ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The editors wish to thank the following foi permission to reprint material included in this anthology:

Cambridge University PRESSfor selection from Second Characters, by the Earl of Shaftesbury, edited by Benjamin Rand.

COSMOPOLITAN SCIENCE AND ART SERVICE CO., INC., and THE EXECUTORS

Of The Estate Of Dr. Ludwig Schopp for selection from De Ordine, by St. Augustine, translated by Robert P. Russell. Encyclopedia BRiTANNicAfor "Aesthetics," by Benedetto Croce.

THE EXECUTORS OF THE ESTATE OF C. K. OGDEN and W. F. JACKSON

Knight for selection from De Musica, by St. Augustine, translated by W. F. Jackson Knight. Faber And Faber Ltd. for selection from The Enneads, by Plotinus, translated by Stephen MacKenna.

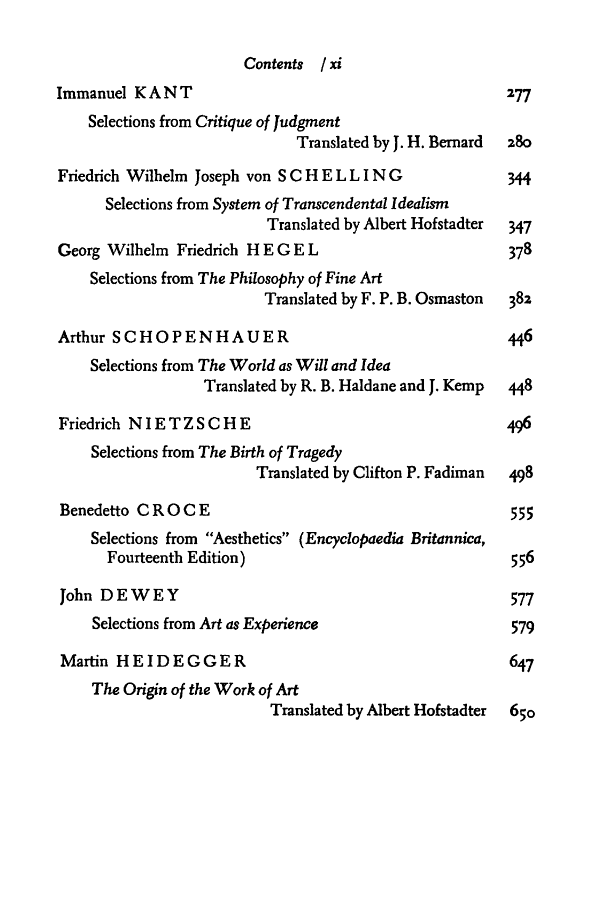

Harper & Row, Publishers, Inc. for Albert Hofstadter's translation of Martin Heidegger's "The Origin of the Work of Art," originally published in Heidegger's Poetry, Language, Thought, 1971 by Harper & Row.

c. p. Putnam's Sons For selection from Art as Experience, by John Dewey. Copyright, 1934, by John Dewey. Published by Minton, Balch & Co.

Random House, Inc. for selection from The Birth of Tragedy, by Friedrich Nietzsche, translated by Clifton P. Fadiman, in The Philosophy of Nietzsche. Copyright, 1927, and renewed, 1954, by Random House, Inc.

University Of Missouri Press for selection from Commentary on Plato's "Symposium," by Marsilio Ficino, translated by Sears Reynolds Jayne.

The Clarendon Press, Oxford for selections from Aristotle's Works, edited by W. D. Rossand for selections from The Works of Plato, translated by Benjamin Jowett.

