For Nat

Mathematics is a joke.

Im not being funny.

You need to get a joke just like you need to get maths.

The mental process is the same.

Think about it. Jokes are stories with a set-up and a punch line. You follow them carefully until the payoff, which makes you smile.

A piece of maths is also a story with a set-up and a punch line. Its a different type of story, of course, in which the protagonists are numbers, shapes, symbols and patterns. Wed usually call a mathematical story a proof, and the punch line a theorem.

You follow the proof until you reach the payoff. Whoosh! You get it! Neurons go wild! A rush of intellectual satisfaction justifies the initial confusion, and you smile.

The ha-ha! in the case of a joke and the aha! in the case of maths describe the same experience, and this is one of the reasons why understanding mathematics can be so enjoyable and addictive.

Like the funniest punch lines, the finest theorems reveal something you are not expecting. They present a new idea, a new perspective. With jokes, you laugh. With maths, you gasp in awe. It was precisely this element of surprise that made me fall in love with maths as a child. No other subject so consistently challenged my preconceptions.

The aim of this book is to surprise you, too. In it, I embark on a tour of my favourite mathematical concepts, and explore their presence in our lives. I want you to appreciate the beauty, utility and playfulness of logical thought.

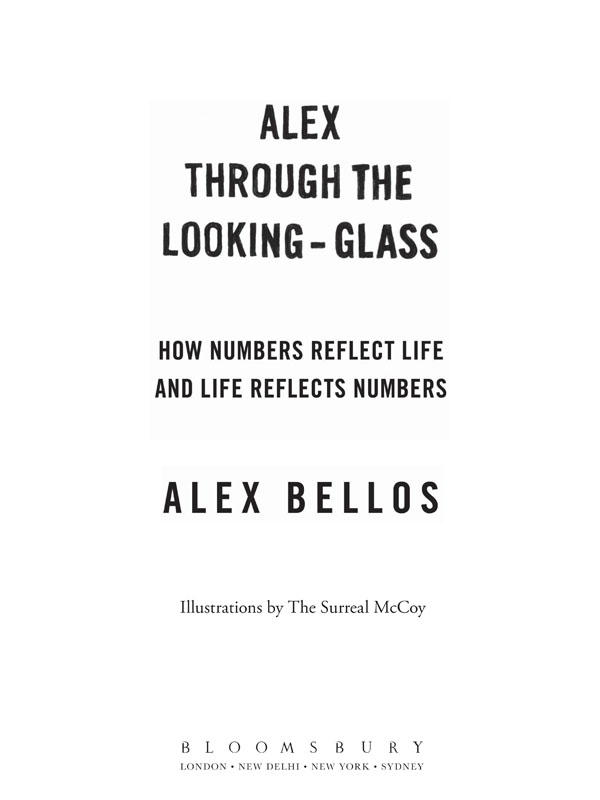

My previous book, Alexs Adventures in Numberland, was a journey into mathematical abstraction. This time I come down to earth: my concern is as much the real world, reflected in the mirror of maths, as it is the abstract one, inspired by our physical experiences.

Firstly, I put humans on the couch. What are the feelings we have for numbers, and what triggers these feelings? Then I put numbers on the couch, individually and as a group. Each number has its own issues. When we engage with them en masse, however, we see fascinating behaviour: they conduct themselves like a well-organized crowd.

We depend on numbers to make sense of the world, and have done so ever since we started to count. In fact, perhaps the most surprising feature of mathematics is how extraordinarily successful it has been, and continues to be, in enabling us to understand our surroundings. Civilization has progressed as far as it has thanks to discoveries about simple shapes like circles and triangles, expressed pictorially at first, and later in the vernacular of equations.

Maths, I would argue, is the most impressive and longest-running collective enterprise in human history. In the following pages I follow the torch of discovery from the Pyramids to Mount Everest, from Prague to Guangzhou, and from the Victorian drawing room to a digital universe of self-replicating creatures. We will meet swashbuckling intellects, including familiar names from antiquity and less familiar names from the present day. Our cast includes a cravat-wearing celebrity in India, a gun-toting private investigator in the United States, a member of a secret society in France, and a spaceship engineer who lives near my London flat.

