All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by reviewers, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of the same without the permission of the publisher is prohibited.

Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the authors rights is appreciated.

Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use or anthology should send inquiries to Permissions c/o Quercus Publishing Inc., 31 West 57th Street, 6th Floor, New York, NY 10019, or to .

INTRODUCTION

IMAGING THE INFINITE

Ever since the first stargazers turned their eyes to the heavens, humans seem to have had an urge to record what they saw in the night sky. Art and astronomy have been intimately linked for thousands of years, far back into prehistory. Telltale dots, some 15,000 years old, painted among the Ice Age animals on the walls of the famous Lascaux caves, appear to relate to star patterns we still recognize today. Meanwhile, under certain conditions, the rising Moon shines down the great passage tomb of Knowth, in Irelands County Meath, to illuminate an ancient image of itself the earliest known lunar map, carved into a 5,000-year old megalithic stone known as Orthostat 47.

By the dawn of recorded history, representations of the constellations, stars and planets are everywhere, ranging from more or less accurate, maps of the heavens, presumably intended for practical use, to more fanciful forms such as the familiar figures of the zodiac (originating in ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt) and the planetary gods of the classical world. Later in the first millennium ad, Arab astronomers took the accuracy and beauty of their hand-drawn star maps to new heights, and medieval European scholars built on their achievements to create wonderful celestial spheres and charts.

But it was to be the dawn of telescopic astronomy that changed everything, transforming the sky from a single vast canvas for painting stories on a cosmic scale, to a mounting board for countless individual wonders, each of which could now be studied discretely and in far more detail. Galileos first act, on viewing the satellites of Jupiter, the mountains of the Moon and the phases of Venus for the first time around 1609, was to record them in ink drawings that could ultimately be circulated to share his discoveries.

For the next four centuries, draughtsmanship became an essential part of the astronomers skillset, the sketchbook almost as important as the telescope. Astronomical art rapidly developed its own vocabulary: since most were working rapidly with pencil and paper, sketching objects that rapidly drifted out of the eyepiece as the sky rotated through the night, it made sense to mark stars as black pencil-dots, and patchy areas of light as shade. To modern eyes, the results are irresistibly reminiscent of photographic negatives. Skilled engravers could later take such sketches and invert them to produce prints that gave a more familiar representation of the sky, but as often as not, astronomers knew how to interpret their colleagues and rivals recordings of the sky without such intermediaries.

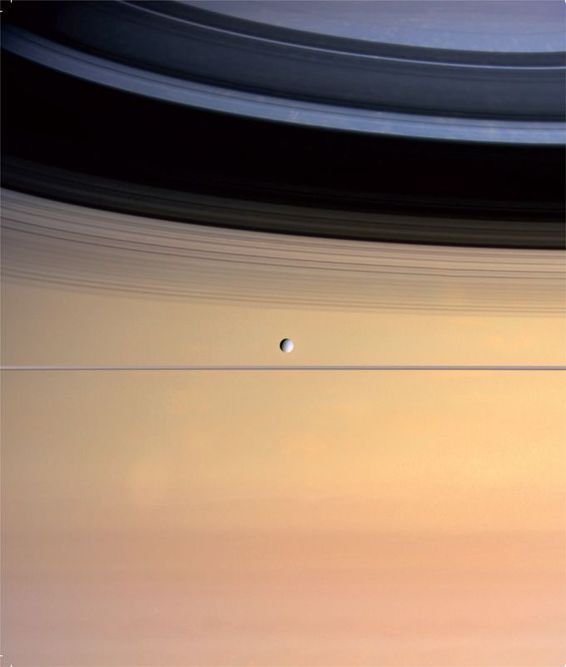

As telescopes improved in both size and quality, they brought new celestial objects into view for the first time. The increased size of lenses or mirrors allowed them to sweep up far more of the precious light rays coming from distant parts of the cosmos than the human eye ever could alone, bringing fainter objects within view. Along with optical improvements it also led to increased resolution the ability to divide narrowly separated objects and distinguish fine detail. A handful of nebulous objects and tight star clusters had been known since ancient times, but the 18th century saw their numbers grow rapidly.

From 1771, French astronomer Charles Messier made the first attempt to catalogue such objects though in truth his prime concern was to avoid confusion with faint comets that he was more eager to find. Nevertheless, Messiers catalogue led astronomers to realize that there were several distinct types of nebulous object, some of which clearly resolved themselves into a multitude of stars under high magnifications, while others remained unresolvable perhaps because they were truly gaseous, or perhaps simply because their stars were too numerous and far away.

The art of the astronomical drawing reached its apogee in the mid-1800s, thanks largely to the work of one man. William Parsons, Third Earl of Rosse, was a member of the Irish nobility who used the family wealth to build the largest telescope of its time in the grounds of Birr Castle in Irelands County Offlay. The Leviathan of Parsonstown, as it became known, was completed in 1845 and boasted a mirror with a 183-centimetre (72-in) diameter. It was only superseded, by the 2.5-metre (100-in) Hooker Telescope at Californias Mount Wilson Observatory, in 1917. Parsons set out to revisit the nebulae catalogued by Messier and others, drawing them in exquisite detail and gaining new insights into their structure and true nature. In 1850, he published his researches at Londons Royal Society, revealing that, for instance, that he had identified delicate spiral structures in several nebulae, and resolved others into stars for the first time. After Rosses death Danish-Irish astronomer J.L.E. Dreyer put the Leviathan to good use from 187478 while compiling his New General Catalogue of nebulae and star clusters. NGC numbers are today applied to most reasonably bright non-stellar objects.

But even before Rosse had published his discoveries, new technology was threatening to revolutionize the science of astronomy. The first process for preserving images using light-sensitive chemicals was announced by French inventor Louis Daguerre in 1839, but even before then, he had used this technique to capture the first photographic view of the Moon. Daguerres image was faint and fuzzy, but in 1840 US chemist and physician J.W. Draper repeated the experiment with much more success. Early photographic plates were famously slow to respond to light (Drapers image required a 20-minute exposure) and so the first astrophotographs struggled to compete with normal eyesight, but they showed instant promise as a way of providing a permanent, objective record of the heavens. The technology developed rapidly, and an important breakthrough came in 1863 when two Britons, William Allen Miller and William Huggins, used photography to capture and study the faint rainbow-like spectra produced by stars, paving the way for the study of their chemistry (see ) to capture the light from previously undetected stars.