THE MIRACLE OF ANALOGY

or The History of Photography, Part 1

KAJA SILVERMAN

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

STANFORD CALIFORNIA

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

2015 by the Board of Trustees of the Leland Stanford Junior University. All rights reserved.

: Abelardo Morell, Camera Obscura: Courtyard Building, Lacock Abbey, England, 2003. Silver-gelatin print. Image Abelardo Morell, courtesy of Edwynn Houk Gallery, New York.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Silverman, Kaja, author.

The miracle of analogy, or, The history of photography / Kaja Silverman.

volumes cm

Complete in two volumes.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-8047-9327-8 (v. 1 : cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-8047-9399-5 (v. 1 : pbk.: alk. paper)

1. PhotographyHistory. I. Title. II. Title: Miracle of analogy. III. Title: History of photography.

TR15.S49 2015

770dc23

2014036175

ISBN 978-0-8047-9400-8 (electronic)

Designed by Bruce Lundquist

Typeset at Stanford University Press in 10/15 Adobe Caslon Pro

For those I love.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Since I embarked on this book while teaching at Berkeley, I want to thank those who formed my community there, and with whom I shared so much, both personally and professionally: Wendy Brown, Judith Butler, T. J. Clark, Samera Esmeir, Ramona Naddaff, and Anne Wagner. Because I wrote most of the book since arriving at Penn, I also want to thank my colleagues and students in the History of Art for welcoming me so warmly, and making me so glad to be here. Warm thanks are due as well to Aaron Levy at the Slought Foundation and the curators at the Institute of Contemporary Art for our rich and energizing collaborations.

I discussed many of the ideas in this book with Leo Bersani, David Eng, Homay King, Erica Levin, Danny Marcus, and Rob Miotke, all old friends and trusted interlocutors. The manuscript benefited enormously from the written feedback of an exceptional group of readers: George Baker, Brooke Belisle, Natalia Brizuela, Todd Cronan, Jacques Khalip, and Andrew Moisey. I am especially indebted to Andr Dombrowski, who not only patiently listened to me rehearse every version of every idea in the book, but also pored over a late draft and provided me with an invaluable commentary.

I wouldnt even be at Penn if it were not for the generosity of Keith L. and Katherine Sachs, dear friends and art collectors extraordinaire. My life has been enriched beyond compare by the gift of a Mellon Distinguished Achievement Award, whichamong many other thingscovered the expenses related to this book.

Thanks are also due to George Conn, who worked tirelessly on the permissions for this book; Kaelin Jewell, who formatted the manuscript; George, Kaelin, and Amy Gillette, who checked all of the citations; and Jan McInroy, who graciously agreed to serve once again as my copyeditor.

Finally, I want to thank Emily-Jane Cohen, my editor at Stanford University Press, for her ongoing and unfailingly intelligent support of my work.

INTRODUCTION

WE HAVE GROWN accustomed to thinking of the camera as an aggressive device: an instrument for shooting, capturing, and representing the world. Since most cameras require an operator, and it is usually a human hand that picks up the apparatus, points it in a particular direction, makes the necessary technical adjustments, and clicks the camera button, we often transfer this power to our look. The standardization of this account of photography marked the beginning of a new chapter in the history of modern metaphysicsthe history that began with the cogito, which seeks to establish man as the relational center of all that is, and whose fundamental event is the conquest of the world as a picture. His camera-wielding successor could picture the worldor so he claimedwithout closing his eyes.

When we challenge this account of photography, it is usually by appealing to the mediums indexicality. Since an analogue photograph is the luminous trace of what was in front of the camera at the moment the photograph was made, we argue, it attests to its referents reality, just as a footprint attests to the reality of the foot that formed it. The philosopher from whom the concept of indexicality derivesCharles Sanders Peirceuses it to describe both signs that are linked to an unfolding situation or event and those that are linked to a prior situation or event. I see a man with a rolling gait. This is a probable indication that he is a sailor... , he writes in What Is a Sign? A weathercock indicates the direction of the wind. A sun-dial or a clock indicates the time of day... [and] a tremendous thunderbolt indicates that something considerable happened, though we may not know precisely what the event was.