PREFACE

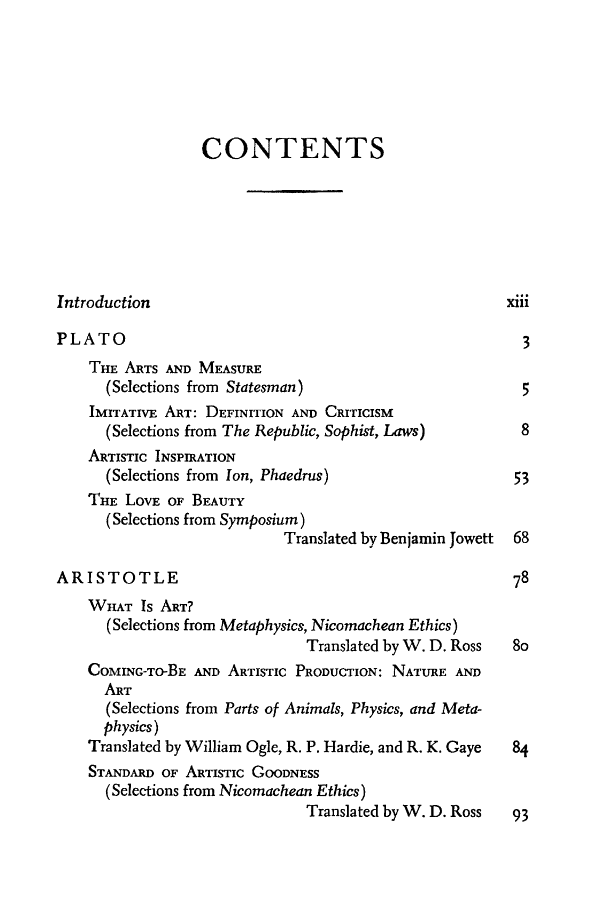

The philosophy of art constitutes one of the recurrent concerns of Western philosophy. Nevertheless, what a philosopher has to say about art, the way he uses art in his exploration of the human situation, the lessons he draws from art in learning about realityall this is often neglected for the more traditional topics of metaphysics and epistemology. In order to illustrate the relevance of art to philosophy, as well as of philosophy to art, we have brought together the writings of a number of philosophers. In every case we have let them speak at length, for philosophies of art cannot be stated briefly. They draw their strength not only from philosophical inquiry, but also from research into the arts themselves.

The demands of space made by each writer have limited the number that could be included. Yet we have, we believe, for all our selectiveness, included the best. Obviously some inclusions and exclusions are a function of our personal preferences and tastes; that is unavoidable. Because we have not tried to be chronologically complete or systematically thorough there are chronological gaps, such as that between Augustine and Ficino, and there are positions unrepresented, such as those of Thomas Aquinas, Marx, Freud, and Jung. The gaps occur because there are periods in Western thought in which the philosophy of art was of little interest to philosophers. The omission of certain positions is harder to justify, but we found as we examined the literature that there are some positions without able defenders. There are other positions which, to be represented, would have to be synthesized out of bits and fragments. We have taken it as a principle that where sustained argument could be found it was preferable to aphorisms and vague, incomplete statement. The psychological writings, though fruitful, do not present a truly philosophical position.

It may also seem surprising that no French philosopher is included. We considered Batteux, Boileau, Dubos, Diderot, Alain, Bergson, Sartre, and others. But in every case we concluded that what we found was not a philosophy of art, in the fullest sense, but either criticism, or theory of taste, or at most fragments of a philosophy. The philosophers we have chosen are thinkers who have taken the problems of art and beauty as central to the elaboration of their philosophies. Together they show us the power and insight of which philosophy of art is capable. We have tried to present them in as full a form as a collection of this kind permits. Though we have been forced to omit passages within all except one or two of the essays, the abridgments are in the service of clarity, and do not, we believe, exclude anything of importance for an understanding of the thought.

Our principle of selection, then, is simply greatness: these writings present the most profound and fruitful philosophies of art in the Western tradition.

