Table of Contents

For Ted Taylor

Itdoomed the mammoths, and it began the setting of that snare that shallcatchthe sun....

H.G. WELLS, 1914

PREFACE

Bel-Air

In1957,tail fins, not seat belts, were standard equipment on American cars.Tail finsreached a peak in popularity with the 1957 Chevrolet Bel-Air. Poweredby a235-cubic-inch straight six or a 283-cubic-inch V-8, with either manualoverdrive or powerglide automatic transmission, the Bel-Air had atwo-toneexterior, accented by anodized aluminum suggesting space-age LosAngeles ratherthan iron-age Detroit. Optional equipment, besides seat belts, includedpowerwindows, six-way power seats, and a built-in electric razor. TheRussians wereahead in space, but General Motors was ahead on the road.

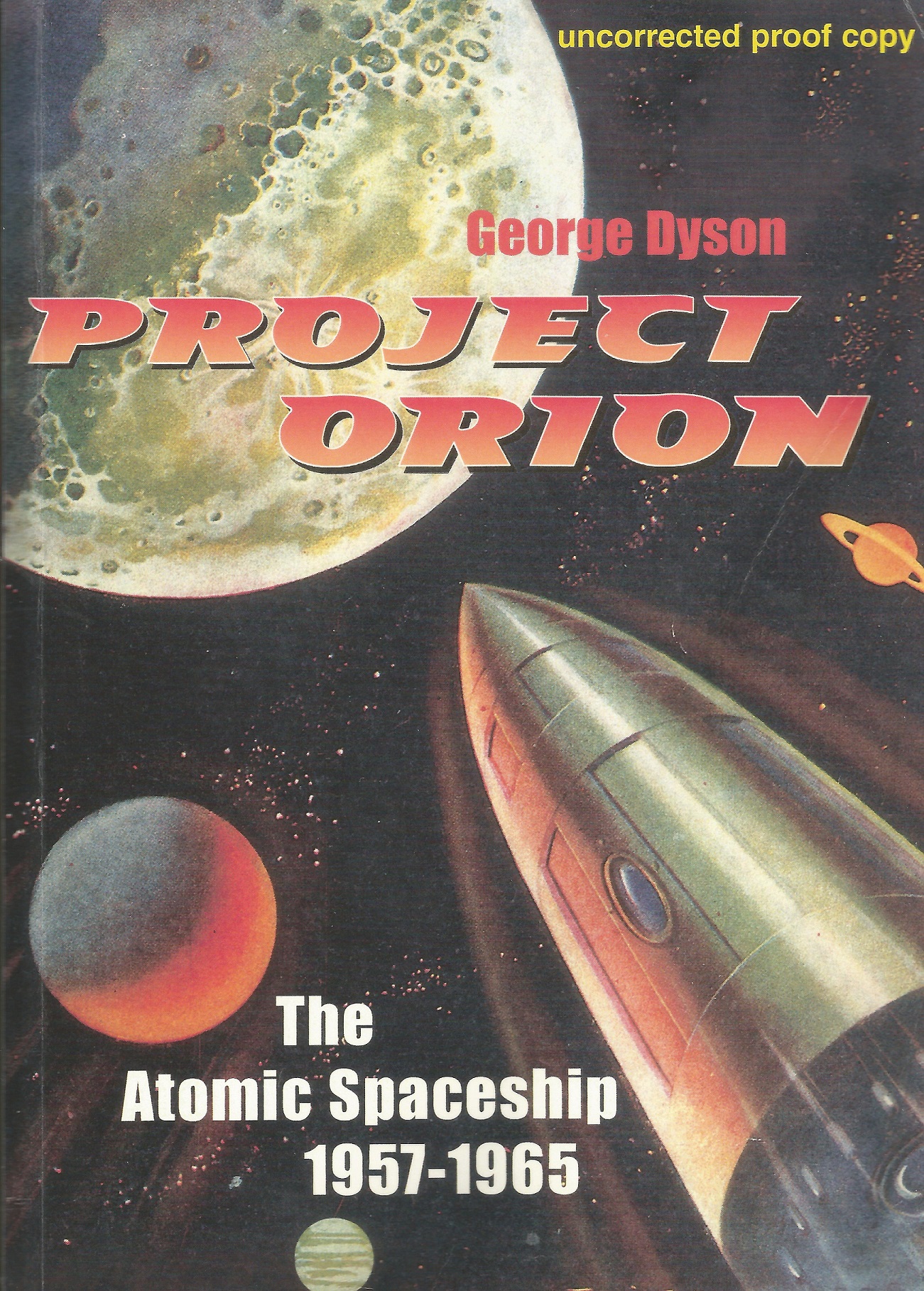

Thisbookis the story of Project Orion. In 1957, a small group of scientists,led byphysicist Theodore B. Taylor and including my father, Freeman J. Dyson,launcheda serious attempt to build an interplanetary spaceship propelled bynuclearbombs. This account, as best as I can reconstruct it, is the story myfathercould tell me only in fragments at the time.

