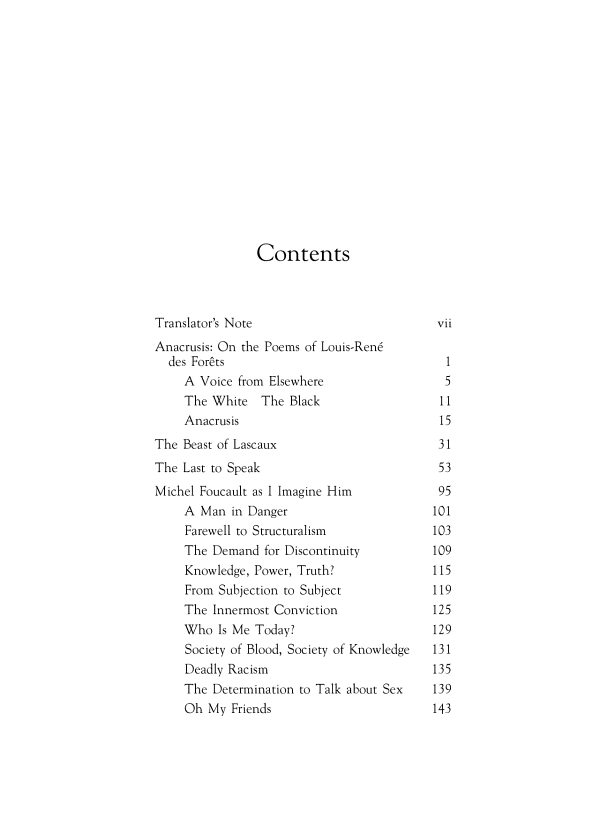

Translators Note

I would like to thank Monique Antelme, lifelong friend of Maurice Blanchot, for her kind words of encouragement. I would also like to thank Christophe Bident for his ever-helpful biography of Blanchot, Maurice Blanchot: Partenaire invisible.

I am very grateful to Charles Shepherdson, editor of this series, both for his informed enthusiasm for Blanchots work, and for including this text in the series. I thank James Peltz, director of SUNY Press, for his help.

I am deeply indebted to Leslie Hill for sending me a copy of the 1986 Fata Morgana dition dfinitive of Le dernier parler (which I used as reference for the present translation) along with a copy of the earlier version of the same text that appeared in the 1972 Revue des belles lettres, and for his help in locating the original Celan texts.

I am grateful to Michael Naas for his thorough reading of this text in manuscript; his comments and suggestions were invaluable.

I am also grateful to ric Trudel for his thorough reading of my translation of Anacrouse, and for his generous commentary on the poems of Louis-Ren des Forts, whose work he has studied and enjoyed.

My husband, the poet Robert Kelly, was especially helpful in the Celan and Char chapters, and his careful reading and thoughtful revisions of the entire book were deeply appreciated.

I would also like to thank Kevin Hart, Marina van Zuylen, and Odile Chilton for their muchneeded support and advice.

A note about the Celan chapter: my translations of the Celan poems are only from Blanchots own French translations of the original textsnot from the German. Blanchots readings of the German into French are often quite free, both in meaning and in arrangement of the text.

Several texts in this book have been translated before: Leslie Hills The Beast of Lascaux appeared in the Oxford Literary Review, No. 22, 2000, pp. 918; The Last One to Speak, as translated by Joseph Simas, appeared in Translating Tradition: Paul Celan in France, a special double issue (#8/9) of ACTS: A Journal of New Writing, 1988, pp. 228239; Michel Foucault as I Imagine Him, as translated by Jeffrey Mehlman, was published in Foucault/Blanchot, New York: Zone Books, 1990, pp. 61109. Ostinato, by Louis-Ren des Forts, has been translated by Mary Ann Caws for University of Nebraska Press, 2002. I used all these translations as reference; my only reason for translating them anew is my firm belief that there can never be enough translations of a given text, especially one as subtle and full of nuance as a text by Blanchot. Just as every new book brings us a little closer to the Mallarman concept of the Ideal Book, so every translation brings us closer (we hope) to the original. Fortunately although the Ideal Translation may not exist, the Ideal Readeryou, reading thisdoes, and he or she likely has blue pencil in hand.

CHARLOTTE MANDELL

May the childs voice in him never be silenced, may it fall like a gift from the sky offering to dried-out words the brilliance of his laughter, the salt of his tears, his all powerful savagery.

Louis-Ren des Forts from Ostinato

A Voice from Elsewhere

When I was living in ze, in the little room (made bigger by two views, one opening onto Corsica, the other out past Cap Ferrat) where I most often stayed, there was (there still is), hanging on the wall, the likeness of the girl they called The Unknown Girl from the Seine, an adolescent with closed eyes, but alive with such a fine, blissful (but veiled) smile, that one might have thought she had drowned in an instant of extreme happiness. So unlike his own works, she had seduced Giacometti to such a point that he looked for a young woman who might have been willing to undergo anew the test of that felicity in death.

Anacrouse initially appeared under the title Une voix venue dailleurs, from ditions Ulysse, in 1992.

The poems by Louis-Ren des Forts to which Maurice Blanchots texts refer are collected in Les Mgres de la mer (Mercure de France) and Pomes de Samuel Wood (Fata Morgana). The White / The Black refers to extracts from Ostinato (Mercure de France; English edition: University of Nebraska Press, translated by Mary Ann Caws, 2002).

It is out of tact that I evoke this image, in order not to alter the haunting quality of the poems of Samuel WoodSamuel la Fortwhere there rises up in the night dream the childlike figure, sometimes smiling among the asters and roses, standing in the full light of her grace or holding up a candle that she blows out as if reluctantly so that she wont be seen disappearing. She makes herself seen only in dreams / Too beautiful to put the suffering to sleep and on the contrary aggravating it since she is there only in dreams, a presence about which we know at the same time that it is deceiving. Deceiving?

No, she is there, really there / What does it matter if sleep takes advantage of us.

It would be better to abandon prudent reason and destroy the daytime wisdom that seeks to destroy the wonderful apparition / Welcomed as one trembles at the sight of a face seized by death. She is there to watch over us / Who go to sleep only to see her.

Thus the dream and the rational day pursue an unceasing battle.

A dream, but is there anything more real than a dream? And how can one survive without dreaming That the child, drawn to her familiar places / Comes into this garden of roses, and every night / Returns to fill the bedroom with her candid flame / That she holds out to us like an offering and a prayer?

There is also that woman seated on a window ledge / And she is always the same. Who is she, then? What sign is she making with her fingers gloved in red? And if we tear ourselves from sleep to question her and lose her, here she is again, returning on the following nights in a similar posture, resting against another window.

A figure that disturbs me, since I have met her too, but during the day, diurnal and spectral. Messenger of Melancholy, so similar to the apparition evoked by Henry James in The Turn of the Screw, motionless like a woman conscious of her guilt, slightly turned away so that we can escape from the memory of our own guilt.

Figures that are too real to last.

And that is when the questioning that exposes the illusion intervenes: These visions were only an error of oblivion. It is forbidden to ignore the laws of nature and pretend to checkmate death. Samuel Wood or his double utters the judgment: Irreparable crack. Let us take note of it. / Now we are sorry as long as we live.

But then another temptation occurs: why not cut the moorings so as to go toward her in death, by a death that is not only consented to, but summoned, chosen like the perfect form of silence?

Or, in another realistic perspective, why not wait for the memory to weaken, ceasing to suffer by ceasing to see her / Joining us on nights favorable to encounters?