MONSTERS

ALSO BY ED REGIS

Regenesis (with George M. Church)

What Is Life?

The Info Mesa

The Biology of Doom

Virus Ground Zero

Nano

Great Mambo Chicken and the Transhuman Condition

Who Got Einsteins Office?

Copyright 2015 by Ed Regis

Published by Basic Books,

A Member of the Perseus Books Group

All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. For information, address Basic Books, 250 West 57th Street, New York, NY 10107.

Books published by Basic Books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the United States by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 2300 Chestnut Street, Suite 200, Philadelphia, PA 19103, or call (800) 810-4145, ext. 5000, or e-mail special.markets@perseusbooks.com.

Designed by Trish Wilkinson

Set in 11.5 point Fairfield LT Std

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Regis, Edward, 1944

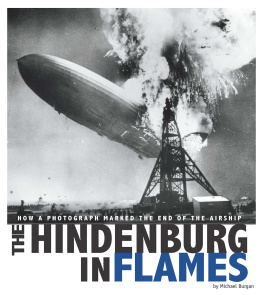

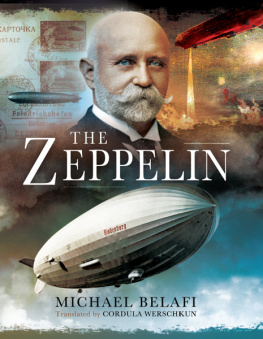

Monsters: the Hindenburg disaster and the birth of pathological technology / Ed Regis.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-465-06160-0 (e-book) 1. Hindenburg (Airship) 2. Aircraft accidents. 3. Technological innovationsSocial aspects. 4. TechnologyHistory. 5. TechnologyRisk assessment. I. Title.

TL659.H5R44 2015

303.48'30904dc23 | 2015022692 |

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

The Hindenburg over Manhattan, May 6, 1937, three hours before its destruction.

To Pam

CONTENTS

The destruction of the airship Hindenburg on May 6, 1937, at Lakehurst, New Jersey, was one of the most visually shocking events of the midtwentieth century: it was the first time that a large-scale disaster was recorded on film, then coupled to a live, first-person account of the unfolding drama, and the result presented to the masses on larger-than-life motion picture screens. The combined image and soundtrack describing a scene of wild furyuntamed, uncontrolled, and unstoppableinstantly became an iconic, defining symbol of the era.

But that cataclysm, overlaid with portents of doom, also represented something else that has hitherto been little noticed, although it was almost as obvious, and just as striking, in its own way. The Hindenburg was an example of superior engineering, an object of advanced technology. Despite those attributes, it became a smoldering wreck in a bit more than thirty seconds. That should not have come as a surprise to its builders or operators, or for that matter even to its passengers. For one thing, the physical makeup of the craft virtually foretold and predetermined its fate: the Hindenburg was an immense vessel filled with more than seven million cubic feet of hydrogen gas, a highly flammable, indeed explosive, substance. For another, the crafts fiery ending had been preceded by a number of prequels, many of them equally if not more spectacular, and some of them even more deadly, although none of them had been captured on film. In fact, prior to the Hindenburg disaster, a total of twenty-six hydrogen airships had been destroyed by fire due to accidental causes, sometimes killing every last person aboard. Yet hydrogen-inflated zeppelins continued to be built and routinely flown in commercial passenger service. How did it come about that so much time, money, and labor were spent designing, building, maintaining, and operating a craft that was continuously risking the lives of its passengers and constantly flirting with death?

And it was not only German zeppelins that ended their lives as blackened and charred metal husks. The British built and operated their own hydrogen-filled airships, some of which broke up in midair; one of them killed forty-four of its passengers, even more than were lost in the Hindenburg. In 1930 the immense R 101 set off from the Royal Airship Works at Cardington on its maiden long-distance flight, which was to India. Aboard was the British air minister, Lord Thomson, who had said of the craft: She is safe as a houseexcept for the millionth chance. Eight hours after takeoff the R 101 crashed into a hillside in France, where it exploded and burned, killing forty-eight of those aboard, including Lord Thomson.

Plainly, there was something deeply wrong with an oversize technological artifact that regularly put millions of cubic feet of explosive gas into close proximity with live and innocent human beings. The Hindenburg was a prototypical example of a pathological technology, one whose obvious and sizable risks were ignored, discounted, minimized, and swept under the rug by the influence of what amounted to an overriding, all-consuming, and almost irresistible emotional infatuation. That mental aberration produced a cognitive blindness to the crafts systemic defects. The Hindenburg and other zeppelins were built and flown because the bigger these leviathans got the more they acquired a spellbinding, mesmerizing, hypnotizing, practically immobilizing sway over human minds and emotionsnot only those of the public and paying passengers, but also of their designers, builders, and crew members.

Indeed, even after the Hindenburg disaster, which was the most hair-raising public calamity up to that point, the Germans did not abandon their cherished invention. Instead, the Zeppelin Transport Company (owners of the Hindenburg) inflated with explosive hydrogen a second airship of equal size, the Graf Zeppelin II, and sent it aloft on thirty flights, many of them under the command of Captain Albert Sammt, who himself had been burned and scarred for life in the Hindenburg inferno. This, too, was pathological. In fact, the Graf Zeppelin II was never freely and voluntarily abandoned by its operators; instead, it was scrapped in 1940 only because Reich air minister Hermann Goering had decided that the ships metal framework and components could be more fittingly used in bombers.

Next page