published by

Princeton Architectural Press

37 East Seventh Street

New York, New York 10003

Visit our website at www.papress.com.

2007 Princeton Architectural Press

All rights reserved

10 09 08 07 4 3 2 1 First edition

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright. Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

editing

Nicola Bednarek

design

Andy Pressman / 212box

typefaces

Kievit family, designed by Mike Abbink

special thanks to

Nettie Aljian, Dorothy Ball, Janet Behning,

Becca Casbon, Penny (Yuen Pik) Chu, Russell Fernandez, Peter Fitzgerald, Wendy Fuller, Jan Haux, Clare Jacobson, John King, Nancy Eklund Later, Linda Lee, Katharine Myers, Lauren Nelson Packard, Jennifer Thompson, Paul Wagner, Joseph Weston, and Deb Wood of Princeton

Architectural Press Kevin C. Lippert, publisher

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kopelow, Gerry, 1949

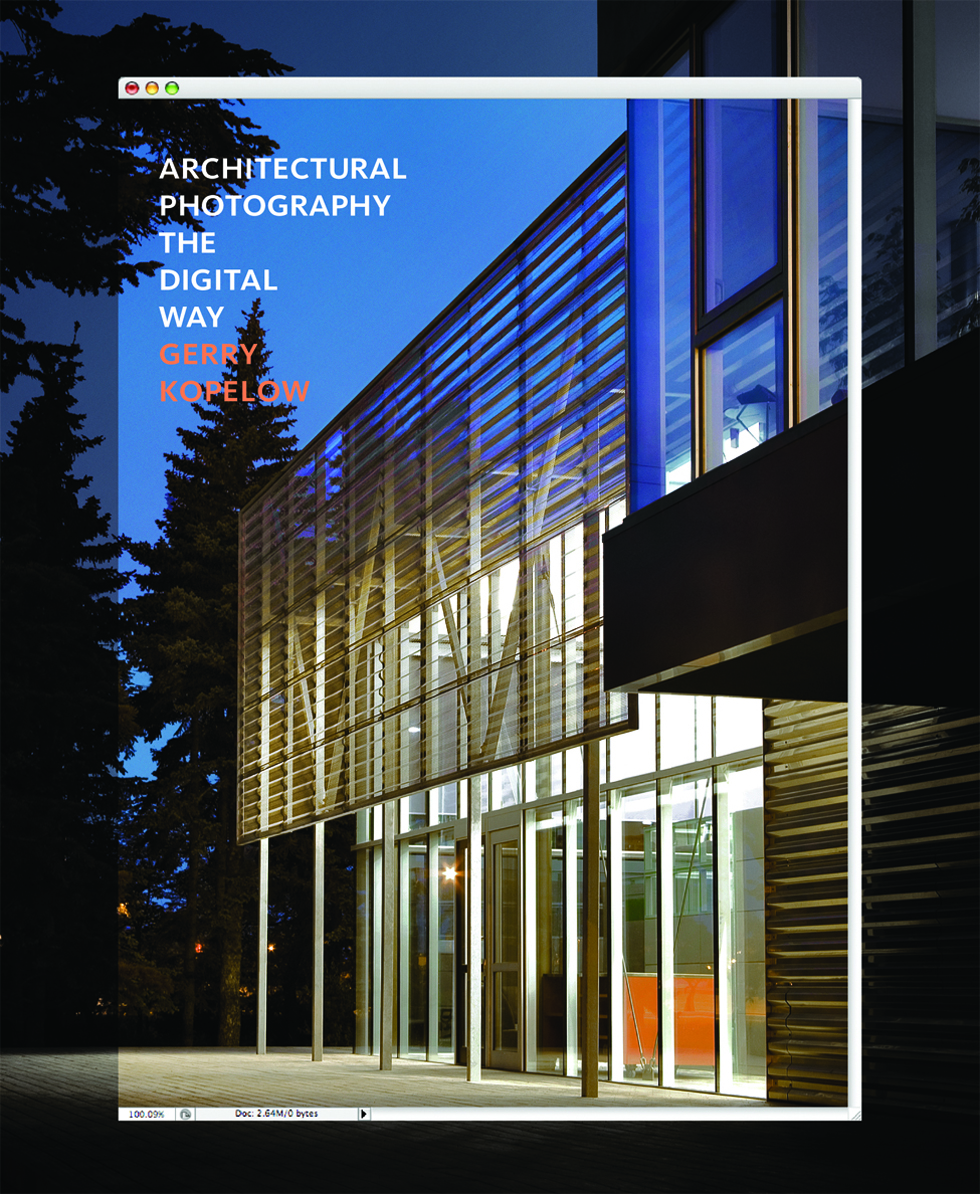

Architectural photography the digital way / Gerry Kopelow.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN-13: 978-1-56898-697-5 (alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 1-56898-697-1 (alk. paper)

