For Bridgit

Airship would not have sailed without her

A Conway Maritime book

John Swinfield, 2012

First published in Great Britain

in 2012 by Conway,

an imprint of Anova Books Company Limited,

10 Southcombe Street,

London W14 0RA

www.anovabooks.com

www.conwaypublishing.com

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright owner.

John Swinfield has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this work.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data:

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

First eBook publication 2012

eBook ISBN 9781844862092

Also available in hardback

Hardback ISBN 9781844861385

Anova Books Company Ltd is committed to respecting the intellectual property rights of others. We have made all reasonable efforts to ensure that the reproduction of all content on these pages is included with the full consent of the copyright owners. If you are aware of any unintentional omissions please contact the company directly so that any necessary corrections may be made for future editions. Full details of all the books can be found in the Bibliography.

Editing and design by David Gibbons

To receive regular email updates on forthcoming Conway titles, email with Conway Update in the subject field.

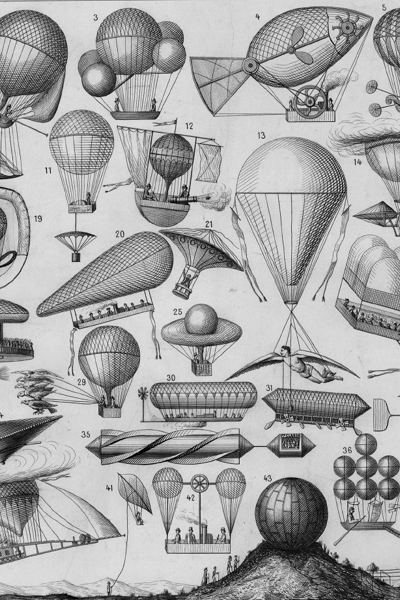

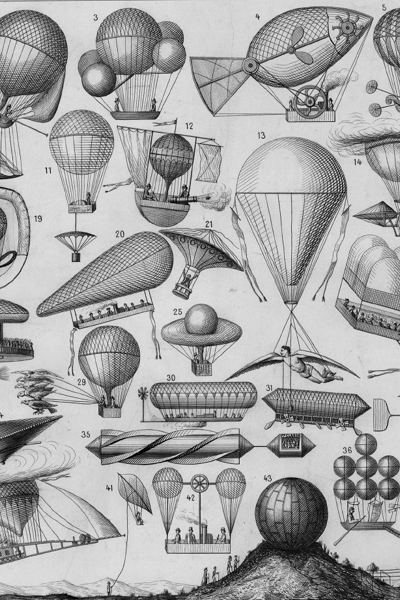

Front endpaper: It all began in 1783 with a hot-air balloon created by Joseph and Etienne Montgolfier, paper manufacturers in Annonay, some forty miles from Lyons, in Frances Rhone Valley. Wondrous and diverse were the machines that followed. (Library of Congress)

Rear endpaper: A colossal spiders web. The ambitious interior framework of a giant Barnes Wallis airship under construction c.1920s. (SSPL/Getty Images)

PROLOGUE

A t 7.25pm on 6 May 1937 the airship Hindenburg nosed cautiously towards the tip of her mooring mast in New Jersey, America. An ocean liner of the skies, her passage from Germany had been delayed by stormy weather and strong headwinds. Suddenly a billowing hydrogen fire erupted near her tail, devouring the ship with a terrible roar. In seconds her steel frame melted into a charred and twisted tangle. Passengers leapt from the promenade deck into the jaws of the inferno as the ship fell out of the sky, their screams drowned by the clamour and bellow of the conflagration. A reporter sobbed into his microphone and the world would recoil as the torment of the craft and the last moments of her passengers were flashed by newsreel around the globe.

Seven years before the calamity of the Hindenburg another wingless leviathan, the British airship R101, set sail for India on the most testing voyage any such vessel had undertaken. A seventh of a mile long, she floated upwards with a slow reluctance into the autumnal dusk of an early evening sky. Her five diesel engines throbbed, red and green navigation lights twinkled in the darkening heavens, white pin-pricks of light shone from torches waved by the crew in farewell to wives and children on the ground. Those aboard waved through the port-holes at the throng below. Before retiring to their bunks, tired from the excitements of the day, they watched the ground slide slowly away, the quickening gloom shrouding the ships vast silver envelope. In the saloon they had a grand supper with fine wines, toasting the ship and their voyage with balloons of cognac. The asbestos smoking-room grew rich with the perfumed haze of the finest Havanas, the cigar-lighter chained to a feather-light table. Inches above their heads more than five million cubic feet of hydrogen in huge bags kept the craft aloft. The crew used a narrow gangway running bow-to-stern in the envelope, monitoring gasbags, fuel tanks and ballast controls. The engines and those who tended them were in small and deafening cars fastened like limpets to the ships exterior; each engine drove a huge propeller. The fabric of its cover stretched for seven acres around a jigsaw of girders, a giant tent as gloomy and cavernous as a cathedral; inside was to be in the belly of a mammoth, dim yellow lamps casting pools of shadowy light. The girders groaned, the ship seemed alive. The wind had picked up, clawing at the fabric. The forecast warned of dangers ahead: a slow drizzle turning to rain, water streaming off the cover, making the ship heavier, urging her back towards the ground.

On the bridge in the control gondola the officers went about their business, warming the engines before opening them to full throttle, adjusting the angle of flight, keeping the nose up, spinning the ships wheel, getting the feel of her, rudder, elevator and ailerons. Her captain, Flight Lieutenant Herbert Carmichael Irwin, known as Bird to the ships company, was a tall, quiet, dignified Irishman. On his issuing of the naval command Prepare to Slip, his ship had been liberated from its shackle at the pinnacle of the tower. She had shivered and trembled, a silver-skinned colossus scenting freedom, uncertain if to stay or to run. Her nose gently dipped, as if pulled back to earth by unseen wires. Water gushed from her belly, thousands of gallons of ballast, helping her to climb higher into the leaden sky, lifting her bows. She was pregnant with weight and overloaded. There was far to go and much to do. It was the start of a spectacular adventure, the culmination of a five-year building programme fraught with politics and controversy. She was sailing to Ismailia, in Egypt, where she would host a glittering aerial dinner for the finest in the land; later she would top up her tanks of diesel and water before continuing her four-thousand-mile passage to India.

This book is an examination of the faltering and calamitous history of the airship, the friction over control and deployment and the protracted and fractious manner in which the military toyed with a commercial proposition while trying to bend it to its own ends. It tracks the dismal progress of a British Imperial airship ensnared in government committees, its evolution hampered by inter-service chicanery culminating in a degree of government control unimagined by its progenitors, and which led to the intervention of the Ramsay MacDonald government and construction of the airship R101. The era saw unprecedented administrative upheaval in the services, the troublesome birth of the RAF and frequent changes of government and secretariat. Airship charts the history of these vessels from the continental pioneers of the late nineteenth century to Britains airship stations in the First World War and the building in 19249 of the behemoth R100 and its sister vessel the R101. It studies the crucial role of Count Zeppelin, the development of the Zeppelin airship in Germany as a bomber and reconnaissance craft, and the way the British Admiralty imitated German design. In Britain the airship was characterised by uncertain military involvement and political volatility. It was a time of strife: mass unemployment, the General Strike, in America the Wall Street Crash, all set against the growing shadow of tumult. Across Europe the airship cast its magic. In the United States fleets of airships took to the skies, culminating in two giant vessels, the