INTRODUCTION

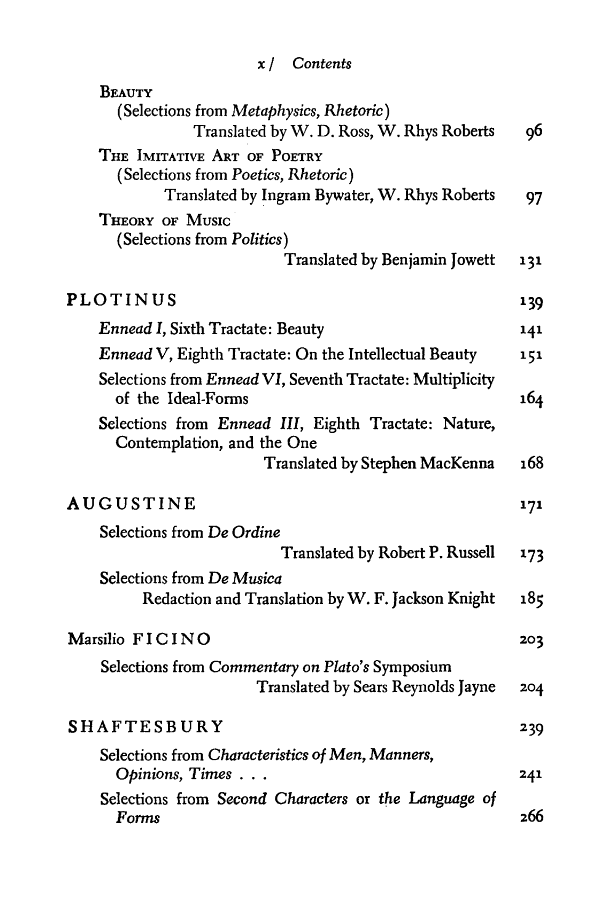

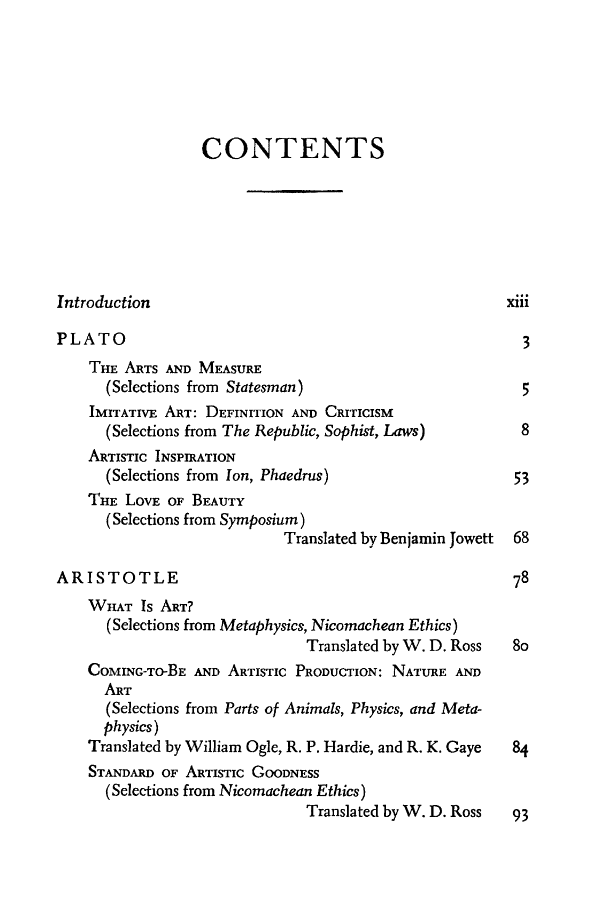

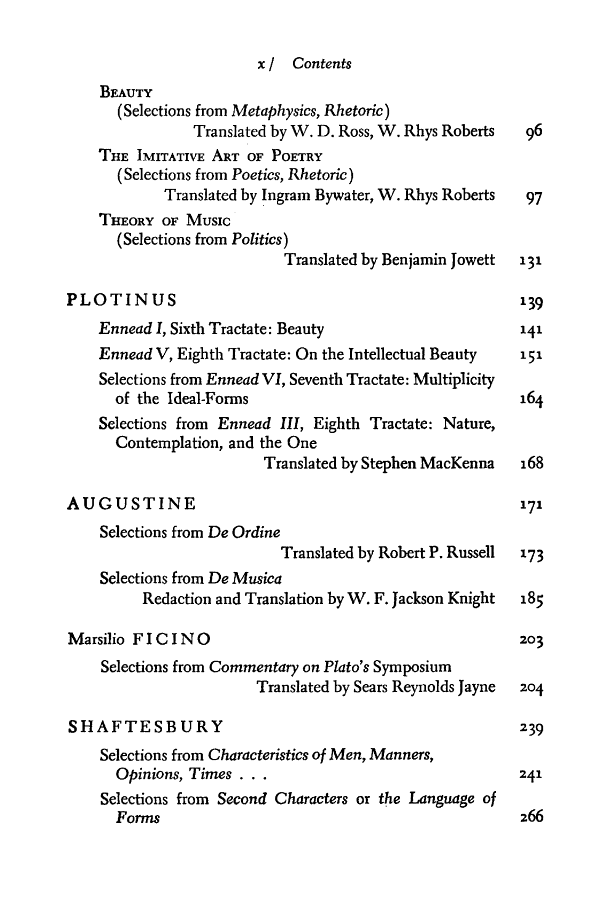

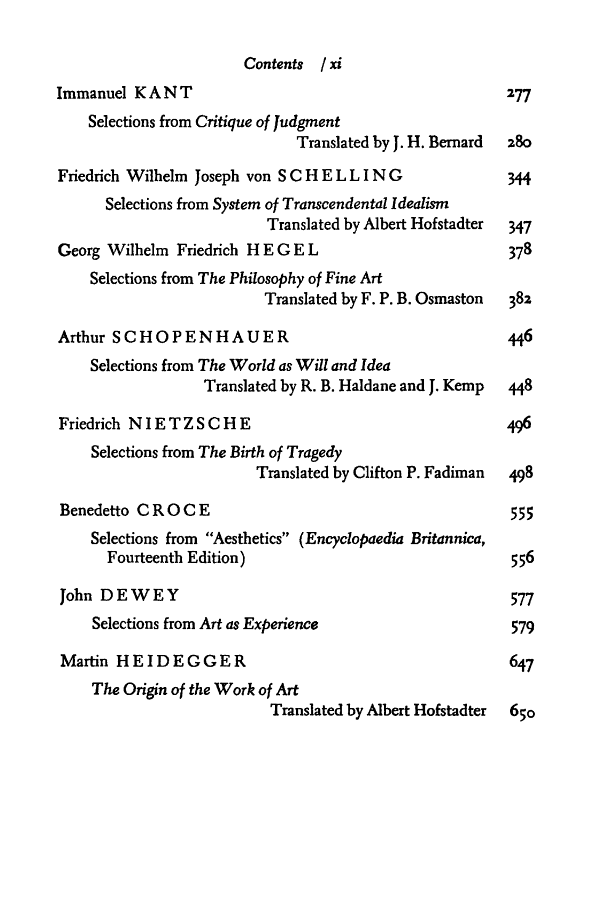

This anthology begins with Plato and concludes with Heidegger, a span of some 2,200 years. That it should begin with the most notorious inquiry into art of the classical world and end with a well-known contemporary existentialist would suggest that all of Western thought on art and beauty is included here. But it will be immediately evident, on consulting the table of contents, that the inclusions are few, and that the names, while mostly familiar, are but a small selection from a much larger company. While the philosophy of art and beauty is as old as philosophy and as new as the present, it has not always been a dominant philosophical interest. It comes to the forefront of philosophical thought, and then recedes, only to be brought forth once more as the leading theme. Through this collection we can see how it has been developed and transformed through the years, how it reflects the temper of an age and provides leading ideas for artists, critics, and the society that nurtures art. For philosophies of art and beauty are as various as the philosophies of human conduct, politics, science, history, and ultimate reality that have been the chief work of the human mind throughout our history.

Beyond our natural desire to understand the human activity of the making and enjoyment of art, there is a profound motive and primitive need behind philosophies of art. A powerful analogy immediately comes to men when they think about themselves and the universe they inhabit: the maker of the universe and the object he makes are like the human maker and his artifact. The order and harmony of the cosmos are like the beauty of art. Somehow man participates in the ordering of the