Robert Gellately

STALINS CURSE

Battling for Communism in War and Cold War

Abbreviations and Glossary

Bolsheviks: Majority faction of the RSDLP, founded in 1903

Central Committee: Soviet Communist Party supreme body, elected at party congresses

Cheka (or Vecheka): Chrezvychainaia Kommissiia (Extraordinary Commission), the original Soviet secret police, 191722; members of the secret police continued to be called Chekists even after 1922

Cominform: Communist Information Bureau, founded in 1947 as the successor to the Comintern

Comintern: Communist International organization, founded in 1919

GPUOGPU: Gosudarstvennoe Politicheskoe Upravlenie (State Political Administration)Obedinennoe Gosudarstvennoe Politicheskoe Upravlenie (Joint State Political Administration), the secret police, 192234

General Secretary: Stalins title as head of the Soviet Communist Partys Central Committee, in fact, as head of government and leader of the country

Gulag: Glavnoe Upravlenie Lagerei (main camp administration), eventually in charge of Soviet concentration camps

Kremlin: A fortified series of buildings in Moscow; also, the official residence of the Soviet head of government; also, the Soviet government

kulaks: Rich peasants

lishentsy: Soviet people without rights

NEP: New Economic Policy (192129), introduced by Lenin

NKVD: Narodnyi Komissariat Vnutrennikh Del (Peoples Commissariat for Internal Affairs), the secret police; in 1934, the OGPU was reorganized into the NKVD and named GUBG NKVD

Politburo: Main committee of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party

Pravda: Main newspaper of the Bolsheviks; later the semiofficial paper of the Soviet Communist Party

Sovnarkom/SNK: Council of Peoples Commissars, the government body established by the Russian Revolution; succeeded in 1946 by Council of Ministers

Soviet: Russian word for council

Stavka: Main command of the Soviet armed forces

TASS: Telegraph Agency of the Soviet Union, the official news distributor

Vozhd: Leader, equivalent to German Fhrer

Wehrmacht: German armed forces

Click to see a larger image.Click to see a larger image.Click to see a larger image.

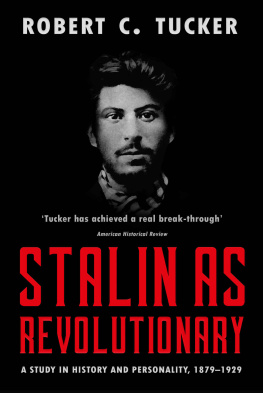

No one would have guessed it from the mug shots of one of the suspects picked up by the Russian secret police at the turn of the twentieth century. The bearded young man looked scruffy and slightly roguish, but his face revealed no obvious signs of deep-seated evil, or even anger and resentment. The police knew him as Joseph Vissarionovich Dzhughashvili, a troublemaker, labor activist, and renegade Marxist, and they had arrested him several times and exiled him to the East. From there he would escape and return to the fray in his native Georgia, in the Caucasus. He was a member of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party, and he had attracted the attention of Vladimir Lenin, leader of its Bolshevik faction. In 1912 the young firebrand adopted the nom de guerre Stalin, meaning Man of Steel. He won recognition in the political struggles of the day and especially for several writings, notably on the explosive and important nationality issue in the Russian Empire.

In late 1913 the police picked him up yet again, decided they had seen more than enough, and sent him to deepest Siberia. There he would remain until early 1917, when the entire structure of the tsarist regime came tumbling downthough not because of anything that Lenin and his tiny band of followers had done. Like Stalin, most of the key Bolsheviks were in exile as well.

The inexorable revolutionary energy in 1917 was generated by the Great War. Although in the beginning many regarded the war as a noble and patriotic affair for Imperial Russia, the years of endless deaths and sacrifice, coupled with discontent on the home front, did what several generations of dedicated rebels had been unable to do. The backlash against the war opened the floodgates of an elemental social revolution that swept away Tsar Nicholas II in February 1917 and made it possible for the Bolsheviks to return to what Lenin called the freest country in the world. When the Provisional Government continued the war, with no more success than the tsar, the revolution struck yet again in October, this time with Lenin leading the way. Fittingly enough, Stalin became the commissar of nationalities in the new government, an important post in the multinational empire of the day.

The man who would head the Kremlin for some three decades was born in Gori, Georgia, on December 6, 1878, though he routinely gave his birth date as December 21, 1879. He may have changed the date to avoid the draft at one point, but he was always secretive about his background. Indeed, the official biography he inspired, published in millions of copies before and after the Second World War, devotes little more than a dozen lines to his family and upbringing.

When Lenin became ill in 1921 and the next year was forced to spend time away from Moscow, infighting began among the party elite to determine the successor to the beloved leader. Stalin was well placed in the committees and won supporters because of his deep commitment to Leninism, his passion for the Communist ideal, combined with realism, and a ruthlessness in politics that Machiavelli would have appreciated.

Where had he found the mission to which he devoted his life and that dominated everything? Only a week after his hero died in 1924, in a speech to the Kremlins military school, Stalin attributed his boundless faith in Communism to Lenin. He pointed to Lenins Letter to a Comrade, a short pamphlet written in 1902. He had received it in the mail the following year, as he lingered in one of his exiles in the East, before he entered Lenins life. Although he told his audience in 1924 that the pamphlet had included a personal letter from its author, there had been no such message. Perhaps at the time, or on later reflection, Stalin meant that in a strange and compelling way, he felt as though Lenins Letter to a Comrade had been written just for him. That was the moment of his epiphany, when he found a new faith, and looking back he recalled that the pamphlet had made an indelible impression upon me, one that has never left me.1

Lenins short letter reads like the outline for a modern terrorist organization, together with a sketch for a new kind of state to follow. The vision was beyond anything seen before in socialist literature. At the head of the organization, there would be a special and very small executive group, the avant-garde leading the way to the future. Later in the Soviet Union this vanguard would be called the political bureau (or Politburo). It would include Lenin and quite remarkably also Stalin. Below the executive group, envisioned in the pamphlet, there would be a central committee of the most talented and experienced professional revolutionaries. Local branches would spread propaganda and establish networks, and in a preview of the future, there would be strong centralized control.

If Leninism provided the faith and the big idea, when did Stalin cross the psychological threshold of being willing to kill for it? Soon after May 1899, when he was expelled from high school, in fact a seminary, he became involved in labor politics in Georgias capital, Tiflis, and in its second city, Batumi. He was entering a violent world, particularly after a great railway strike in August 1900. The police frequently shot at strikers and tried to infiltrate the ranks. Workers responded with savage reprisals, including maiming and murdering the staff of certain companies. Stalins complicity in a first killing has been traced to 1902. However, here, as in several subsequent cases from the pre-1914 period, we have no direct evidence.2 The party in the Caucasus condemned anarchism and wanton terrorism, yet it certainly did not shirk from getting rid of police spies.3