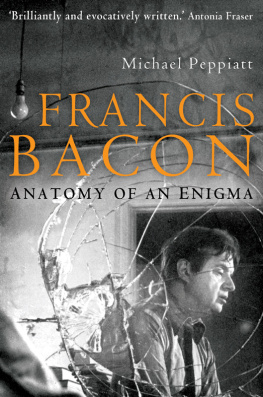

title: Francis Bacon : The Temper of a Man

author: >Bowen, Catherine Drinker.

publisher:Fordham University Press

isbn10: 0823215385

print isbn13: 9780823215386

ebook isbn13: 9780585125367

subject: Bacon, Francis,--1561-1626,Philosophers--Great Britain-- Biography, Statesmen--Great Britain--Biography, Lawyers-- Great Britain--Biography.

publication date: 1993

lcc: >B1197.B6 1993eb

ddc: 192

subject:

Bacon, Francis,--1561-1626, Philosophers--Great Britain-

Biography, Statesmen--Great Britain--Biography, Lawyers-

Great Britain--Biography.

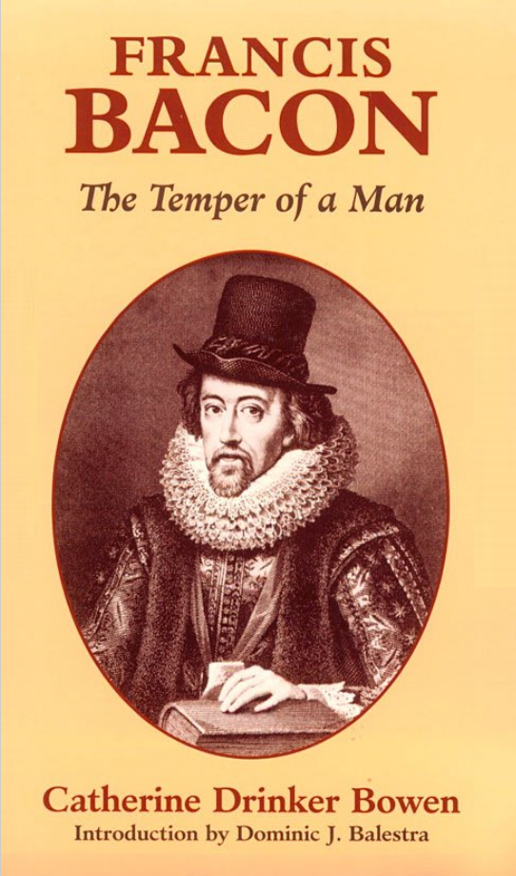

National Portrait Gallery

Sir Francis Bacon, Lord Chancelor of England by John Vanderbank

Francis Bacon

The Temper of a Man

Catherine Drinker Bowen

Introduction by Dominic J. Balestra

Fordham University Press

New York 1993

Copyright 1963 by Catherine Drinker Bowen

Copyright renewed 1991 by Ezra Bowen

Introduction 1993 by Fordham University Press

All rights reserved.

LC 93-32785

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Bowen, Catherine Drinker, 1897-1973.

Francis Bacon: the temper of a man/by Catherine Drinker

Bowen; introduction by Dominic J. Balestra.2nd ed.

for John H. Powell

Authority and place demonstrate and try the tempers of men, by moving every passion and discovering every frailty.

Plutarch, Lives

CONTENTS

Introduction by Dominic J. Balestra

Prologue: Lord Bacon's Reputation

I An Elizabeth Eden, 1561-1579

II The Struggle to Rise, 1579-1613

1. Two Conflicting Ambitions

2. Bacon and Essex

3. Bacon Begins to Write

4. The Ambition of the Unde rstanding

5. The Ambition of the Will

III Bacon Ascending: A Time of Glory, 1613-1620

1. Lord Coke's Defeat

2. Lord Chancellor

IV Impeachment, 1621

V A Noble Five Years, 1621-1626

Index

Illustrations appear between pages 118 and 119.

INTRODUCTION

Dueling Ambitions

In the 1560s England saw the birth of two geniuses, William Shakespeare and Francis Bacon. One, the son of a leather tradesman of modest means, went to the local grammar school, and by chance and natural endowment realized his genius in the theater. The other, the son of learned and wealthy parents, went to Trinity College, Cambridge, and by birth and design realized his genius in Court, despite his slow rise through thirty-six years of public service and sudden fall in less than two years as Lord Chancellor. Francis Bacon played many roles in the English Renaissance. He was a courtier, an essayist, parliamentarian, jurist, historian, Lord Chancellor and, through it all, a philosopher. His achievement in each is more than impressive, and the constellation of accomplishments is truly stellar.

