Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

There are two extreme views about punctuation.

the first is that you dont actually need it because its perfectly possible to write down what you want to say without any punctuation marks or capital letters and people can still read it youdontevenneedspacesbetweenwordsreally they dont exist when we speak to each other after all and yet we nonetheless or should it be none the less understand what people are saying

The second is that its essential because it aids legibility. Its much easier to read if theres punctuation. Also, the marks show us how to read aloud in a way that reflects the pauses, rhythm, and melody that we use in speech. They help us see the grammar of complex sentences. And they help us sort out ambiguities otherwise nobody would ever have got the joke in Eats (,) Shoots & Leaves.

but that joke was funny precisely because its so unusual we dont encounter that sort of ambiguity most of the time when we write and its crazy to have to learn a complicated system that nobody agrees about just so that we can sort out rare cases of ambiguity

But punctuation isnt only about ambiguity and intelligibility. It also shows our identity as educated people. For historical reasons, society expects people to spell correctly and to punctuate correctly.

how can anything be correct if theres so much disagreement about it theres an example already in what youve written you put a comma in after the word rhythm in your first comment thats something a lot of people including some ministers of education would disapprove of

There are historical reasons for that, too.

what are these historical reasons you keep going on about

Read on

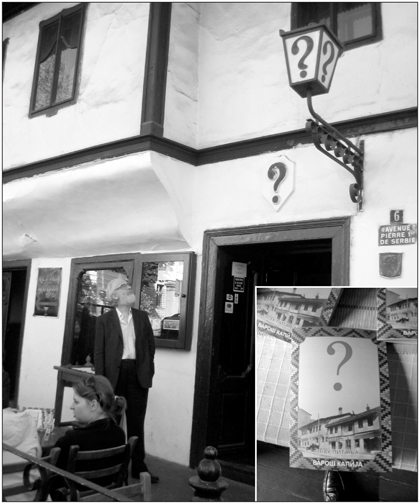

If you walk along the main shopping street in Belgrade, in the direction of Kalemegdan Park, and turn left just before you reach the end, you will find yourself in Kralja Petra street. Towards the bottom, opposite the Serbian Orthodox cathedral, is the oldest traditional kafana, or tavern, in the city. And its name is a punctuation mark.

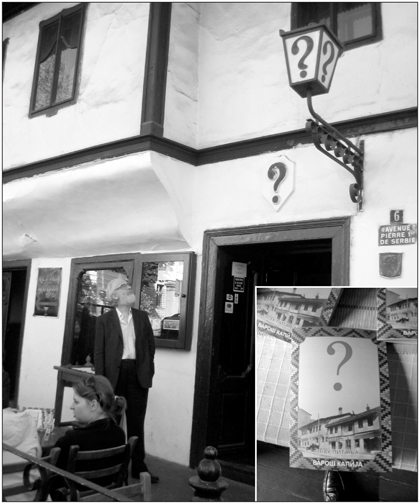

A question mark, to be precise. And that is how everyone knows it. People say they will meet at the question-mark tavern znak pitanja in Serbian. You cant miss it, as on the outside wall is a prominent lantern with a large question mark on it. And inside you are surrounded by menu question marks. It is a typographical paradise. If there were a Question-Mark Protection Society, this is a place where its members would surely wish to end their days.

Behind every punctuation mark lies a thousand stories, and nowhere is a story more interesting than in the case of number 6 Kralja Petra. In 1892, the owner wanted a new name for his tavern and looked for the nearest landmark, which was the church across the street. So he called it By the Saborna Church. But he hadnt taken into account the likely reaction of the Church authorities, who were furious at the thought of the name of their cathedral being associated with a pub. Temporarily at a loss for an alternative, he put a question mark on the door. And it stayed.

A question mark as the name of a pub. Its a function of punctuation that would never have been dreamed of by those who first thought of adding marks to their writing to make it easier to read. But the story of English punctuation is littered with such personal preferences, unusual practices, and arbitrary decisions as well as occasional linguistic reasoning. For such a tiny system only a dozen or so marks in common use, after all theres an amazing amount of uncertainty over usage.

The author admires the question-mark tavern. (inset) The tavern menu cover.

And an even more amazing amount of personal involvement. What other area of language has generated motivation of the kind shown by the two enthusiasts who went hunting for punctuational errors all the way across America, correction-pens in hand, risking jail in the process? What other area of language has produced as specific an organization as the Apostrophe Protection Society? What other account of a language topic has achieved anywhere near the remarkable 3-million-plus sales of Lynne Trusss punctuation manifesto, Eats, Shoots & Leaves?

When a language is written down for the first time, the writer has to perform two apparently simple tasks: spell the words, and punctuate the sentences. Both turn out to be unexpectedly complicated. Ive told the story of how writers solved the spelling task in Spell It Out. This book tells the story of how they solved the second or rather, didnt entirely solve it, judging by the furious rows over what counts as correct punctuation which still surface in the media. One only has to write potatos to elicit an emotional reaction of biblical proportions.

There is something really special about punctuation, and its story needs to be told. Who were the people who introduced punctuation to the English language? Why did they do it? How did their invention evolve over the centuries? When did the enthusiasms and uncertainties originate? What is happening to punctuation today? And what is its future? That is what this book is about.

Up on the second floor in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, in a gallery displaying artefacts from early England, there is a beautiful teardrop-shaped object. A decorated golden frame surrounds a colourful enamelled design protected by a flat panel of polished rock crystal. It shows the picture of a man dressed in a green tunic, and holding a flowered sceptre in each hand, his wide eyes gazing intently at something we do not see. And around the rim of the object, just a few millimetres thick, is an Old English inscription in Roman letters:

AELFREDMECHEHTGEWYRCAN

There are no spaces between the words. Inserting these, we get

AELFRED MEC HEHT GEWYRCAN

Alfred me ordered to make

= Alfred ordered me to be made

This is King Alfred the Great, and the object has come to be called the Alfred Jewel.

It was found near Athelney Abbey in Somerset in 1693, the place where Alfred launched his successful counter-attack against the Danes in 878. There has been much debate about the identity of the man, and what the purpose of the jewel was. An important clue is the base of the object, which is in the form of a dragon-like head with a cylindrical socket in its mouth. What did that socket hold? Probably a pointer, used to help a reader to follow the lines of text in a manuscript, which would often be placed on a stand some distance away from the reader. Its now thought the large-eyed figure represents the sense of sight. His eyes are wide open and focused because he is reading.

The Alfred Jewel in outline, showing (left) the location of the inscription on the object, and (right) the way the inscription surrounds the figure.

For people interested in English punctuation, the jewel inscription provides an important opening insight. There isnt any. This is a sentence, but theres no full stop. All the letters are the same, capitals, so theres no contrast showing where the sentence begins or that Alfred is a name. And the inscription lacks what to modern eyes is the most basic orthographic device to aid reading: spaces to separate the words.