Orionwas a sibling of both Sputnik and theChevrolet Bel-Air. When my father joined Project Orion, he was drivinga 1949Ford. After a year in La Jolla, California, it was time to give up theFord."Our poor old car finally gave up the ghost," he reported in hisweekly letter home. "So on Friday night we took the old car out for itslast run. We went to a big car-dealer in San Diego. We looked at a lotof cars,drove three, and finally bought a 2-year-old Chevrolet at 9 P.M." A turquoise and white 1957Bel-Air.

Toafive-year-old from New Jersey, La Jolla (the jewel) was paradise found.GeneralAtomic, the project's contractor, provided a house with a swimming poolandcitrus orchard, draped in bougainvillea and overlooking the PacificOcean,which we scanned at sunset for the green flash. Winter swells brokeover thereef at Windansea, where a surfing culture as tenacious as the inshorekelpbeds had taken hold. Theodore Geisel, better known as Dr. Seuss,visited ourthree-room schoolhouse at La Jolla Cove. Abalone big enough to resist atireiron could be gathered at low tide. My father and later mythirteen-year-oldsister Katarina joined the local glider club and spent Saturdays tryingto stayaloft in a fabric-covered sailplane winched into the updrafts above thecliffsat Torrey Pines. Jack Kerouac published On the Road.

Thetailfins on the Chevrolet matched those on the Atlas intercontinentalballisticmissiles that Convair Astronautics, a branch of the same corporatefamily asGeneral Atomic, was building at a new $40 million facility four milesinland.In July of 1958 Convair held an open house, providing free hot dogs andthehourly flight of a model ICBM, which, the local paper announced, "willemit a trail of smoke and will complete its trip with a big red flash,simulating the detonation of a warhead." Real Atlas missiles, with arangeof 5,000 miles, carried thermonuclear warheads yielding one hundredHiroshimaseach. The delivery of hydrogen bombs to civilian targets was celebratedwith anopen house, while Orion, a spaceship that would use bombs to deliverciviliansto Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn, was so encumbered by secrecy that untilJuly of1958 even the existence of the project remained publicly unknown.

Muchof the record of Project Orion is stillclassified "SecretRestricted Data" even though most of what kept theproject secret in 1958 is now in the open, except for a few specifictechnicaldetails. Any danger of Project Orion literature being used fordestructivepurposes is outweighed by the possibility that knowledge of Orion maybe usefulin ways that we cannot now predict or understand. Eventually, we willoutgrowthe use of nuclear energy as a weapon. Project Orion is a monument tothose whoonce believed, or still believe, in turning the power of these weaponsintosomething else.

Allthepeople I visited or revisited in gathering this account believe theycontributed to a dream that was nonetheless important for havingfailed. Theyears they spent working on Orion were the most exciting of theirlives. Wouldthey do it again? Definitely yes. Should we do it now? Probably not.

"Wehad a wonderfully free time, before any of that fallout stuff camedown,"says Orion's lead experimentalist, Brian Dunne. "It was a crazy era.Allof our values were tweaked because of the cold war. It was a closedsociety,and all kinds of strange ideas were able to grow."

1

Sputnik

OnOctober4, 1957, Earth's first artificial satellite, weighing 184 pounds, waslaunched.Sputnik I circled the earth every 90 minutes for the nextthree months.Sputnik II followed on November 3 and weighed 1,120 pounds,includingLaika, the pioneer of space-faring dogs. Earth's third artificialsatellite wassent into orbit on January 31, 1958. Launched by a 32-ton Jupiter-Crocketbuilt by the Chrysler Corporation, Explorer I weighed31 pounds.

Theracefor space had begun. In Washington, D.C., the Advanced ResearchProjects Agency(then ARPA, now DARPA) was given a small office in the Pentagon andassignedthe task of coordinating United States effortsboth civilian andmilitarytocatch up. NASA did not exist until July of 1958. All three branches oftheUnited States military had competing designs on space. "If itflies,that's our department," claimed the Air Force. "But they're called spaceships,"repliedthe Navy. "OK, but the Moon is high ground," answered the Army, which hadalready enlisted rocketpioneer Wernher von Braun.

Sputnikcaught the American public, but notthe United States aerospace establishment, by surprise. Americanscientistswere well aware of the Soviet effort and several United States spaceprogramsincluding the Atlas and Titan Intercontinental BallisticMissiles, theExplorer and Vanguard satellite programs, the Rover nuclear rocketproject atLivermore and Los Alamos, and even plans for a moon landingwere underwaybefore the Russian Sputniks went up. ARPA's mission was to consolidateexistingaerospace projects, differentiate military from civilian objectives,andconsider all alternatives, however far-fetched. Things nuclear wereviewed withenthusiasm. This was the era of unrestricted atmospheric bomb tests,with theequivalent of several thousand Hiroshimas being exploded from one yearto thenext.

