P. D. Smith

DOOMSDAY MEN

The Real Dr Strangelove and the Dream of the Superweapon

For Bernard Smith (19252005)

I call on all scientists in all countries to cease and desist from work creating, developing, improving and manufacturing further nuclear weapons and, for that matter, other weapons of potential mass destruction such as chemical and biological weapons.

Hans Bethe, 1995

Peace is the only battle worth waging.

Albert Camus, 8 August 1945

This book has grown out of more than ten years of research and writing on the relationship between science and literature. The so-called two cultures are actually more closely connected than is commonly believed, and, as I hope Doomsday Men shows, tracing those points where they meet and cross-fertilize can reveal fascinating insights into our shared history.

I am immensely grateful to the Department of Science and Technology Studies at University College London for asking me to teach an occasional course on science and literature and for making me an Honorary Research Fellow. I was also pleased to have the opportunity to present work-in-progress on Doomsday Men to a research seminar in the department in 2005 organised by Jane Gregory. The feedback from this and from students on my courses in the previous two years helped to shape my thinking as the project developed. Many thanks also to Martin Swales, Emeritus Professor of German at UCL, for sharing over the years his insights into literature and for inviting me to speak to the English Goethe Society on Faust, Physicists and the Atomic Bomb in 2006.

Being affiliated to an academic department has also allowed me to make full use of the excellent libraries at UCL, Imperial College and the University of Londons Senate House. Librarians are the unsung heroes of non-fiction writing, and the staff at all these libraries were unfailingly helpful beyond the call of duty. Senate House overlooks Russell Square, where Leo Szilard stayed in 1933 and near where he had his Eureka! moment. I often thought of Szilards association with this area as I walked through the square to the library in the morning.

Special thanks go to Jon Turney for commissioning Doomsday Men and for believing in the book throughout its period of gestation. Not only were our working lunches immensely enjoyable, but his judicious editing of the initial typescript has contributed greatly to the finished work. Many thanks also to Will Goodlad, who inherited the book at Penguin, for his enthusiasm and commitment as well as for his admirably flexible interpretation of deadlines. Thanks are due as well to John Woodruff, whose knowledge of both science and science fiction made him the ideal copy-editor for the book. Any errors that remain are, of course, entirely my own responsibility. I am also grateful to my literary agents James Gill and Zoe Pagnamenta for placing Doomsday Men with such excellent publishers in the UK and abroad.

