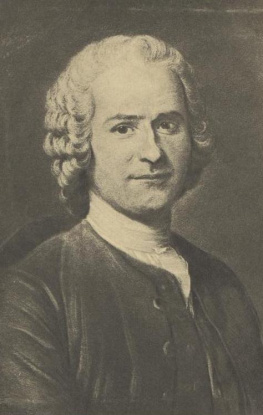

Rousseau - The Social Contract

Here you can read online Rousseau - The Social Contract full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. publisher: The University of Adelaide Library, genre: Science. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:The Social Contract

- Author:

- Publisher:The University of Adelaide Library

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Social Contract: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Social Contract" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Rousseau: author's other books

Who wrote The Social Contract? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

The Social Contract — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "The Social Contract" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

This web edition published by eBooks@Adelaide.

Rendered into HTML by Steve Thomas.

Last updated Monday, November 12, 2012 at 13:00.

This edition is licensed under a Creative Commons Licence

(available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/au/). You arefree: to copy, distribute, display, and perform the work, and to make derivative works under the following conditions:you must attribute the work in the manner specified by the licensor; you may not use this work for commercial purposes;if you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under a license identical tothis one. For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. Any of theseconditions can be waived if you get permission from the licensor. Your fair use and other rights are in no way affectedby the above.

eBooks@Adelaide

The University of Adelaide Library

University of Adelaide

South Australia 5005

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/r/rousseau/jean_jacques/r864s/index.html

Last updated Monday, November 12, 2012 at 13:59

http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/r/rousseau/jean_jacques/r864s/contents.html

Last updated Monday, November 12, 2012 at 13:59

I MEAN to inquire if, in the civil order, there can be any sure and legitimate rule of administration, men being takenas they are and laws as they might be. In this inquiry I shall endeavour always to unite what right sanctions with whatis prescribed by interest, in order that justice and utility may in no case be divided.

I enter upon my task without proving the importance of the subject. I shall be asked if I am a prince or a legislator,to write on politics. I answer that I am neither, and that is why I do so. If I were a prince or a legislator, I shouldnot waste time in saying what wants doing; I should do it, or hold my peace.

As I was born a citizen of a free State, and a member of the Sovereign, I feel that, however feeble the influence myvoice can have on public affairs, the right of voting on them makes it my duty to study them: and I am happy, when Ireflect upon governments, to find my inquiries always furnish me with new reasons for loving that of my own country.

MAN is born free; and everywhere he is in chains. One thinks himself the master of others, and still remains a greaterslave than they. How did this change come about? I do not know. What can make it legitimate? That question I think I cananswer.

If I took into account only force, and the effects derived from it, I should say: "As long as a people is compelled toobey, and obeys, it does well; as soon as it can shake off the yoke, and shakes it off, it does still better; for,regaining its liberty by the same right as took it away, either it is justified in resuming it, or there was nojustification for those who took it away." But the social order is a sacred right which is the basis of all other rights.Nevertheless, this right does not come from nature, and must therefore be founded on conventions. Before coming to that,I have to prove what I have just asserted.

THE most ancient of all societies, and the only one that is natural, is the family: and even so the children remainattached to the father only so long as they need him for their preservation. As soon as this need ceases, the naturalbond is dissolved. The children, released from the obedience they owed to the father, and the father, released from thecare he owed his children, return equally to independence. If they remain united, they continue so no longer naturally,but voluntarily; and the family itself is then maintained only by convention.

This common liberty results from the nature of man. His first law is to provide for his own preservation, his firstcares are those which he owes to himself; and, as soon as he reaches years of discretion, he is the sole judge of theproper means of preserving himself, and consequently becomes his own master.

The family then may be called the first model of political societies: the ruler corresponds to the father, and thepeople to the children; and all, being born free and equal, alienate their liberty only for their own advantage. Thewhole difference is that, in the family, the love of the father for his children repays him for the care he takes ofthem, while, in the State, the pleasure of commanding takes the place of the love which the chief cannot have for thepeoples under him.

Grotius denies that all human power is established in favour of the governed, and quotes slavery as an example. Hisusual method of reasoning is constantly to establish right by fact. It would be possibleto employ a more logical method, but none could be more favourable to tyrants.

It is then, according to Grotius, doubtful whether the human race belongs to a hundred men, or that hundred men to thehuman race: and, throughout his book, he seems to incline to the former alternative, which is also the view of Hobbes. Onthis showing, the human species is divided into so many herds of cattle, each with its ruler, who keeps guard over themfor the purpose of devouring them.

As a shepherd is of a nature superior to that of his flock, the shepherds of men, i.e., their rulers, are of a naturesuperior to that of the peoples under them. Thus, Philo tells us, the Emperor Caligula reasoned, concluding equally welleither that kings were gods, or that men were beasts.

The reasoning of Caligula agrees with that of Hobbes and Grotius. Aristotle, before any of them, had said that men areby no means equal naturally, but that some are born for slavery, and others for dominion.

Aristotle was right; but he took the effect for the cause. Nothing can be more certain than that every man born inslavery is born for slavery. Slaves lose everything in their chains, even the desire of escaping from them: they lovetheir servitude, as the comrades of Ulysses loved their brutish condition. If then thereare slaves by nature, it is because there have been slaves against nature. Force made the first slaves, and theircowardice perpetuated the condition.

I have said nothing of King Adam, or Emperor Noah, father of the three great monarchs who shared out the universe,like the children of Saturn, whom some scholars have recognised in them. I trust to getting due thanks for my moderation;for, being a direct descendant of one of these princes, perhaps of the eldest branch, how do I know that a verificationof titles might not leave me the legitimate king of the human race? In any case, there can be no doubt that Adam wassovereign of the world, as Robinson Crusoe was of his island, as long as he was its only inhabitant; and this empire hadthe advantage that the monarch, safe on his throne, had no rebellions, wars, or conspirators to fear.

THE strongest is never strong enough to be always the master, unless he transforms strength into right, and obedienceinto duty. Hence the right of the strongest, which, though to all seeming meant ironically, is really laid down as afundamental principle. But are we never to have an explanation of this phrase? Force is a physical power, and I fail tosee what moral effect it can have. To yield to force is an act of necessity, not of will at the most, an act ofprudence. In what sense can it be a duty?

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «The Social Contract»

Look at similar books to The Social Contract. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book The Social Contract and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.