Throughout his life Bacon was hampered by recurring bouts of poor health. Yet his persevering determination to fulfill two lifelong commitments succeeded in earning him a permanent place both as philosopher and as public servant. In a famous letter 1 of 1592 to his uncle, William Cecil Burghley, who was Secretary of State and first minister to Elizabeth, Bacon, at the age of thirty-one, "confesses" his dual ambition: for the vita activa in service to the queen and to England, and for the vita contemplativa. "Lastly, I confess that I have as vast contemplative ends, as I have moderate civil ends: for I have taken all knowledge to be my province." When Bacon wrote to his uncle, he already had served eight years in Parliament. Reading Bacon's life and his writings strongly suggests that these competing ambitions did not conflict, except in the very practical order of time.

There is a nascent pragmatism in Bacon's epistemological stance. For him any legitimate theory must serve human practices. Further in the letter, after distinguishing these contemplative ends from the "verbose disputations" of abstract philosophies or the aimless results of "blind experiments," Bacon identifies his contemplative ends as knowledge useful for and in service to humanity: "I hope I should bring in industrious observations, grounded conclusions, and profitable inventions and discoveries; the best state of that province. This, whether it be curiosity, or vain glory, or nature, or (if one take it favorably) philanthropic, is so fixed in my mind as it cannot be removed."

At this juncture, five years before the publication of the first edition (1597) of his Essays and well before The Proficienceand Advancement of Learning (1605), we find Bacon implying that the only worthwhile and genuine theoretical knowledge is that which serves the realm of human action. This is the seed of a vision which was nurtured and protected in The Advancement of Learning, and further developed and supported in the Novum Organon (1620), and which blossomed fully in his New Atlantis. The last was written in 1624, but published in 1627, the year following Bacon's death, by his chaplain, William Rawley, who introduced the work, reporting: ''This fable my Lord devised to the end that he might exhibit therein a model or description of a college instituted for the interpreting of nature and the producing of great and marvelous works for the benefit of men, under the name of Salomen's House, or the College of the Six Days Works.'' 2

Bacon's prophetic vision in his New Atlantis follows upon his theme of useful knowledge to outline an imaginative anticipation of today's research university, with its supporting network of various scientific and professional associations.

In addition to signaling that knowledge is a power to control the kingdom of nature in service to the kingdom of man, the letter to Burghley alerts us to a much more subtle aspect of Bacon's Essays. In providing some of Bacon's most perceptive analyses of and insights into the human condition, the Essays fill in the gaps in the study of human nature noted in Book II of The Advancement of Learning. 3 Consider, for instance, the question of what Bacon means by

"philanthropic" in the letter, then turn to the essay "Of Goodness and Goodness of Nature" for an essential element in his answer. Feigning any self-seeking advantage, he says directly "I take Goodness in this sense, the affecting of the weal of men, which is what the Grecians call Philanthropic. "4

Bacon continued to serve in Parliament for another twenty-six years, while taking on a succession of additional roles: as jurist, as minor counsel to Queen Elizabeth, as King's Counsel to James I (in 1604), then Solicitor-General (1607), Attorney-General (1613), later (1617) Lord Keeper like his father, and finally (in 1618) Lord Chancellor of England.

Bacon paid a high price for sustaining the vita activa on so many fronts.

Perhaps Bacon played too many roles. His dueling ambitions seemed to generate an ambivalence that may have worked toward his downfall. Achievement in so many corridors fueled the resentment of his enemies during his life; after his death it inevitably invited a maze of divergent opinion about this genius of the English Renaissance. There is a history of disputed judgments by biographers, historians, literary critics, and philosophers. On the one side, he has been hailed as a maker of modernity in multiple ways: as a founding contributor to a new, experimental scientific method, a new philosophical standpoint; as a maker of a new literary genre, the modern essay; and as a modern historian. On the other, he has been belittled as unoriginal in his scientific thinking and condemned as a hypocritical public servant whose impeachment as Lord Chancellor in 1621 betrays the author of the

Next page