The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

For Edith and Andrew, onwards and outwards

Contents

Ocean

I return to find secrets. I return to rob them.

Robert Duncan

Two Men Smoking

and sees all things and to him

are presented at night

the whispers of the most flung shores

from Gloucester out

Ed Dorn

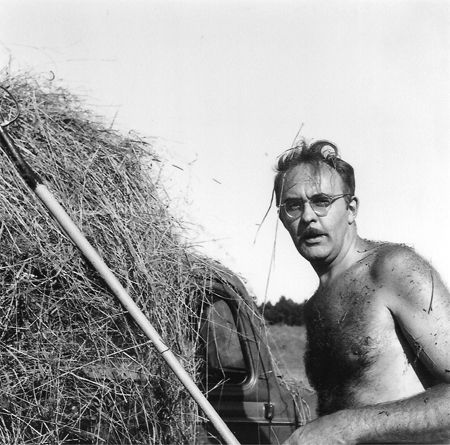

It was the season of autumn ghosts, a dampness in the soul. 2011 and London had lost its savour. A good step beyond midway through my dark wood of the world, I came to America, hoping to reconnect with the heroes of my youth. The largest, the most light-occulting of all the giants, that earlier race, was Charles Olson: poet, scholar and last rector of Black Mountain College. This establishment, a scatter of buildings beside a lake in North Carolina, now imploded, bankrupt, seemed to us a Valhalla of all the talents: Josef Albers, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Robert Rauschenberg, Buckminster Fuller, Robert Duncan, Robert Creeley, Ed Dorn. Pick up the traces anywhere you choose, through fugitive magazines or literary gossip, and they lead back to one man. Olson knew, better than most, that his chosen territory, the Eastern Seaboard, the whaling ports, was once connected to Scotland. And long before Prince Henry Sinclair, the Earl of Orkney, crossed the Atlantic, island-hopping in 1398 , to bring back stories of infinite forests and their natives, and to leave his mark stamped on a rock. The native Micmac Indians, according to some authorities, recognized the tall voyager as their man-god, Glooscap. Kulskap was the first, first and greatest, to come into our land, sang the tribal poet. He was sober, grave, and good. The big man walked on the backs of whales. One of Olsons youthful disciples, Peter Anastas, carried out proper research into Glooscap; his heritage, the archaeological scratchings, the subsistence life in shack and trailer park endured by the last of the first people in this unyielding place.

Glooscap the man becomes Gloucester the town. By sound, by sonar echo, by necessity. Olson, writing about his childhood and his father, the Worcester mailman, calls the story Stocking Cap. With some hope of payment, he sent it to The New Yorker in February 1948 . It was rejected. Glooscap, Stocking Cap. A nod to elective Swedish ancestors, to Vikings. Cutting holes in the ice, winter fishing: father and son. I loved the old photograph used on the cover of Olsons memoir, The Post Office : that stern, bulb-headed baby emerging from a sack of letters, hard against his fathers pounding heart. Two figures from a race of huge, raw-boned immigrants, studio-captured against a painted pond, a forest clearing. I wanted it to be so. I needed a new mythology to shield against the sense of loss and hanging dread inherent in the invasion and dissolution of my familiar London ground; forty years learning where to walk and a few months to lose it all. Go back then into uncertainty, ocean-venturing exchanges. Ed Dorn, one of the sharpest and most independent of Olsons Black Mountain students, and just about the only one who bothered to graduate, characterized Gloucester as somewhere settled by people from remote islands who knew how to build fences and stone walls. Thats one reason why New England is really there, he said.

Its a tough one, Olson replied, laying out the American West as Dorns field of study. One things sure: economics as politics as money is a gone bird.

