function in an asbestos class-action lawsuit. Having just joined the Race in Science and Medicine Workshop at MIT, organized by Evelynn Hammonds, I was intrigued by the idea of correcting for race. A conversation with my good friend David Kern, a wonderfully thoughtful physician in occupational medicine, revealed that race correction was standard practice in pulmonary medicine. In his usual meticulous fashion David assembled key articles on the topic for me to read. What I initially conceptualized as a short article became a long but truly enjoyable excursion in the history of race and lung-function testing.

The encouragement of friends and colleagues on three continents made the process of researching and writing this book a pleasure. I offer the usual caveat that I alone am responsible for the interpretation of this history. My sincere appreciation goes to colleagues at Brown University. I have been fortunate that the structure at Brown allowed me to cross disciplinary (and epistemological) boundaries that are usually difficult to navigate. In the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, I thank Agnes Kane, my chair; Kim Boekelheide; and my former chair, Nelson Fausto (who, sadly, did not live to read this book), for unflagging support and encouragement over the years when it would have been much easier on the department if I did my job in a more conventional way. Special thanks go to my colleagues in Africana studies, especially Lewis Gordon, who in 2001 invited me to join the Department of Africana Studies, and subsequent chairs Tony Bogues, Tricia Rose, and Corey Walker, who provided important intellectual support for this work. Anne Fausto-Sterling organized the Science and Technology Studies program just as I was making the shift from basic science to historical research. Her intellectual generosity and that of other faculty members in STS were critical to the evolution of this study.

I am deeply grateful to those who took time out of their busy schedules to read drafts of one or more chapters: Rina Bliss, Molly Braun, Merlin Chowkwanyun, Anne Fausto-Sterling, Franoise Hamlin, Agnes Kane, David Kern, Sophie Kisting, Nancy Jacobs, Miriam Reumann, Susan Reverby, Joan Richards, Samuel Roberts, David Rosner, and Amy Slaton. Their comments enriched the manuscriptand made the process more interactive and fun. In addition to her famously quick turnarounds on copy, Susan deserves special mention for support and advice as the project evolved. That this project became a book is largely due to Keith Wailoo, who first suggested at a conference in 2006 that I consider the idea. Miriam, Merlin, David, and Molly were truly heroic in reading and commenting on the entire manuscript. I thank Peter Braun for his legal insight on the asbestos case.

Friends and colleagues in South Africa played a critical role in the development of this project. In particular, Neville Alexander, Eugene Caincross, Sophie Kisting, and Karen Press were gracious in helping me appreciate South Africas complex history and the brutal legacy of a racialized mining system. Nevilles vision of and sacrifices for a more just future hover over this book; I am deeply saddened by his death. Sophie stands out for her remarkable insight. She took an immediate interest in the project and helped to arrange interviews with South Africans involved in the debate over reference standards and several seminars at an early stage of this project. The work of Jonny Myers was a constant inspiration. Tony Davies was remarkably generous with his time answering e-mails and helping me locate valuable documents from the Pneumoconiosis Research Unit.

I conducted a large number of interviews with physicians and activists in the United States, South Africa, and Britain. Although they will remain anonymous under the terms of my human subjects approval, I am grateful for their time and interest in discussing this complicated topic. I gained valuable insights over the years from many participants, especially the organizer, Evelynn Hammonds, in the Race in Science and Medicine Workshop, first held at MIT and then Harvard; the Race Seminar in Cape Town; the RACEGEN listserv; and numerous seminars and talks. I thank Kay Dickersin and Melanie Wolfgang for their patient collaboration on the incredibly grueling systematic review, which informs sections of this book.

I was fortunate to be the recipient of several grants that gave me precious time and funding to work on this project: a professional development grant from the National Science Foundation, a National Science Foundation Scholar Award, a Royce Teaching Fellowship, and a Salomon grant from Brown University.

Librarians in South Africa, the United States, and South Wales were extraordinarily gracious with their time and knowledge. Special mention goes to the staff at Amherst College, Brown Universitys John Hay Library, the National Library of South Africa, and to Sian Williams of the fabulous South Wales Coal Miners Library. Diana Wall from Museum Africa and Rosemary Soper of the Archie Cochrane Archives went way beyond the call of duty in searching their collections for suitable images.

Thank you to Jason Weidemann and members of the editorial, production, and marketing staff at the University of Minnesota Press. The expert copyediting of Roxanne Willis, David Thorstad, and Nancy Sauro made this a more readable book. I thank David Luljak for his meticulous indexing and Beth Mellor for the maps.

I deeply appreciate the sage comments, advice, and encouragement I received from the two reviewers of this book, Troy Duster and Steven Epstein.

Finally, I express my love and gratitude to Lucia, Catherine, and John Trimbur for their patience with what became my strange and lengthy obsession with something as esoteric as lung function. They each read and edited drafts of chaptersJohn more drafts than he cares to recall. John quietly endured my sense of a vacation to mines in South Africa, South Wales, the United States, and Canada. (Sorry, I dont anticipate this will change.)

Precision carries immense weight in the twentieth century... It connotes trustworthiness and elegance in the actions or products of humans and machines. Precision is everything that ambiguity, uncertainty, messiness, and unreliability are not. It is responsible, nonemotional, objective, and scientific. It shows quality... These values of precision have become part of our heritage.