ISBN: 978-1-61689-215-9 (digital)

1. Architectural photography.

2. Photography Digital techniques. I. Title.

TR659.K657 2007

778.94dc22

2007004345

For my terrific children, Sacha and Leo, artists both.

contents

As this is being written, it has been more than three years since I last made a commercial image on film. All my painstakingly accumulated large-format, medium-format, and 35-mm film gear is gone because today I shoot exclusively with high-end digital equipment. I am able to carry my entire complement of cameras and lenses over my shoulder, while the rest of my kit, consisting of a modest electronic flash set-up and a tripod, fits easily into a small roller case. The digital revolution is a great liberation. But the wide variety of photo-related digital hardware and software available today can be overwhelming. And of course, the technical revolution has engendered a revolution in shooting and lighting methodologies to match.

The proliferation of design-oriented magazines, desktop publishing, digital imaging, and websites has made well-executed architectural photography ever more important for design professionals. Today all architectural practitioners need to know how to produce high-quality images in order to document, publish, and market their projects. When premium results are required, the first and often the best resource is a professional architectural photographer. While professional photography is expensive, the marketing benefits will usually justify the cost. Nevertheless, establishing an extensive image archive is a slow business, and a return on investment can be a long time coming. The question arises: How can a range of utilitarian and sophisticated photographic needs be satisfied without breaking the bank? The answer is simpledo the work in-house. Of course, an amateur will never be able to compete with a professional all the time, but a well-prepared amateur using a digital single-lens-reflex camera can produce respectable results. This book will teach you how to take successful photos of buildings, inside and out, with digital equipment. Step by step you will learn how to choose the right kind of camera, how to use it effectively, and how to enhance and manipulate your images digitally. As with most crafts, practice is everything, so happy shooting!

High-quality architectural photography fulfills the following characteristics: The image is clear, with an abundance of detail and consistent focus. Its color appears natural and appropriate for the scene. Perspective and point of view are natural and pleasing, and the sun angle,sky conditions, and seasonal variations are appropriate. The subject is portrayedin proper context relative to the site, and the scale of the subject is properly established. To understand how to achieve these goals, we need to start with the fundamentals of digital photography.

A digital camera is a light-tight box that holds a lens and a light-sensitive electronic sensor in precise alignment. The lens projects an image of an object in the real world onto the sensor, which yields an encoded series of electrical potentials. After various mathematical manipulations the signal becomes an electronic analogue of the original optical image. The degree to which a sensor responds to a given amount of light is described by an iso (International Standards Organization) rating. This system was originally established to quantify the characteristics of film, but today we can choose from a range of electronically selectable sensitivities. The higher the iso , the greater the sensitivity iso 3200 is very high while iso 50 is very low. The amount of light that is recorded by the camera has to be regulated to accommodate the characteristics of the sensor. This regulation is achieved with a shutter and a diaphragm.

The shutter is a door through which the light passes. Not too long ago shutters were governed by clockwork mechanisms to open and close automatically for short periods of time (about 1 second to 1/500th of a second) and operated manually for longer periods of time (about 2 to 300 seconds). Modern shutters operate electro-mechanically across a much wider range of precisely controlled intervals.

The diaphragm is a variable aperture, much like the iris of the human eye. The wider it is opened, the more light can pass through the lens. The size of the opening is calibrated in units called f -stops. f -stops are determined by the formula f=fl/a , where fl is the focal length of the lens (the distance from the center of a particular lens to the sensor plane, when the lens is focused on a distant object) and a is the diameter of the lens. Because the f -stop is a reciprocal, a relatively large number means a relatively small amount of light will be transmitted through the lens: f 1.4 is considered large, whereas f 22 is small.

The aperture setting and the shutter speed are inversely related: if the aperture is increased (widened), the shutter speed must be decreased (shortened in duration) and vice versa in order to maintain correct exposure. All digital cameras, of all formats, incorporate a lens, a diaphragm, a shutter, a sensor, and a light-tight box to hold them together.

Architectural photographers need a basic understanding of two camera types: the large-format view camera and the single-lens-reflex ( slr ). The view camera has been around since photography began while the slr is a relatively modern creation. View cameras originally used sensitized glass plates, but today the standard is 4x5-inch sheet film. The small-format slr was originally designed around 35-mm roll-film. Both systems have been adapted for digital capture and both offer a range of technical choices; what these choices are and how they facilitate the photography of buildings deserves some study.