universe in his power to make and to respond to art objects. Thus, early philosophies of art and beauty are intermixed with cosmological inquiries and it is only relatively late in the development of philosophy that the philosophy of art can be thought of as distinct from ontology and theology. The greatest philosophies of art, then, are part of broader inquiries into man and nature.

To a reader familiar with writings in aesthetics and the philosophy of art our selections may appear strangely overweighted in the direction of idealism and the high German metaphysics of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. There is good reason for this: our selections have to do with aesthetics as a branch of philosophy, not with criticism or the principles of criticism. In a philosophy of art, or in philosophical aesthetics, more generally speaking, beauty and art are understood in terms of essential philosophical ideas, while philosophy itself is taken to be at least in part constituted by aesthetic reflection. Thus the great philosophies of art have interpreted beauty and art in metaphysical terms as a natural expression of the belief that philosophy is born in the aspiration toward and understanding of the beautiful. As Croce has said, "from this character of aesthetics it follows that its history cannot be separated from that of philosophy at large, from which aesthetics receives light and guidance, and gives back light and guidance in its turn." However, not all philosophers and not all forms of philosophy give equal weight to aesthetics and the philosophy of art; hence the historically spotty and discontinuous character of the selections. For reasons that may become apparent, certain periods (for example, the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries) placed philosophy of art at the center of philosophical speculation.