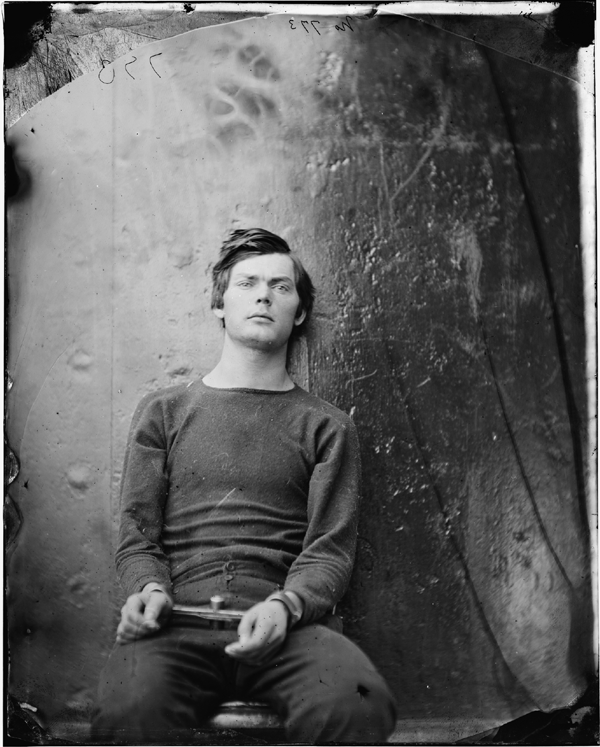

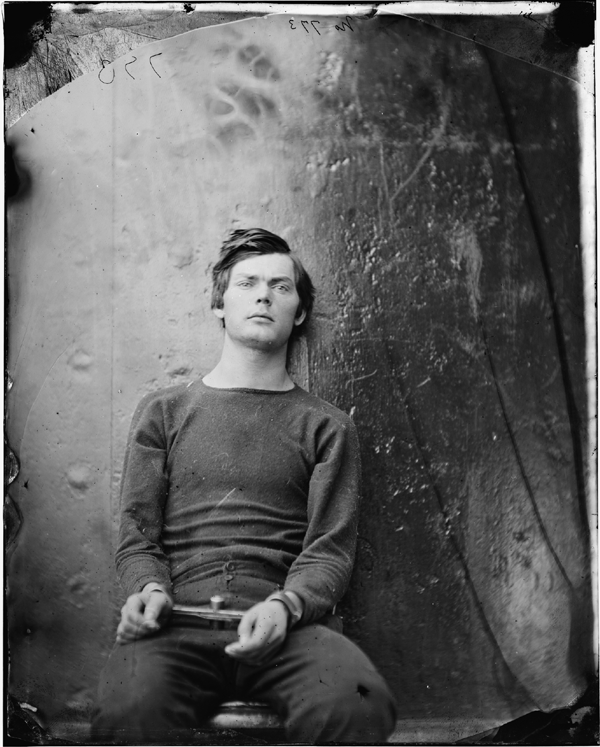

Figure 1. Alexander Gardner, Washington Navy Yard, D. C. Lewis Payne, in sweater, seated and manacled, 1865. Albumen print from collodion wet-plate negative. Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

Discussions of photographic indexicality, though, always focus on the past; an analogue photograph is presumed to stand in for an absent referentone that is no longer there.

Many leftist artists and writers have gravitated to this account of the photographic image. For some, like Walter Benjamin and the young Hans Haacke,