As we roam across physical and abstract worlds, we will probe well-known concepts, like pi and negative numbers, and encounter more enigmatic ones, which will become our confidantes. We will marvel at concrete applications of mathematical ideas, including some that actually are made of concrete.

You dont need to be a maths whizz to read this book. Its aimed at the general reader. Each chapter introduces a new mathematical concept, and assumes no previous knowledge. Inevitably, however, some concepts are more stretching than others. The level sometimes reaches that of an undergraduate degree, and, depending on your mathematical proficiency, there may be moments of bewilderment. In these cases, skip to the beginning of the next chapter, where I reset the level to elementary. The material might make you feel a bit dizzy at first, especially if it is new to you, but thats the point. I want you to see life differently. Sometimes the aha! takes time.

If all this sounds a bit serious, it isnt. The emphasis on surprise has made maths the most playful of all intellectual disciplines. Numbers have always been toys, as much as they have been tools.

Not only does maths help you understand the world better, it helps you enjoy it more, too.

Alex Bellos

January 2014

Jerry Newport asked me to pick a four-digit number.

2761, I said.

Thats 11 251, he replied, reciting the numbers in one continuous, unhesitant flow.

2762. Thats 2 1381.

2763. Thats 3 3 307.

2764. Thats 2 2 691.

Jerry is a retired taxi driver from Tucson, Arizona with Asperger syndrome. He has a ruddy complexion and small blue eyes, his large forehead sliced by a diagonal comb of dark blond hair. He likes birds as well as numbers, and when we met he was wearing a flowery red shirt with a parrot on it. We were sitting in his living room, together with a cockatoo, a dove, three parakeets and two cockatiels, which were also listening to, and occasionally repeating, our conversation.

As soon as Jerry sees a big number, he divides it up into prime numbers, which are those numbers 2, 3, 5, 7, 11 that can only be divided by themselves and 1. This habit made his former job driving cabs particularly enjoyable, since there was always a number on the licence plate in front of him. When he lived in Santa Monica, where licence numbers were four and five digits long, he would often visit the four-storey car park of his local mall and not leave until he had worked through every plate.

In Tucson, however, car numbers are only three digits long. He barely glances at them now.

If the number is more than four digits Ill start to pay attention to it. If its four digits or less, its roadkill. It is! he remonstrated. Come on! Show me something new!

Aspergers is a psychological disorder in which social awkwardness can coexist with extreme abilities, such as, in Jerrys case, an extraordinary talent for mental arithmetic. In 2010 he competed at the Mental Calculation World Cup in Germany having done no preparation. He won the overall title of Most Versatile Calculator, the only contestant to score full marks in the category where 19 five-digit numbers have to be decomposed into their constituent primes in ten minutes. No one else got even close.

Jerrys system for breaking down large numbers is to sieve out the prime numbers in ascending order, extracting a 2 if the number is even, extracting a 3 if it divides by three, a 5 if it divides by five, and so on.

He raised his voice to a yell: Oh yeah, were sievin, baby! He started moving his body around: Were on stage. Throw those numbers out, crowd, and well sieve em for ya! Yeah! Jerry and the Sievers!

Ive got a pair of sievers, interrupted his wife, Mary, who was sitting on the sofa next to us. Mary, a musician and former Star Trek extra, also has Aspergers, which is much less common in women than it is in men. A marriage between two people with Aspergers is very rare, and their unconventional romance was turned into the 2005 Hollywood movie Mozart and the Whale.

Sometimes Jerry cannot extract any primes at all from a large number, which means the number is itself prime. When this happens it gives him a thrill: If its a prime number Ive never found before, its kinda like if you were looking for rocks, and youve found a new rock. Something like a diamond you can take home and put on your shelf.