OneofARPA's alternatives, code-named Project Orion, was an interplanetaryspaceshippowered by nuclear bombs. Orion was the offspring of an idea firstproposed, asan unmanned vehicle, by Los Alamos mathematician Stanislaw Ulam shortlyafterthe Trinity atomic bomb test at Alamogordo, New Mexico, on July 16,1945. Itwas typical of Ulam to be thinking about using bombs to delivermissiles, whileeveryone else was thinking about using missiles to deliver bombs.

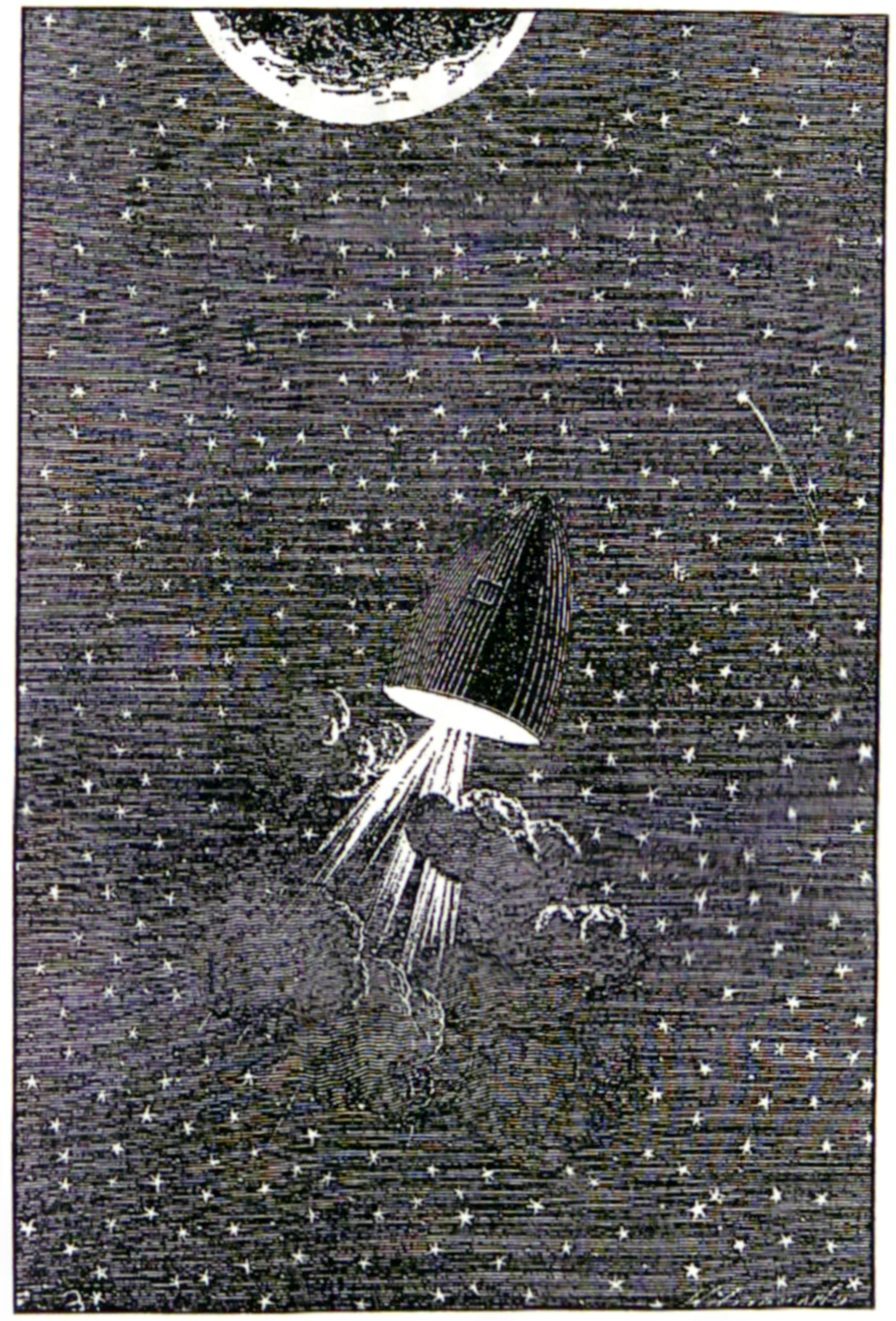

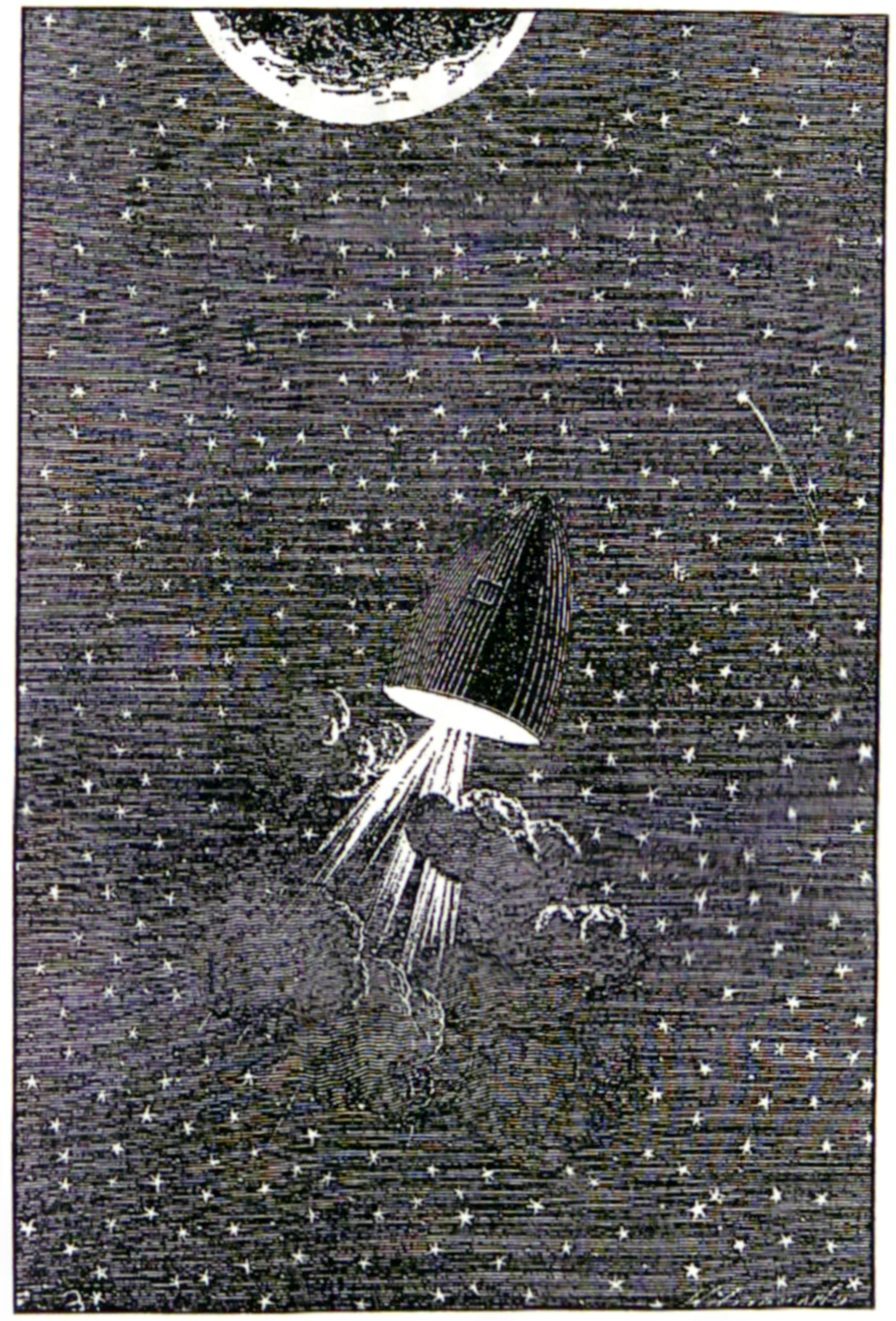

Tovisualize Orion, imagine an enormous one-cylinder external combustionengine: asingle piston reciprocating within the combustion chamber of emptyspace. Theship itself, egg-shaped and the height of a twenty-story building, isthepiston, armored by a 1,000-ton pusher plate attached by shock-absorbinglegs.The first two hundred explosions, fired at half-second intervals, witha totalyield equivalent to some 100,000 tons of TNT, would lift the ship fromsealevel to 125,000 feet. Each kick adds about 20 miles per hour to theship'svelocity, an impulse equivalent to dropping the ship from a height of15 feet.Six hundred more explosions, gradually increasing in yield to 5kilotons each,would loft the ship into a 300-mile orbit around the earth. "I used tohave a lot of dreams about watching the flight, the vertical flight,"saysTed Taylor, Ulam's younger colleague who founded Project Orion and, asthedesigner of both the smallest and the largest fission bombs in theUnitedStates repertoire, was uniquely qualified to dream where nightmaresalone haveotherwise led. "The first flight of that thing doing its full missionwould be the most spectacular thing that humans had ever seen."

Next page