All poetry, a now-obsolete (and stronger for that) form, Dorn suggested, derived from The Iliad or The Odyssey. Either we stay put, dig in, battle with our gods, or we move, drift, detour: move for the sake of moving. Jack Kerouacs On the Road is precisely what it says: it goes on as long as the roll of paper lasts. Olson was formidable in combining the two archetypal sources: he excavated the particulars of his adopted town and he contemplated the restless sea. Without leaving his high window, he would drive off spleen by charting the madness of those who ventured on the watery part of the world. He began with Herman Melville. Curse me with truth. Call me Ishmael.

* * *

Today, quite suddenly, the sun breaks through; I follow Olsons obliterated footprints. There is the long shadow of a drowned man on the beach. And he is walking, rolling heavy shoulders. You have to be dead yourself, more than a little, to register him. The Atlantic, on this precious morning, is blameless; every pebble visible, an invitation to stripping off and striking out. But it wont happen, not now. Not ever.

I come along the curve of the esplanade they call boulevard, from Fort Point, tramping in suspended excitement, with watering eyes, above a beach I know so well; this place I have never been, even in sleep: Gloucester, Massachusetts. Late October, season of perfect storms. Even the houses of the wealthy, set back from the shore, are not immune. Buffalo waves break free of the jet stream; steepling rollers, in a shatter of wet glass, spout and smash, upturning cars, rearing over breakfast bars, their panoramic windows crusted with salt, rattled by scouring grains of sand. You are embedded here, at a small table, with your squirting egg and crisped bacon, your coffee refill. A few, mid-morning, comfortably fleshed, warm-shirted citizens stare out on the rain, the road, the shore, making desultory conversation. Some do not turn their heads. More politics, another dying year. The decline of the fishing fleet. Boarded-up computer-repair shops. Banks like temples from an earlier granite era. Barriers erected around City Hall, the civic centre. Tactful marine presentations in Cape Ann Museum. Safe rocks and secure objects: rescued boats, fading portraits. The original statue of Our Lady of Good Voyage, that draped and crowned votive figure brought in from the church roof, now shockingly out of scale in a dim chamber. Huge hands, this woman of wood: a fish-gutter supporting a model twin-masted vessel.

* * *

Olsons car didnt do reverse. When a friend, sent out from the upstairs apartment with the great view, on the point, right over the Inner Harbor, to fetch cigarettes and whisky for another all-night session, sandwiches even, asked, with some trepidation, how Charles managed this thing, navigating the icy streets in a defective motor, the poet said: Never go backwards. Arm raised so! gloved fist clamped to fence, Russian cap and trailing coat. That way. Always that way now. Inland, brother. At the end of the poem, of the long emphysemic drag of breath and tumult, the headaches, bunker fevers, heartsick losses, he turned away from the sea. Found a nest in which to die. They carried him, complaining, head first, to the ambulance; crabbed, harpooned. Strike out, stride forward. Then, over Brooklyn Bridge, quoting Lear until the hurt was too much and he gripped his companions arm, white, asking for painkillers, and they gave him water. The words on the wall of the hut, the Gloucester Writers Center, where I was now lodged: my wife my car my colour my self. Precisely scored gaps for taking breath.

* * *

In the town museum I discovered a painting, studio-posed, reconfiguring some forgotten classical tableau. Rocks. The virgin New England shore of green scrub, grey clouds. Three people: two women and a man. I dont want to know who painted it. A clothed girl, dark hair depending from a summer hat, props herself on her left arm; she sprawls, shoes off, confronting the bathing-suited figure of a conspicuously fit young man with rather effeminate tresses and supplicant lips. At the edge of the composition, clutching a thick black branch, is another woman, a little older perhaps, more obviously mythological; smooth, bare leg emerging from a long white wrap. Sexual tension, subdued but palpable, plays across the interval between the solitary standing figure and the transfixed couple. The gash dividing the spread of rocks is matted with pubic moss. The couple facing us, recovered from their swim, near-naked but bone dry, make-up intact, confront the clothed girl, whose elbow is scabbed and raw: an orgy postponed. And hung in a corner of a museum nobody visits. As competent and pointless as Augustus John.

Next page