Contents

PRINCIPLES

OF

FORENSIC MEDICINE.

T HE State avails itself of the knowledge, experience, and skill of the medical man for three distinct purposes:1. For the care of soldiers and sailors, prisoners, paupers, lunatics, and others for whose safety it makes itself responsible; 2. As officers of health and analysts; and 3. As skilled witnesses in courts of law.

The duties of the medical man in the first of these capacities are such as devolve upon him in the ordinary practice of his profession; but he is expected to prevent as well as to cure disease, and to add to professional skill administrative ability.

As medical officers of health, however, and as witnesses in courts of law, medical men have duties to perform for which the ordinary practice of their profession affords no adequate preparation; medical education, till of late years, no proper training; and medical literature no sufficient guidance.

The distinctness, importance, and difficulty of these duties led at length to the establishment of a distinct science, taught in separate courses of lectures, treated in separate works, and engaging the attention of men more or less separated and set apart for the practice of the corresponding art.

This new science either embraced all the duties the medical man may be required to perform on behalf of the State, in which case it received the name of Political or State Medicine; or it was divided into two sciences, the one known as Hygiene or Public Health, the other as Forensic Medicine, Juridical Medicine, Legal Medicine, or Medical Jurisprudence.

As regards the second of these, the term Forensic Medicine expresses with sufficient clearness the application of medical knowledge to legal purposes, and consequently it is used in the title of this work. The term medico-legal is also in common use, as in the phrases medico-legal knowledge, medico-legal experience, medico-legal skill.

It is to be regretted that this division of State Medicine has not made the same progress in this country as that of Hygiene or Public Health, a fact doubtless due to the difficulty of obtaining practical experience by those who are teachers of the subject.

In reference to the first of these sciences, Hygiene or Public Health, it is no part of our present duty to deal, but be it noted that in this department of State Medicine a registrable qualification is now obtainable only after compliance with a strict curriculum of study, and the possession of such qualification is necessary for all the more important Public Health appointments.

The history of Forensic Medicine is that of most other sciences. Necessity or convenience gives birth to an art practised by persons more or less skilful, without guidance from general principles; but its importance, and the responsibility attached to the practice of it, soon create a demand for instruction, oral and written, which gradually assumes a systematic form. Thus it was that the Science of Medicine sprang from an empirical art of healing. In like manner, the Science of Forensic Medicine took its rise in the necessity of bringing medical knowledge to bear on legal inquiries relating to injuries or loss of life; the medical witness being at first without guidance in the performance of his duty, and so continuing till a growing sense of the important bearing of his work on the interests of society, and on his own reputation, created a demand for instruction that could not fail of being supplied. Cases were accordingly collected, arranged, and commented on, illustrative facts sought after, special experiments devised and performed, till at length the medical witness received in books and lectures the same distinct instruction as the physician or surgeon at the bedside had already derived from written or oral teaching in the theory and practice of medicine, or of surgery.

But the importance of medical testimony received an earlier recognition from Continental Governments than from the public or the medical profession; for the first State recognition (1507) anticipated by nearly a century the first medico-legal treatise

The history of Forensic Medicine in England is of more recent date. It begins with the publication, in 1788, of Dr. Samuel Farrs Elements of Medical Jurisprudence, and the subject was first taught in lectures at Edinburgh, in 1801, by Dr. Duncan. sen., the first professorship being conferred by Government on his son in the University of that city in 1803. In England the first professorship was created in Kings College, London, Sir Thomas Watson being appointed to the chair in 1831. The new science soon justified the distinction thus conferred upon it, and made good its claims to more general recognition. It is now taught in all our medical schools, and recognised by the examining bodies; its principles are being constantly applied in our courts of law; and England continues to contribute her fair share of observation and research towards its extension and improvement.

The application of the principles of the sciencein other words, the practice of it as an artdevolves, for the most part, on the medical practitioner. But those specially versed in the entire subject, or in important parts of it (such as Toxicology), or eminent in certain branches of practice (such as midwifery and the treatment of the insane), are occasionally summoned to give evidence.

There are many reasons why the medical man should approach this class of duties with apprehension. He is conscious of the importance that attaches to his evidence; he is wanting in the confidence which a more frequent appearance as a witness would impart; he is painfully alive to the unstable foundation on which many medical opinions rest; he knows that it is not easy in practice to observe the rules of evidence with which in theory he may have made himself acquainted; and, above all, he shrinks from the publicity attendant on legal proceedings, the unreasonable licence allowed to counsel, and the disparaging comments of the Bench itself.

Sympathising in these reasonable apprehensions, some writers of eminence, and most authors on Forensic Medicine, have tried to prepare the medical witness for his duties by setting forth in more or less detail the precautions he should observe both prior to and during his attendance in court; and by special directions for conducting medico-legal inquiries under the heads of Post-mortem inspection, General evidence of poisoning, Unsoundness of mind, etc.; the general precautions to be observed in the witness-box being made the subject of distinct treatment under the title Medical Evidence.

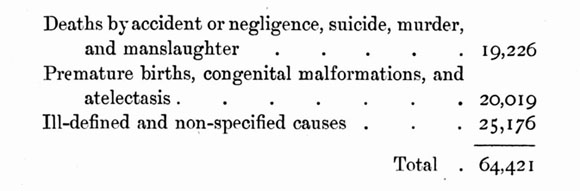

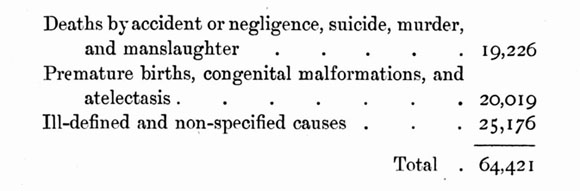

Before treating of the duties of the medical witness, it may be well to show the number of cases that occur year by year in England and Wales of a class to give rise to medico-legal inquiries. The following figures are extracted from the Annual Report of the Registrar-General for the year 1892:

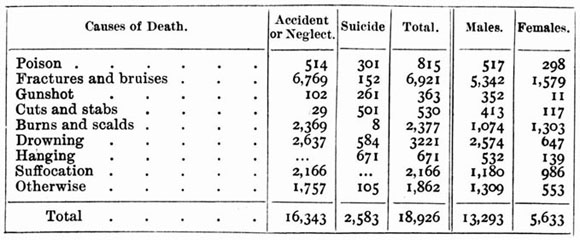

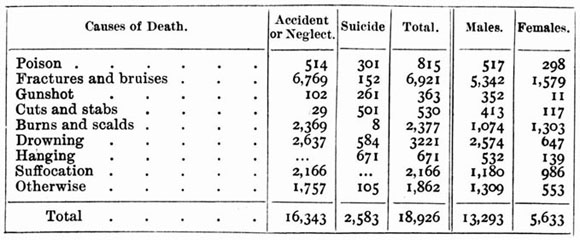

The following special causes of death were recorded in the year 1892:

In the same year (1892), the deaths by accident or negligence were distributed between the sexes as follows:Poison, men 340, women 174; Gunshot, men 95, women 7; Cuts and stabs, men 20, women 9; Drowning, men 2231, women 406; otherwise, men 1222, women 535.

The suicides were distributed as follows:Poison, men 177, women 124; Gunshot, men 257, women 4; Cuts and stabs, men 393, women 108; Drowning, men 343, women 241; Hanging, men 532, women 139; otherwise, men 87, women 18.