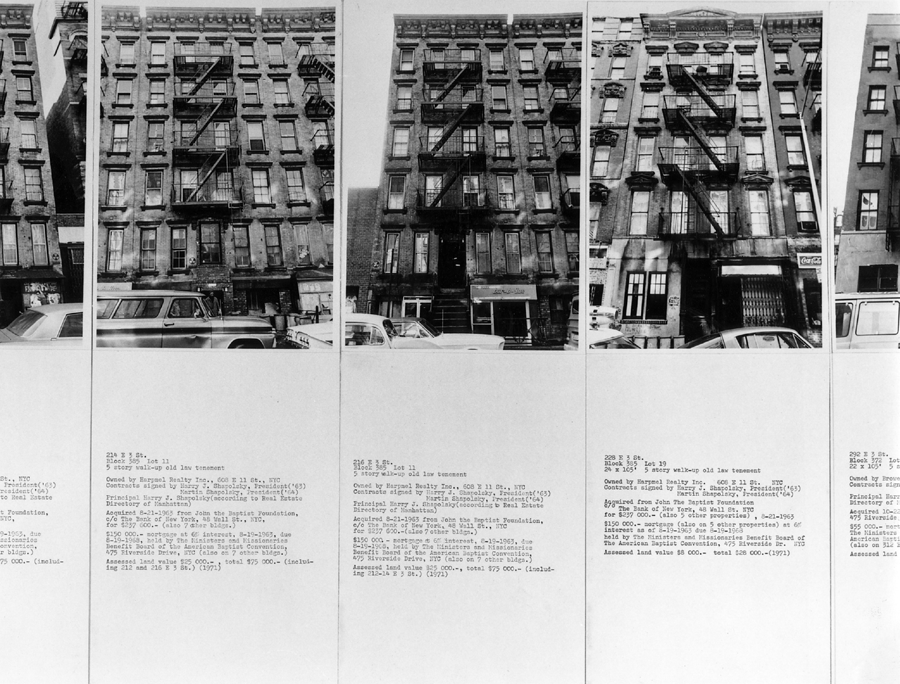

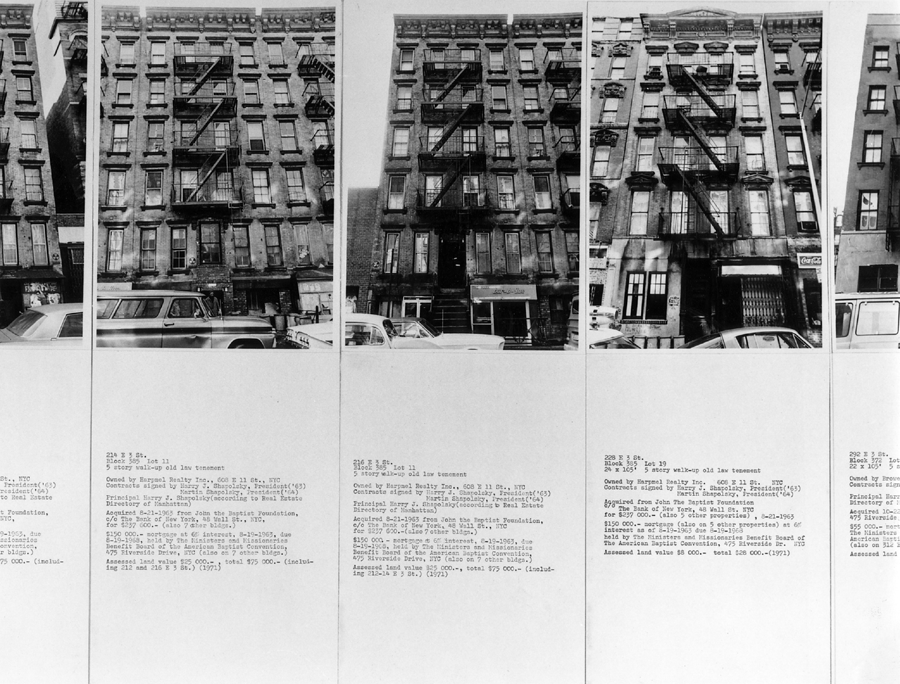

Figure 2. Hans Haacke, Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real Time Social System, as of May 1, 1971. Photographic installation. Reprinted with permission of the artist. Hans Haacke/Artists Rights Society (ARS).

But although there have been pitched battles between those who champion the evidentiary value of the photographic image and those who emphasize its constructedness, the former is only another way of overcoming doubt. If a photograph can prove what was, then it is the royal road to certaintythe means through which we know and judge the world. And if what we see when we look at a photographic image is unalterable, then there is only one thing we can do: take what is dead or going to die into our arms. Barthess mobilization of the future perfect in this and other passages in Camera Lucida renders the future as unchanging as the past. This account of the photographic image consequently both expresses and contributes to the political despair that afflicts so many of us today: our sense that the future is all used up.

In 1931, Benjamin wrote an essay about this malaise, which he calls left-wing melancholy. It is the attitude, he writes, to which there is no longer, in general, any corresponding political action. It affects those who are remote from the process of production.of capitulating to it himself. Not only was he an unemployed Jewish intellectual living in a country that he would soon be forced to flee, but he, too, was remote from the process of production, since he was a member of the bourgeoisie.

Next page