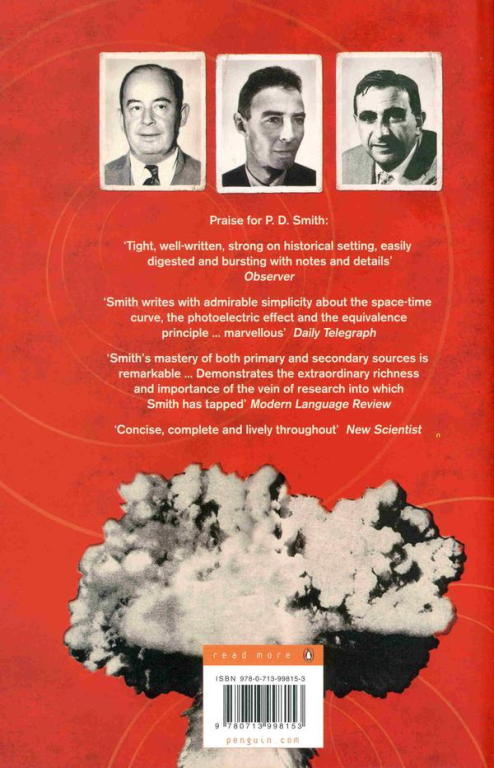

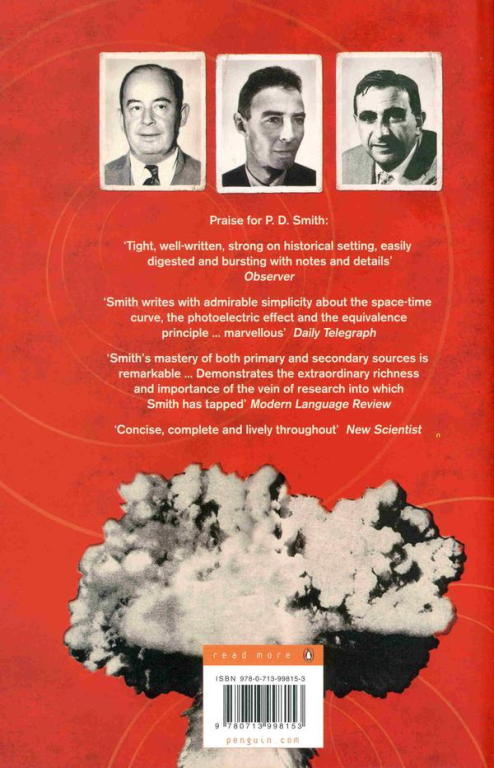

Writing a study as broad in its scope as this inevitably makes one indebted to the work of many scholars. I have tried to acknowledge their contributions in both the endnotes and the bibliography, but thanks in particular to Professor Paul Brians, Professor H. Bruce Franklin, Roslynn D. Haynes, William Lanouette and Richard Rhodes, whose books I have referred to while writing Doomsday Men. Many people have offered help and advice during the three years of research and writing. In particular, I would like to thank Joanne Atkinson, Brian Balmer, Professor Paul Bishop, Rebecca Hurst, Manjit Kumar, Julian Loose and Peter Tallack. For help locating images used in the book I would also like to thank Andrey Bobrov (ITARTASS), Heather Lindsay (Emilio Segr Visual Archives) and Felicity Pors (Niels Bohr Archive).

My father died while I was writing this book. I will never forget our conversations about books, writers and the life of the mind. The best of these typically began while we were walking across the South Downs and ended in a Sussex pub. This book is dedicated to him, although he never lived to see it finished. In the course of writing Doomsday Men I became aware of how the story of superweapons had touched previous generations of my own family. I am grateful to Major (Retd) R. G. Woodfield, MBE, Regimental Archivist of the Grenadier Guards, for providing information about my grandfathers military service.

Last but by no means least, I want to thank my partner, Susan, for reading the manuscript with a forensic eye for detail and for stoically putting up with my obsession with science, superweapons and other strangeloves during the last few years.

All other things, to their destruction draw,

Only our love hath no decay.

John Donne, The Anniversary P. D. SmithHampshire, January 2007http: //www.peterdsmith.com

For much of the period with which this book is concerned, many of the scientists and writers in my narrative were content to think in terms of inches, feet and miles, and pounds and tons. To retain this historical dimension, I have therefore chosen not to convert measurements to metric units.

Prologue

The Beginning or The End?

And he gathered them together into a place called in the Hebrew tongue Armageddon.

And the seventh angel poured out his vial into the air; and there came a great voice out of the temple of heaven, from the throne, saying, It is done.

Revelation 16: 1617

Homo sapiens is the only species that knows it will die. The thought obsesses us. From the earliest marks made on cave walls to our most sublime works of art, the fear of death haunts our every creation. And in the middle of the twentieth century, human beings became the first species to reach that pinnacle of evolution the point at which it could engineer its own extinction.

In February 1950, as the temperature of the cold war approached absolute zero, an atomic scientist conceived the ultimate nuclear weapon: a vast explosive device that would cast a deadly pall of fallout over the planet. Carried on the wind, the lethal radioactive dust would eventually reach all four corners of the world. It would mean the end of life on earth.

The world first heard about the doomsday device on Americas most popular radio discussion programme, the University of Chicago Round Table. Four scientists who had been involved in building the atomic bomb discussed the next generation of nuclear weapons: the hydrogen bomb.

During the programme, one of the founding fathers of the atomic age, Leo Szilard, stated that it would be very easy to rig an H-bomb to produce very dangerous radioactivity. All you had to do, said Szilard, was surround the bomb with a chemical element such as cobalt that absorbs radiation. When it exploded, the bomb would spew radioactive dust into the air like an artificial volcano. Slowly and silently, this invisible killer would fall to the surface. Everyone would be killed, he said.1 The fallout from his chilling suggestion spread fear around the world. For many it seemed as though the biblical story of Armageddon was about to be realized; the seventh angel would empty his vial into the atmosphere, and it would contain radioactive cobalt-60.

Those fears intensified when, in 1954, the United States detonated its biggest ever hydrogen bomb, scattering fallout over thousands of square miles of the Pacific. Such a bomb had been at the core of Leo Szilards idea. Newspaper headlines around the world proclaimed the imminent construction of the cobalt bomb. In fiction and films, Szilards deadly brainchild soon became the ultimate symbol of the threat humankind now posed to the very existence of our living, breathing planet.